Descartes, Rene

"Cogito, ergo sum." ("I think, therefore I am.")

"I think, therefore I am."

"If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things." (07/26,2023)

"Je pense, donc se juis." ("I think, therefore I am.")

"Nothing is more ancient than the truth."

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

René Descartes (born March 31, 1596, La Haye, Touraine, France—died February 11, 1650, Stockholm, Sweden) was a French mathematician, scientist, and philosopher. Because he was one of the first to abandon Scholastic Aristotelianism, because he formulated the first modern version of mind-body dualism, from which stems the mind-body problem, and because he promoted the development of a new science grounded in observation and experiment, he is generally regarded as the founder of modern philosophy. Applying an original system of methodical doubt, he dismissed apparent knowledge derived from authority, the senses, and reason and erected new epistemic foundations on the basis of the intuition that, when he is thinking, he exists; this he expressed in the dictum “I think, therefore I am” (best known in its Latin formulation, “Cogito, ergo sum,” though originally written in French, “Je pense, donc je suis”). He developed a metaphysical dualism that distinguishes radically between mind, the essence of which is thinking, and matter, the essence of which is extension in three dimensions. Descartes’s metaphysics is rationalist, based on the postulation of innate ideas of mind, matter, and God, but his physics and physiology, based on sensory experience, are mechanistic and empiricist.

Early life and education

Although Descartes’s birthplace, La Haye (now Descartes), France, is in Touraine, his family connections lie south, across the Creuse River in Poitou, where his father, Joachim, owned farms and houses in Châtellerault and Poitiers. Because Joachim was a councillor in the Parlement of Brittany in Rennes, Descartes inherited a modest rank of nobility. Descartes’s mother died when he was one year old. His father remarried in Rennes, leaving him in La Haye to be raised first by his maternal grandmother and then by his great-uncle in Châtellerault. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots, and Châtellerault, a Protestant stronghold, was the site of negotiations over the Edict of Nantes (1598), which gave Protestants freedom of worship in France following the intermittent Wars of Religion between Protestant and Catholic forces in France. Descartes returned to Poitou regularly until 1628.

In 1606 Descartes was sent to the Jesuit college at La Flèche, established in 1604 by Henry IV (reigned 1589–1610). At La Flèche, 1,200 young men were trained for careers in military engineering, the judiciary, and government administration. In addition to classical studies, science, mathematics, and metaphysics—Aristotle was taught from Scholastic commentaries—they studied acting, music, poetry, dancing, riding, and fencing. In 1610 Descartes participated in an imposing ceremony in which the heart of Henry IV, whose assassination that year had destroyed the hope of religious tolerance in France and Germany, was placed in the cathedral at La Flèche.

In 1614 Descartes went to Poitiers, where he took a law degree in 1616. At this time, Huguenot Poitiers was in virtual revolt against the young King Louis XIII (reigned 1610–43). Descartes’s father probably expected him to enter Parlement, but the minimum age for doing so was 27, and Descartes was only 20. In 1618 he went to Breda in the Netherlands, where he spent 15 months as an informal student of mathematics and military architecture in the peacetime army of the Protestant stadtholder, Prince Maurice (ruled 1585–1625). In Breda, Descartes was encouraged in his studies of science and mathematics by the physicist Isaac Beeckman (1588–1637), for whom he wrote the Compendium of Music (written 1618, published 1650), his first surviving work.

Descartes spent the period 1619 to 1628 traveling in northern and southern Europe, where, as he later explained, he studied “the book of the world.” While in Bohemia in 1619, he invented analytic geometry, a method of solving geometric problems algebraically and algebraic problems geometrically. He also devised a universal method of deductive reasoning, based on mathematics, that is applicable to all the sciences. This method, which he later formulated in Discourse on Method (1637) and Rules for the Direction of the Mind (written by 1628 but not published until 1701), consists of four rules: (1) accept nothing as true that is not self-evident, (2) divide problems into their simplest parts, (3) solve problems by proceeding from simple to complex, and (4) recheck the reasoning. These rules are a direct application of mathematical procedures. In addition, Descartes insisted that all key notions and the limits of each problem must be clearly defined.

Descartes also investigated reports of esoteric knowledge, such as the claims of the practitioners of theosophy to be able to command nature. Although disappointed with the followers of the Catalan mystic Ramon Llull (1232/33–1315/16) and the German alchemist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535), he was impressed by the German mathematician Johann Faulhaber (1580–1635), a member of the mystical society of the Rosicrucians.

Descartes shared a number of Rosicrucian goals and habits. Like the Rosicrucians, he lived alone and in seclusion, changed his residence often (during his 22 years in the Netherlands, he lived in 18 different places), practiced medicine without charge, attempted to increase human longevity, and took an optimistic view of the capacity of science to improve the human condition.

At the end of his life, he left a chest of personal papers (none of which has survived) with a Rosicrucian physician—his close friend Corneille van Hogelande, who handled his affairs in the Netherlands. Despite these affinities, Descartes rejected the Rosicrucians’ magical and mystical beliefs. For him, this period was a time of hope for a revolution in science. The English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626), in Advancement of Learning (1605), had earlier proposed a new science of observation and experiment to replace the traditional Aristotelian science, as Descartes himself did later.

In 1622 Descartes moved to Paris. There he gambled, rode, fenced, and went to the court, concerts, and the theatre. Among his friends were the poets Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac (1597–1654), who dedicated his Le Socrate chrétien (1652; “Christian Socrates”) to Descartes, and Théophile de Viau (1590–1626), who was burned in effigy and imprisoned in 1623 for writing verses mocking religious themes. Descartes also befriended the mathematician Claude Mydorge (1585–1647) and Father Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), a person of universal learning who corresponded with hundreds of scholars, writers, mathematicians, and scientists and who became Descartes’s main contact with the larger intellectual world. During this time Descartes regularly hid from his friends to work, writing treatises, now lost, on fencing and metals. He acquired a considerable reputation long before he published anything.

At a talk in 1628, Descartes denied the alchemist Chandoux’s claim that probabilities are as good as certainties in science and demonstrated his own method for attaining certainty. The Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (1575–1629)—who had founded the Oratorian teaching congregation in 1611 as a rival to the Jesuits—was present at the talk. Many commentators speculate that Bérulle urged Descartes to write a metaphysics based on the philosophy of St. Augustine as a replacement for Jesuit teaching. Be that as it may, within weeks Descartes left for the Netherlands, which was Protestant, and—taking great precautions to conceal his address—did not return to France for 16 years. Some scholars claim that Descartes adopted Bérulle as director of his conscience, but this is unlikely, given Descartes’s background and beliefs (he came from a Huguenot province, he was not a Catholic enthusiast, he had been accused of being a Rosicrucian, and he advocated religious tolerance and championed the use of reason).

Residence in the Netherlands

Descartes said that he went to the Netherlands to enjoy a greater liberty than was available anywhere else and to avoid the distractions of Paris and friends so that he could have the leisure and solitude to think. (He had inherited enough money and property to live independently.) The Netherlands was a haven of tolerance, where Descartes could be an original, independent thinker without fear of being burned at the stake—as was the Italian philosopher Lucilio Vanini (1585–1619) for proposing natural explanations of miracles—or being drafted into the armies then prosecuting the Catholic Counter-Reformation. In France, by contrast, religious intolerance was mounting. The Jews were expelled in 1615, and the last Protestant stronghold, La Rochelle, was crushed—with Bérulle’s participation—only weeks before Descartes’s departure. In 1624 the French Parlement passed a decree forbidding criticism of Aristotle on pain of death. Although Mersenne and the philosopher Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) did publish attacks on Aristotle without suffering persecution (they were, after all, Catholic priests), those judged to be heretics continued to be burned, and the laity lacked church protection. In addition, Descartes may have felt jeopardized by his friendship with intellectual libertines such as Father Claude Picot (died 1668), a bon vivant known as “the Atheist Priest,” with whom he entrusted his financial affairs in France.

In 1629 Descartes went to the university at Franeker, where he stayed with a Catholic family and wrote the first draft of his Meditations. He matriculated at the University of Leiden in 1630. In 1631 he visited Denmark with the physician and alchemist Étienne de Villebressieu, who invented siege engines, a portable bridge, and a two-wheeled stretcher. The physician Henri Regius (1598–1679), who taught Descartes’s views at the University of Utrecht in 1639, involved Descartes in a fierce controversy with the Calvinist theologian Gisbertus Voetius (1589–1676) that continued for the rest of Descartes’s life. In his Letter to Voetius of 1648, Descartes made a plea for religious tolerance and individual rights. Claiming to write not only for Christians but also for Turks—meaning Muslims, libertines, infidels, deists, and atheists—he argued that, because Protestants and Catholics worship the same God, both can hope for heaven. When the controversy became intense, however, Descartes sought the protection of the French ambassador and of his friend Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), secretary to the stadtholder Prince Frederick Henry (ruled 1625–47).

In 1635 Descartes’s daughter Francine was born to Helena Jans and was baptized in the Reformed Church in Deventer. Although Francine is typically referred to by commentators as Descartes’s “illegitimate” daughter, her baptism is recorded in a register for legitimate births. Her death of scarlet fever at the age of five was the greatest sorrow of Descartes’s life. Referring to her death, Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man.

The World and Discourse on Method

In 1633, just as he was about to publish The World (1664), Descartes learned that the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) had been condemned in Rome for publishing the view that the Earth revolves around the Sun. Because this Copernican position is central to his cosmology and physics, Descartes suppressed The World, hoping that eventually the church would retract its condemnation. Although Descartes feared the church, he also hoped that his physics would one day replace that of Aristotle in church doctrine and be taught in Catholic schools.

Descartes’s Discourse on Method (1637) is one of the first important modern philosophical works not written in Latin. Descartes said that he wrote in French so that all who had good sense, including women, could read his work and learn to think for themselves. He believed that everyone could tell true from false by the natural light of reason. In three essays accompanying the Discourse, he illustrated his method for utilizing reason in the search for truth in the sciences: in Dioptrics he derived the law of refraction, in Meteorology he explained the rainbow, and in Geometry he gave an exposition of his analytic geometry. He also perfected the system invented by François Viète for representing known numerical quantities with a, b, c, …, unknowns with x, y, z, …, and squares, cubes, and other powers with numerical superscripts, as in x2, x3, …, which made algebraic calculations much easier than they had been before.

In the Discourse he also provided a provisional moral code (later presented as final) for use while seeking truth: (1) obey local customs and laws, (2) make decisions on the best evidence and then stick to them firmly as though they were certain, (3) change desires rather than the world, and (4) always seek truth. This code exhibits Descartes’s prudential conservatism, decisiveness, stoicism, and dedication. The Discourse and other works illustrate Descartes’s conception of knowledge as being like a tree in its interconnectedness and in the grounding provided to higher forms of knowledge by lower or more fundamental ones. Thus, for Descartes, metaphysics corresponds to the roots of the tree, physics to the trunk, and medicine, mechanics, and morals to the branches.

Meditations of René Descartes

In 1641 Descartes published the Meditations on First Philosophy, in Which Is Proved the Existence of God and the Immortality of the Soul. Written in Latin and dedicated to the Jesuit professors at the Sorbonne in Paris, the work includes critical responses by several eminent thinkers—collected by Mersenne from the Jansenist philosopher and theologian Antoine Arnauld (1612–94), the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), and the Epicurean atomist Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655)—as well as Descartes’s replies. The second edition (1642) includes a response by the Jesuit priest Pierre Bourdin (1595–1653), who Descartes said was a fool. These objections and replies constitute a landmark of cooperative discussion in philosophy and science at a time when dogmatism was the rule.

The Meditations is characterized by Descartes’s use of methodic doubt, a systematic procedure of rejecting as though false all types of belief in which one has ever been, or could ever be, deceived. His arguments derive from the skepticism of the Greek philosopher Sextus Empiricus (flourished 3rd century ce) as reflected in the work of the essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) and the Catholic theologian Pierre Charron (1541–1603). Thus, Descartes’s apparent knowledge based on authority is set aside, because even experts are sometimes wrong. His beliefs from sensory experience are declared untrustworthy, because such experience is sometimes misleading, as when a square tower appears round from a distance. Even his beliefs about the objects in his immediate vicinity may be mistaken, because, as he notes, he often has dreams about objects that do not exist, and he has no way of knowing with certainty whether he is dreaming or awake. Finally, his apparent knowledge of simple and general truths of reasoning that do not depend on sense experience—such as “2 + 3 = 5” or “a square has four sides”—is also unreliable, because God could have made him in such a way that, for example, he goes wrong every time he counts. As a way of summarizing the universal doubt into which he has fallen, Descartes supposes that an “evil genius of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me.”

Although at this stage there is seemingly no belief about which he cannot entertain doubt, Descartes finds certainty in the intuition that, when he is thinking—even if he is being deceived—he must exist. In the Discourse, Descartes expresses this intuition in the dictum “I think, therefore I am”; but because “therefore” suggests that the intuition is an argument—though it is not—in the Meditations he says merely, “I think, I am” (“Cogito, sum”). The cogito is a logically self-evident truth that also gives intuitively certain knowledge of a particular thing’s existence—that is, one’s self. Nevertheless, it justifies accepting as certain only the existence of the person who thinks it. If all one ever knew for certain was that one exists, and if one adhered to Descartes’s method of doubting all that is uncertain, then one would be reduced to solipsism, the view that nothing exists but one’s self and thoughts. To escape solipsism, Descartes argues that all ideas that are as “clear and distinct” as the cogito must be true, for, if they were not, the cogito also, as a member of the class of clear and distinct ideas, could be doubted. Since “I think, I am” cannot be doubted, all clear and distinct ideas must be true.

On the basis of clear and distinct innate ideas, Descartes then establishes that each mind is a mental substance and each body a part of one material substance. The mind or soul is immortal, because it is unextended and cannot be broken into parts, as can extended bodies. Descartes also advances at least two proofs for the existence of God. The final proof, presented in the Fifth Meditation, begins with the proposition that Descartes has an innate idea of God as a perfect being. It concludes that God necessarily exists, because, if he did not, he would not be perfect. This ontological argument for God’s existence, introduced by the medieval English logician St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033/34–1109), is at the heart of Descartes’s rationalism, for it establishes certain knowledge about an existing thing solely on the basis of reasoning from innate ideas, with no help from sensory experience. Descartes elsewhere argues that, because God is perfect, he does not deceive human beings, and therefore, because God leads humans to believe that the material world exists, it does exist. In this way Descartes claims to establish metaphysical foundations for the existence of his own mind, of God, and of the material world.

The inherent circularity of Descartes’s reasoning was exposed by Arnauld, whose objection has come to be known as the Cartesian Circle. According to Descartes, God’s existence is established by the fact that Descartes has a clear and distinct idea of God; but the truth of Descartes’s clear and distinct ideas are guaranteed by the fact that God exists and is not a deceiver. Thus, in order to show that God exists, Descartes must assume that God exists.

Physics, physiology, and morals

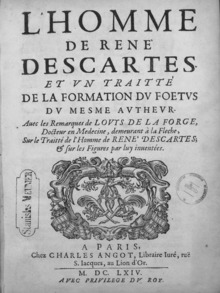

Descartes’s general goal was to help human beings master and possess nature. He provided understanding of the trunk of the tree of knowledge in The World, Dioptrics, Meteorology, and Geometry, and he established its metaphysical roots in the Meditations. He then spent the rest of his life working on the branches of mechanics, medicine, and morals. Mechanics is the basis of his physiology and medicine, which in turn is the basis of his moral psychology. Descartes believed that all material bodies, including the human body, are machines that operate by mechanical principles. In his physiological studies, he dissected animal bodies to show how their parts move. He argued that, because animals have no souls, they do not think or feel; thus, vivisection, which Descartes practiced, is permitted. He also described the circulation of the blood but came to the erroneous conclusion that heat in the heart expands the blood, causing its expulsion into the veins. Descartes’s L’Homme, et un traité de la formation du foetus (Man, and a Treatise on the Formation of the Foetus) was published in 1664.

In 1644 Descartes published Principles of Philosophy, a compilation of his physics and metaphysics. He dedicated this work to Princess Elizabeth (1618–79), daughter of Elizabeth Stuart, titular queen of Bohemia, in correspondence with whom he developed his moral philosophy. According to Descartes, a human being is a union of mind and body, two radically dissimilar substances that interact in the pineal gland. He reasoned that the pineal gland must be the uniting point because it is the only nondouble organ in the brain, and double reports, as from two eyes, must have one place to merge. He argued that each action on a person’s sense organs causes subtle matter to move through tubular nerves to the pineal gland, causing it to vibrate distinctively. These vibrations give rise to emotions and passions and also cause the body to act. Bodily action is thus the final outcome of a reflex arc that begins with external stimuli—as, for example, when a soldier sees the enemy, feels fear, and flees. The mind cannot change bodily reactions directly—for example, it cannot will the body to fight—but by altering mental attitudes, it can change the pineal vibrations from those that cause fear and fleeing to those that cause courage and fighting.

Descartes argued further that human beings can be conditioned by experience to have specific emotional responses. Descartes himself, for example, had been conditioned to be attracted to cross-eyed women because he had loved a cross-eyed playmate as a child. When he remembered this fact, however, he was able to rid himself of his passion. This insight is the basis of Descartes’s defense of free will and of the mind’s ability to control the body. Despite such arguments, in his Passions of the Soul (1649), which he dedicated to Queen Christina of Sweden (reigned 1644–54), Descartes holds that most bodily actions are determined by external material causes.

Descartes’s morality is anti-Jansenist and anti-Calvinist in that he maintains that the grace that is necessary for salvation can be earned and that human beings are virtuous and able to achieve salvation when they do their best to find and act upon the truth. His optimism about the ability of human reason and will to find truth and reach salvation contrasts starkly with the pessimism of the Jansenist apologist and mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623–62), who believed that salvation comes only as a gift of God’s grace. Descartes was correctly accused of holding the view of Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609), an anti-Calvinist Dutch theologian, that salvation depends on free will and good works rather than on grace. Descartes also held that, unless people believe in God and immortality, they will see no reason to be moral.

Free will, according to Descartes, is the sign of God in human nature, and human beings can be praised or blamed according to their use of it. People are good, he believed, only to the extent that they act freely for the good of others; such generosity is the highest virtue. Descartes was Epicurean in his assertion that human passions are good in themselves. He was an extreme moral optimist in his belief that understanding of the good is automatically followed by a desire to do the good. Moreover, because passions are “willings” according to Descartes, to want something is the same as to will it. Descartes was also stoic, however, in his admonition that, rather than change the world, human beings should control their passions.

Although Descartes wrote no political philosophy, he approved of the admonition of Seneca (c. 4 bce–65 ce) to acquiesce in the common order of things. He rejected the recommendation of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) to lie to one’s friends, because friendship is sacred and life’s greatest joy. Human beings cannot exist alone but must be parts of social groups, such as nations and families, and it is better to do good for the group than for oneself.

Descartes had been a puny child with a weak chest and was not expected to live. He therefore watched his health carefully, becoming a virtual vegetarian. In 1639 he bragged that he had not been sick for 19 years and that he expected to live to 100. He told Princess Elizabeth to think of life as a comedy; bad thoughts cause bad dreams and bodily disorders. Because there is always more good than evil in life, he said, one can always be content, no matter how bad things seem. Elizabeth, inextricably involved in messy court and family affairs, was not consoled.

In his later years Descartes said that he had once hoped to learn to prolong life to a century or more, but he then saw that, to achieve that goal, the work of many generations would be required; he himself had not even learned to prevent a fever. Thus, he said, instead of continuing to hope for long life, he had found an easier way, namely to love life and not to fear death. It is easy, he claimed, for a true philosopher to die tranquilly.

Final years and heritage of René Descartes

In 1644, 1647, and 1648, after 16 years in the Netherlands, Descartes returned to France for brief visits on financial business and to oversee the translation into French of the Principles, the Meditations, and the Objections and Replies. (The translators were, respectively, Picot, Charles d’Albert, duke de Luynes, and Claude Clerselier.) In 1647 he also met with Gassendi and Hobbes, and he suggested to Pascal the famous experiment of taking a barometer up Mount Puy-de-Dôme to determine the influence of the weight of the air. Picot returned with Descartes to the Netherlands for the winter of 1647–48. During Descartes’s final stay in Paris in 1648, the French nobility revolted against the crown in a series of wars known as the Fronde. Descartes left precipitously on August 17, 1648, only days before the death of his old friend Mersenne.

Clerselier’s brother-in-law, Hector Pierre Chanut, who was French resident in Sweden and later ambassador, helped to procure a pension for Descartes from Louis XIV, though it was never paid. Later, Chanut engineered an invitation for Descartes to the court of Queen Christina, who by the close of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) had become one of the most important and powerful monarchs in Europe. Descartes went reluctantly, arriving early in October 1649. He may have gone because he needed patronage; the Fronde seemed to have destroyed his chances in Paris, and the Calvinist theologians were harassing him in the Netherlands.

In Sweden—where, Descartes said, in winter men’s thoughts freeze like the water—the 22-year-old Christina perversely made the 53-year-old Descartes rise before 5:00 am to give her philosophy lessons, even though she knew of his habit of lying in bed until 11 o’clock in the morning. She also is said to have ordered him to write the verses of a ballet, The Birth of Peace (1649), to celebrate her role in the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years’ War. The verses in fact were not written by Descartes, though he did write the statutes for a Swedish Academy of Arts and Sciences. While delivering these statutes to the queen at 5:00 am on February 1, 1650, he caught a chill, and he soon developed pneumonia. He died in Stockholm on February 11. Many pious last words have been attributed to him, but the most trustworthy report is that of his German valet, who said that Descartes was in a coma and died without saying anything at all.

Descartes’s papers came into the possession of Claude Clerselier, a pious Catholic, who began the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding to, and selectively publishing his letters. This cosmetic work culminated in 1691 in the massive biography by Father Adrien Baillet, who was at work on a 17-volume Lives of the Saints. Even during Descartes’s lifetime there were questions about whether he was a Catholic apologist, primarily concerned with supporting Christian doctrine, or an atheist, concerned only with protecting himself with pious sentiments while establishing a deterministic, mechanistic, and materialistic physics.

These questions remain difficult to answer, not least because all the papers, letters, and manuscripts available to Clerselier and Baillet are now lost. In 1667 the Roman Catholic Church made its own decision by putting Descartes’s works on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Latin: “Index of Prohibited Books”) on the very day his bones were ceremoniously placed in Sainte-Geneviève-du-Mont in Paris. During his lifetime, Protestant ministers in the Netherlands called Descartes a Jesuit and a papist—which is to say an atheist. He retorted that they were intolerant, ignorant bigots. Up to about 1930, a majority of scholars, many of whom were religious, believed that Descartes’s major concerns were metaphysical and religious. By the late 20th century, however, numerous commentators had come to believe that Descartes was a Catholic in the same way he was a Frenchman and a royalist—that is, by birth and by convention.

Descartes himself said that good sense is destroyed when one thinks too much of God. He once told a German protégée, Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–78), who was known as a painter and a poet, that she was wasting her intellect studying Hebrew and theology. He also was perfectly aware of—though he tried to conceal—the atheistic potential of his materialist physics and physiology. Descartes seemed indifferent to the emotional depths of religion. Whereas Pascal trembled when he looked into the infinite universe and perceived the puniness and misery of humanity, Descartes exulted in the power of human reason to understand the cosmos and to promote happiness, and he rejected the view that human beings are essentially miserable and sinful. He held that it is impertinent to pray to God to change things. Instead, when we cannot change the world, we must change ourselves.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

René Descartes (/deɪˈkɑːrt/ day-KART or UK: /ˈdeɪkɑːrt/ DAY-kart; French: [ʁəne dekaʁt] ; [note 3][11] 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650)[12][13]: 58 was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathematics was paramount to his method of inquiry, and he connected the previously separate fields of geometry and algebra into analytic geometry. Descartes spent much of his working life in the Dutch Republic, initially serving the Dutch States Army, and later becoming a central intellectual of the Dutch Golden Age.[14] Although he served a Protestant state and was later counted as a deist by critics, Descartes was Roman Catholic.[15][16]

Many elements of Descartes' philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differed from the schools on two major points. First, he rejected the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejected any appeal to final ends, divine or natural, in explaining natural phenomena.[17] In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God's act of creation. Refusing to accept the authority of previous philosophers, Descartes frequently set his views apart from the philosophers who preceded him. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic "as if no one had written on these matters before." His best known philosophical statement is "cogito, ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am"; French: Je pense, donc je suis), found in Discourse on the Method (1637, in French and Latin, 1644) and Principles of Philosophy (1644, in Latin, 1647 in French).[note 4] The statement has either been interpreted as a logical syllogism or as an intuitive thought.[18]

Descartes has often been called the father of modern philosophy, and is largely seen as responsible for the increased attention given to epistemology in the 17th century.[19][note 5] He laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Spinoza and Leibniz, and was later opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. The rise of early modern rationalism—as a systematic school of philosophy in its own right for the first time in history—exerted an influence on modern Western thought in general, with the birth of two rationalistic philosophical systems of Descartes (Cartesianism) and Spinoza (Spinozism). It was the 17th-century arch-rationalists like Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz who have given the "Age of Reason" its name and place in history. Leibniz, Spinoza,[20] and Descartes were all well-versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, with Descartes and Leibniz additionally contributing to a variety of scientific disciplines.[21]

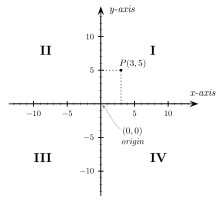

Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes' influence in mathematics is equally apparent, being the namesake of the Cartesian coordinate system. He is credited as the father of analytic geometry—used in the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution.

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]

René Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, Province of Touraine (now Descartes, Indre-et-Loire), France, on 31 March 1596.[22] In May 1597, his mother Jeanne Brochard, died a few days after giving birth to a still-born child.[23][22] Descartes' father, Joachim, was a member of the Parlement of Rennes at Rennes.[24]: 22 René lived with his grandmother and with his great-uncle. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots.[25] In 1607, late because of his fragile health, he entered the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche,[26][27] where he was introduced to mathematics and physics, including Galileo's work.[28][29] While there, Descartes first encountered hermetic mysticism. After graduation in 1614, he studied for two years (1615–16) at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and Licence in canon and civil law in 1616,[28] in accordance with his father's wishes that he should become a lawyer.[30] From there, he moved to Paris.

In Discourse on the Method, Descartes recalls:[31]: 20–21

Army service

[edit]In accordance with his ambition to become a professional military officer in 1618, Descartes joined, as a mercenary, the Protestant Dutch States Army in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau,[28] and undertook a formal study of military engineering, as established by Simon Stevin.[32] Descartes, therefore, received much encouragement in Breda to advance his knowledge of mathematics.[28] In this way, he became acquainted with Isaac Beeckman,[28] the principal of a Dordrecht school, for whom he wrote the Compendium of Music (written 1618, published 1650).[33]

While in the service of the Catholic Duke Maximilian of Bavaria from 1619,[34] Descartes was present at the Battle of the White Mountain near Prague, in November 1620.[35][36]

According to Adrien Baillet, on the night of 10–11 November 1619 (St. Martin's Day), while stationed in Neuburg an der Donau, Descartes shut himself in a room with an "oven" (probably a cocklestove)[37] to escape the cold. While within, he had three dreams,[38] and believed that a divine spirit revealed to him a new philosophy. However, it is speculated that what Descartes considered to be his second dream was actually an episode of exploding head syndrome.[39] Upon exiting, he had formulated analytic geometry and the idea of applying the mathematical method to philosophy. He concluded from these visions that the pursuit of science would prove to be, for him, the pursuit of true wisdom and a central part of his life's work.[40][41] Descartes also saw very clearly that all truths were linked with one another, so that finding a fundamental truth and proceeding with logic would open the way to all science. Descartes discovered this basic truth quite soon: his famous "I think, therefore I am."[42]

Career

[edit]France

[edit]In 1620, Descartes left the army. He visited Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, then visited various countries before returning to France, and during the next few years, he spent time in Paris. It was there that he composed his first essay on method: Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind).[42] He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property to invest in bonds, which provided a comfortable income for the rest of his life.[43][44]: 94 Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627 as an observer.[44]: 128 There, he was interested in the physical properties of the great dike that Richelieu was building and studied mathematically everything he saw during the siege. He also met French mathematician Girard Desargues.[45] In the autumn of that year, in the residence of the papal nuncio Guidi di Bagno, where he came with Mersenne and many other scholars to listen to a lecture given by the alchemist, Nicolas de Villiers, Sieur de Chandoux, on the principles of a supposed new philosophy,[46] Cardinal Bérulle urged him to write an exposition of his new philosophy in some location beyond the reach of the Inquisition.[47]

Netherlands

[edit]

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628.[38] In April 1629, he joined the University of Franeker, studying under Adriaan Metius, either living with a Catholic family or renting the Sjaerdemaslot. The next year, under the name "Poitevin", he enrolled at Leiden University, which at the time was a Protestant University.[48] He studied both mathematics with Jacobus Golius, who confronted him with Pappus's hexagon theorem, and astronomy with Martin Hortensius.[49] In October 1630, he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, who was born in 1635 in Deventer. She was baptized a Protestant[50][51] and died of scarlet fever at the age of 5.

Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes did not deprecate the passions but rather defended them;[52] he wept upon Francine's death in 1640.[53] According to a recent biography by Jason Porterfield, "Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man."[54] Russell Shorto speculates that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes' work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.[55]

Despite frequent moves,[note 6] he wrote all of his major work during his 20-plus years in the Netherlands, initiating a revolution in mathematics and philosophy.[note 7] In 1633, Galileo was condemned by the Italian Inquisition, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish Treatise on the World, his work of the previous four years. Nevertheless, in 1637, he published parts of this work in three essays:[56] "Les Météores" (The Meteors), "La Dioptrique" (Dioptrics) and La Géométrie (Geometry), preceded by an introduction, his famous Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method).[56] In it, Descartes lays out four rules of thought, meant to ensure that our knowledge rests upon a firm foundation:[57]

In La Géométrie, Descartes exploited the discoveries he made with Pierre de Fermat. This later became known as Cartesian Geometry.[58]

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641, he published a metaphysics treatise, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed in 1644 by Principia Philosophiae (Principles of Philosophy), a kind of synthesis of the Discourse on the Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes was obliged to flee to the Hague, settling in Egmond-Binnen.

Between 1643 and 1649 Descartes lived with his girlfriend at Egmond-Binnen in an inn.[59] Descartes became friendly with Anthony Studler van Zurck, lord of Bergen and participated in the design of his mansion and estate.[60][61][62] He also met Dirck Rembrantsz van Nierop, a mathematician and surveyor.[63] He was so impressed by Van Nierop's knowledge that he even brought him to the attention of Constantijn Huygens and Frans van Schooten.[64]

Christia Mercer suggested that Descartes may have been influenced by Spanish author and Roman Catholic nun Teresa of Ávila, who, fifty years earlier, published The Interior Castle, concerning the role of philosophical reflection in intellectual growth.[65][66]

Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a six-year correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, devoted mainly to moral and psychological subjects.[67] Connected with this correspondence, in 1649 he published Les Passions de l'âme (The Passions of the Soul), which he dedicated to the Princess. A French translation of Principia Philosophiae, prepared by Abbot Claude Picot, was published in 1647. This edition was also dedicated to Princess Elisabeth. In the preface to the French edition, Descartes praised true philosophy as a means to attain wisdom. He identifies four ordinary sources to reach wisdom and finally says that there is a fifth, better and more secure, consisting in the search for first causes.[68]

Sweden

[edit]

By 1649, Descartes had become one of Europe's most famous philosophers and scientists.[56] That year, Queen Christina of Sweden invited him to her court to organize a new scientific academy and tutor her in his ideas about love.[69] Descartes accepted, and moved to the Swedish Empire in the middle of winter.[70] Christina was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish The Passions of the Soul.[71]

He was a guest at the house of Pierre Chanut, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Castle Tre Kronor in Stockholm. There, Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian mercury barometer.[69] Challenging Blaise Pascal, Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure could be used in forecasting the weather.[72]

Death

[edit]Descartes arranged to give lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week at 5 am, in her cold and draughty castle. However, by 15 January 1650 the Queen had actually met with Descartes only four or five times.[69] It soon became clear they did not like each other; she did not care for his mechanical philosophy, nor did he share her interest in Ancient Greek language and literature.[69] On 1 February 1650, he contracted pneumonia and died on 11 February at Chanut.[73]

The cause of death was pneumonia according to Chanut, but peripneumonia according to Christina's physician Johann van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him.[75] (The winter seems to have been mild,[76] except for the second half of January which was harsh as described by Descartes himself; however, "this remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather.")[71]

E. Pies has questioned this account, based on a letter by the Doctor van Wullen; however, Descartes had refused his treatment, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.[77] In a 2009 book, German philosopher Theodor Ebert argues that Descartes was poisoned by Jacques Viogué, a Catholic missionary who opposed his religious views.[78][79] As evidence, Ebert suggests that Catherine Descartes, the niece of René Descartes, made a veiled reference to the act of poisoning when her uncle was administered "communion" two days before his death, in her Report on the Death of M. Descartes, the Philosopher (1693).[80]

As a Catholic[81][82][83] in a Protestant nation, he was interred in the churchyard of what was to become Adolf Fredrik Church in Stockholm, where mainly orphans had been buried. His manuscripts came into the possession of Claude Clerselier, Chanut's brother-in-law, and "a devout Catholic who has begun the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding and publishing his letters selectively."[84][85]: 137–154 In 1663, the Pope placed Descartes' works on the Index of Prohibited Books. In 1666, sixteen years after his death, his remains were taken to France and buried in Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. In 1671, Louis XIV prohibited all lectures in Cartesianism. Although the National Convention in 1792 had planned to transfer his remains to the Panthéon, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819, missing a finger and the skull.[note 8] His skull is in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris.[86]

Philosophical work

[edit]

In his Discourse on the Method, he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as methodological skepticism or Cartesian doubt: he rejects any ideas that can be doubted and then re-establishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge.[87] Descartes built his ideas from scratch which he does in The Meditations on First Philosophy. He relates this to architecture: the top soil is taken away to create a new building or structure. Descartes calls his doubt the soil and new knowledge the buildings. To Descartes, Aristotle's foundationalism is incomplete and his method of doubt enhances foundationalism.[88]

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single first principle: he thinks. This is expressed in the Latin phrase in the Discourse on Method "Cogito, ergo sum" (English: "I think, therefore I am").[89] Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting; therefore, the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. "The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist."[90] These two first principles—I think and I exist—were later confirmed by Descartes' clear and distinct perception (delineated in his Third Meditation from The Meditations): as he clearly and distinctly perceives these two principles, Descartes reasoned, ensures their indubitability.

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines "thought" (cogitatio) as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it". Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious.[91] He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams, and that one's mind cannot have been "hijacked" by an evil demon placing an illusory external world before one's senses.[88]

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and, instead, admitting only deduction as a method.[93]

Mind–body dualism

[edit]

Descartes, influenced by the automatons on display at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye near Paris, investigated the connection between mind and body, and how they interact.[94] His main influences for dualism were theology and physics.[95] The theory on the dualism of mind and body is Descartes' signature doctrine and permeates other theories he advanced. Known as Cartesian dualism (or mind–body dualism), his theory on the separation between the mind and the body went on to influence subsequent Western philosophies.[96] In Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes attempted to demonstrate the existence of God and the distinction between the human soul and the body. Humans are a union of mind and body;[97] thus Descartes' dualism embraced the idea that mind and body are distinct but closely joined. While many contemporary readers of Descartes found the distinction between mind and body difficult to grasp, he thought it was entirely straightforward. Descartes employed the concept of modes, which are the ways in which substances exist. In Principles of Philosophy, Descartes explained, "we can clearly perceive a substance apart from the mode which we say differs from it, whereas we cannot, conversely, understand the mode apart from the substance". To perceive a mode apart from its substance requires an intellectual abstraction,[98] which Descartes explained as follows:

According to Descartes, two substances are really distinct when each of them can exist apart from the other. Thus, Descartes reasoned that God is distinct from humans, and the body and mind of a human are also distinct from one another.[99] He argued that the great differences between body (an extended thing) and mind (an un-extended, immaterial thing) make the two ontologically distinct. According to Descartes' indivisibility argument, the mind is utterly indivisible: because "when I consider the mind, or myself in so far as I am merely a thinking thing, I am unable to distinguish any part within myself; I understand myself to be something quite single and complete."[100]

Moreover, in The Meditations, Descartes discusses a piece of wax and exposes the single most characteristic doctrine of Cartesian dualism: that the universe contained two radically different kinds of substances—the mind or soul defined as thinking, and the body defined as matter and unthinking.[101] The Aristotelian philosophy of Descartes' days held that the universe was inherently purposeful or teleological. Everything that happened, be it the motion of the stars or the growth of a tree, was supposedly explainable by a certain purpose, goal or end that worked its way out within nature. Aristotle called this the "final cause", and these final causes were indispensable for explaining the ways nature operated. Descartes' theory of dualism supports the distinction between traditional Aristotelian science and the new science of Kepler and Galileo, which denied the role of a divine power and "final causes" in its attempts to explain nature. Descartes' dualism provided the philosophical rationale for the latter by expelling the final cause from the physical universe (or res extensa) in favor of the mind (or res cogitans). Therefore, while Cartesian dualism paved the way for modern physics, it also held the door open for religious beliefs about the immortality of the soul.[102]

Descartes' dualism of mind and matter implied a concept of human beings. A human was, according to Descartes, a composite entity of mind and body. Descartes gave priority to the mind and argued that the mind could exist without the body, but the body could not exist without the mind. In The Meditations, Descartes even argues that while the mind is a substance, the body is composed only of "accidents".[103] But he did argue that mind and body are closely joined:[104]

Descartes' discussion on embodiment raised one of the most perplexing problems of his dualism philosophy: What exactly is the relationship of union between the mind and the body of a person?[104] Therefore, Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the mind–body problem for many years after Descartes' death.[105] Descartes was also a rationalist and believed in the power of innate ideas.[106] Descartes argued the theory of innate knowledge and that all humans were born with knowledge through the higher power of God. It was this theory of innate knowledge that was later combated by philosopher John Locke (1632–1704), an empiricist.[107] Empiricism holds that all knowledge is acquired through experience.

Physiology and psychology

[edit]In The Passions of the Soul, published in 1649,[108] Descartes discussed the common contemporary belief that the human body contained animal spirits. These animal spirits were believed to be light and roaming fluids circulating rapidly around the nervous system between the brain and the muscles. These animal spirits were believed to affect the human soul, or passions of the soul. Descartes distinguished six basic passions: wonder, love, hatred, desire, joy and sadness. All of these passions, he argued, represented different combinations of the original spirit, and influenced the soul to will or want certain actions. He argued, for example, that fear is a passion that moves the soul to generate a response in the body. In line with his dualist teachings on the separation between the soul and the body, he hypothesized that some part of the brain served as a connector between the soul and the body and singled out the pineal gland as connector.[109] Descartes argued that signals passed from the ear and the eye to the pineal gland, through animal spirits. Thus different motions in the gland cause various animal spirits. He argued that these motions in the pineal gland are based on God's will and that humans are supposed to want and like things that are useful to them. But he also argued that the animal spirits that moved around the body could distort the commands from the pineal gland, thus humans had to learn how to control their passions.[110]

Descartes advanced a theory on automatic bodily reactions to external events, which influenced 19th-century reflex theory. He argued that external motions, such as touch and sound, reach the endings of the nerves and affect the animal spirits. For example, heat from fire affects a spot on the skin and sets in motion a chain of reactions, with the animal spirits reaching the brain through the central nervous system, and in turn, animal spirits are sent back to the muscles to move the hand away from the fire.[110] Through this chain of reactions, the automatic reactions of the body do not require a thought process.[106]

Above all, he was among the first scientists who believed that the soul should be subject to scientific investigation. He challenged the views of his contemporaries that the soul was divine, thus religious authorities regarded his books as dangerous.[111] Descartes' writings went on to form the basis for theories on emotions and how cognitive evaluations were translated into affective processes. Descartes believed the brain resembled a working machine and that mathematics, and mechanics could explain complicated processes in it.[112] In the 20th century, Alan Turing advanced computer science based on mathematical biology as inspired by Descartes. His theories on reflexes also served as the foundation for advanced physiological theories, more than 200 years after his death. The physiologist Ivan Pavlov was a great admirer of Descartes.[113]

On animals

[edit]Descartes denied that animals had reason or intelligence.[114] He argued that animals did not lack sensations or perceptions, but these could be explained mechanistically.[115] Whereas humans had a soul, or mind, and were able to feel pain and anxiety, animals by virtue of not having a soul could not feel pain or anxiety. If animals showed signs of distress then this was to protect the body from damage, but the innate state needed for them to suffer was absent.[116] Although Descartes's views were not universally accepted, they became prominent in Europe and North America, allowing humans to treat animals with impunity. The view that animals were quite separate from humanity and merely machines allowed for the maltreatment of animals, and was sanctioned in law and societal norms until the middle of the 19th century.[117]: 180–214 The publications of Charles Darwin would eventually erode the Cartesian view of animals.[118]: 37 Darwin argued that the continuity between humans and other species suggested the possibility of animal suffering.[119]: 177

Moral philosophy

[edit]For Descartes, ethics was a science, the highest and most perfect of them. Like the rest of the sciences, ethics had its roots in metaphysics.[93] In this way, he argues for the existence of God, investigates the place of man in nature, formulates the theory of mind–body dualism, and defends free will. However, as he was a convinced rationalist, Descartes clearly states that reason is sufficient in the search for the goods that individuals should seek, and virtue consists in the correct reasoning that should guide their actions. Nevertheless, the quality of this reasoning depends on knowledge and mental condition. For this reason, he said that a complete moral philosophy should include the study of the body.[120]: 189 He discussed this subject in the correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, and as a result wrote his work The Passions of the Soul, that contains a study of the psychosomatic processes and reactions in man, with an emphasis on emotions or passions.[121] His works about human passion and emotion would be the basis for the philosophy of his followers (see Cartesianism), and would have a lasting impact on ideas concerning what literature and art should be, specifically how it should invoke emotion.[122]

Descartes and Zeno both identified sovereign goods with virtue. For Epicurus, the sovereign good was pleasure, and Descartes says that, in fact, this is not in contradiction with Zeno's teaching, because virtue produces a spiritual pleasure that is better than bodily pleasure. Regarding Aristotle's opinion that happiness (eudaimonia) depends on both moral virtue and also on the goods of fortune such as a moderate degree of wealth, Descartes does not deny that fortunes contributes to happiness, but remarks that they are in great proportion outside one's own control, whereas one's mind is under one's complete control.[121] The moral writings of Descartes came at the last part of his life, but earlier, in his Discourse on the Method, he adopted three maxims to be able to act while he put all his ideas into doubt. Those maxims are known as his "Provisional Morals".

Religion

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

In the third and fifth Meditation, Descartes offers proofs of a benevolent God (the trademark argument and the ontological argument respectively). Descartes has faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, since he believed that God provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, Descartes finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. Regarding epistemology, therefore, Descartes can be said to have contributed such ideas as a conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge. Descartes, however, was very much aware that experimentation was necessary to verify and validate theories.[93]

Descartes invokes his causal adequacy principle[123] to support his trademark argument for the existence of God, quoting Lucretius in defence: "Ex nihilo nihil fit", meaning "Nothing comes from nothing" (Lucretius).[124] Oxford Reference summarises the argument, as follows, "that our idea of perfection is related to its perfect origin (God), just as a stamp or trademark is left in an article of workmanship by its maker."[125] In the fifth Meditation, Descartes presents a version of the ontological argument which is founded on the possibility of thinking the "idea of a being that is supremely perfect and infinite," and suggests that "of all the ideas that are in me, the idea that I have of God is the most true, the most clear and distinct."[126]

Descartes considered himself to be a devout Catholic,[81][82][83] and one of the purposes of the Meditations was to defend the Catholic faith. His attempt to ground theological beliefs on reason encountered intense opposition in his time. Pascal regarded Descartes' views as a rationalist and mechanist, and accused him of deism: "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God," while a powerful contemporary, Martin Schoock, accused him of atheist beliefs, though Descartes had provided an explicit critique of atheism in his Meditations. The Catholic Church prohibited his books in 1663.[127][128][129]: 274

Descartes also wrote a response to external world skepticism. Through this method of skepticism, he does not doubt for the sake of doubting but to achieve concrete and reliable information. In other words, certainty. He argues that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, and are not willed by him. They are external to his senses, and according to Descartes, this is evidence of the existence of something outside of his mind, and thus, an external world. Descartes goes on to argue that the things in the external world are material by arguing that God would not deceive him as to the ideas that are being transmitted, and that God has given him the "propensity" to believe that such ideas are caused by material things. Descartes also believes a substance is something that does not need any assistance to function or exist. Descartes further explains how only God can be a true "substance". But minds are substances, meaning they need only God for it to function. The mind is a thinking substance. The means for a thinking substance stem from ideas.[130]

Descartes steered clear of theological questions, restricting his attention to showing that there is no incompatibility between his metaphysics and theological orthodoxy. He avoided trying to demonstrate theological dogmas metaphysically. When challenged that he had not established the immortality of the soul merely in showing that the soul and the body are distinct substances, he replied, "I do not take it upon myself to try to use the power of human reason to settle any of those matters which depend on the free will of God."[131]

Mathematics

[edit]x for unknown; exponential notation

[edit]Descartes "invented the convention of representing unknowns in equations by x, y, and z, and knowns by a, b, and c". He also "pioneered the standard notation" that uses superscripts to show the powers or exponents; for example, the 2 used in x2 to indicate x squared.[132][133]: 19

Analytic geometry

[edit]

One of Descartes' most enduring legacies was his development of Cartesian or analytic geometry, which uses algebra to describe geometry; the Cartesian coordinate system is named after him. He was first to assign a fundamental place for algebra in the system of knowledge, using it as a method to automate or mechanize reasoning, particularly about abstract, unknown quantities.[134]: 91–114 European mathematicians had previously viewed geometry as a more fundamental form of mathematics, serving as the foundation of algebra. Algebraic rules were given geometric proofs by mathematicians such as Pacioli, Cardano, Tartaglia and Ferrari. Equations of degree higher than the third were regarded as unreal, because a three-dimensional form, such as a cube, occupied the largest dimension of reality. Descartes professed that the abstract quantity a2 could represent length as well as an area. This was in opposition to the teachings of mathematicians such as François Viète, who insisted that a second power must represent an area. Although Descartes did not pursue the subject, he preceded Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in envisioning a more general science of algebra or "universal mathematics", as a precursor to symbolic logic, that could encompass logical principles and methods symbolically, and mechanize general reasoning.[135]: 280–281

Influence on Newton's mathematics

[edit]Current popular opinion holds that Descartes had the most influence of anyone on the young Isaac Newton, and this is arguably one of his most important contributions. Descartes' influence extended not directly from his original French edition of La Géométrie, however, but rather from Frans van Schooten's expanded second Latin edition of the work.[136]: 100 Newton continued Descartes' work on cubic equations, which freed the subject from fetters of the Greek perspectives. The most important concept was his very modern treatment of single variables.[137]: 109–129

The basis of calculus

[edit]Descartes' work provided the basis for the calculus developed by Leibniz and Newton, who applied the infinitesimal calculus to the tangent line problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics.[138] His rule of signs is also a commonly used method to determine the number of positive and negative roots of a polynomial.

Physics

[edit]Philosophy, metaphysics, and physics

[edit]Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences.[139] For him, philosophy was a thinking system that embodied all knowledge, as he related in a letter to a French translator:[93]

Mechanics

[edit]Mechanical philosophy

[edit]The beginning to Descartes' interest in physics is accredited to the amateur scientist and mathematician Isaac Beeckman, whom he met in 1618, and who was at the forefront of a new school of thought known as mechanical philosophy. With this foundation of reasoning, Descartes formulated many of his theories on mechanical and geometric physics.[140] It is said that they met when both were looking at a placard that was set up in the Breda marketplace, detailing a mathematical problem to be solved. Descartes asked Beeckman to translate the problem from Dutch to French.[141] In their following meetings Beeckman interested Descartes in his corpuscularian approach to mechanical theory, and convinced him to devote his studies to a mathematical approach to nature.[142][141] In 1628, Beeckman also introduced him to many of Galileo's ideas.[142] Together, they worked on free fall, catenaries, conic sections, and fluid statics. Both believed that it was necessary to create a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics.[42]

Anticipating the concept of work

[edit]Although the concept of work (in physics) was not formally used until 1826, similar concepts existed before then.[143] In 1637, Descartes wrote:[144]

Conservation of motion

[edit]In Principles of Philosophy (Principia Philosophiae) from 1644 Descartes outlined his views on the universe. In it he describes his three laws of motion.[145] (Newton's own laws of motion would later be modeled on Descartes' exposition.)[140] Descartes defined "quantity of motion" (Latin: quantitas motus) as the product of size and speed,[146] and claimed that the total quantity of motion in the universe is conserved.[146]

Descartes had discovered an early form of the law of conservation of momentum.[147] He envisioned quantity of motion as pertaining to motion in a straight line, as opposed to perfect circular motion, as Galileo had envisioned it.[140][147] Descartes' discovery should not be seen as the modern law of conservation of momentum, since it had no concept of mass as distinct from weight or size, and since he believed that it is speed rather than velocity that is conserved.[148][149][150]

Planetary motion

[edit]Descartes' vortex theory of planetary motion was later rejected by Newton in favor of his law of universal gravitation, and most of the second book of Newton's Principia is devoted to his counterargument.

Optics

[edit]Descartes also made contributions to the field of optics. He showed by using geometric construction and the law of refraction (also known as Descartes' law, or more commonly Snell's law outside France) that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42 degrees (i.e., the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow's centre is 42°).[151] He also independently discovered the law of reflection, and his essay on optics was the first published mention of this law.[152]

Meteorology

[edit]Within Discourse on the Method, there is an appendix in which Descartes discusses his theories on Meteorology known as Les Météores. He first proposed the idea that the elements were made up of small particles that join together imperfectly, thus leaving small spaces in between. These spaces were then filled with smaller much quicker "subtile matter".[153] These particles were different based on what element they constructed, for example, Descartes believed that particles of water were "like little eels, which, though they join and twist around each other, do not, for all that, ever knot or hook together in such a way that they cannot easily be separated."[153] In contrast, the particles that made up the more solid material, were constructed in a way that generated irregular shapes. The size of the particle also matters; if the particle was smaller, not only was it faster and constantly moving, it was more easily agitated by the larger particles, which were slow but had more force. The different qualities, such as combinations and shapes, gave rise to different secondary qualities of materials, such as temperature.[154] This first idea is the basis for the rest of Descartes' theory on Meteorology.

While rejecting most of Aristotle's theories on Meteorology, he still kept some of the terminology that Aristotle used such as vapors and exhalations. These "vapors" would be drawn into the sky by the sun from "terrestrial substances" and would generate wind.[153] Descartes also theorized that falling clouds would displace the air below them, also generating wind. Falling clouds could also generate thunder. He theorized that when a cloud rests above another cloud and the air around the top cloud is hot, it condenses the vapor around the top cloud, and causes the particles to fall. When the particles falling from the top cloud collided with the bottom cloud's particles it would create thunder.[154] He compared his theory on thunder to his theory on avalanches. Descartes believed that the booming sound that avalanches created, was due to snow that was heated, and therefore heavier, falling onto the snow that was below it.[154] This theory was supported by experience "It follows that one can understand why it thunders more rarely in winter than in summer; for then not enough heat reaches the highest clouds, in order to break them up."[154]

Another theory that Descartes had was on the production of lightning. Descartes believed that lightning was caused by exhalations trapped between the two colliding clouds. He believed that in order to make these exhalations viable to produce lightning, they had to be made "fine and inflammable" by hot and dry weather.[154] Whenever the clouds would collide, it would cause them to ignite, creating lightning; if the cloud above was heavier than the bottom cloud, it would also produce thunder.

Descartes also believed that clouds were made up of drops of water and ice, and believed that rain would fall whenever the air could no longer support them. It would fall as snow if the air was not warm enough to melt the raindrops. And hail was when the cloud drops would melt, and then freeze again because cold air would refreeze them.[153][154]

Descartes did not use mathematics or instruments (as there were not any at the time) to back up his theories on Meteorology and instead used qualitative reasoning in order to deduce his hypothesis.[153]

Historical impact

[edit]Emancipation from Church doctrine

[edit]

Descartes has often been dubbed the father of modern Western philosophy, the thinker whose approaches has profoundly changed the course of Western philosophy and set the basis for modernity.[19][155] The first two of his Meditations on First Philosophy, those that formulate the famous methodic doubt, represent the portion of Descartes' writings that most influenced modern thinking.[156] It has been argued that Descartes himself did not realize the extent of this revolutionary move.[157] In shifting the debate from "what is true" to "of what can I be certain?", Descartes arguably shifted the authoritative guarantor of truth from God to humanity (even though Descartes himself claimed he received his visions from God)—while the traditional concept of "truth" implies an external authority, "certainty" instead relies on the judgment of the individual.

In an anthropocentric revolution, the human being is now raised to the level of a subject, an agent, an emancipated being equipped with autonomous reason. This was a revolutionary step that established the basis of modernity, the repercussions of which are still being felt: the emancipation of humanity from Christian revelational truth and Church doctrine; humanity making its own law and taking its own stand.[158][159][160] In modernity, the guarantor of truth is not God anymore but human beings, each of whom is a "self-conscious shaper and guarantor" of their own reality.[161][162] In that way, each person is turned into a reasoning adult, a subject and agent,[161] as opposed to a child obedient to God. This change in perspective was characteristic of the shift from the Christian medieval period to the modern period, a shift that had been anticipated in other fields, and which was now being formulated in the field of philosophy by Descartes.[161][163]

This anthropocentric perspective of Descartes' work, establishing human reason as autonomous, provided the basis for the Enlightenment's emancipation from God and the Church. According to Martin Heidegger, the perspective of Descartes' work also provided the basis for all subsequent anthropology.[164] Descartes' philosophical revolution is sometimes said to have sparked modern anthropocentrism and subjectivism.[19][165][166][167]

Contemporary reception

[edit]In commercial terms, The Discourse appeared during Descartes' lifetime in a single edition of 500 copies, 200 of which were set aside for the author. Sharing a similar fate was the only French edition of The Meditations, which had not managed to sell out by the time of Descartes' death. A concomitant Latin edition of the latter was, however, eagerly sought out by Europe's scholarly community and proved a commercial success for Descartes.[168]: xliii–xliv

Although Descartes was well known in academic circles towards the end of his life, the teaching of his works in schools was controversial. Henri de Roy (Henricus Regius, 1598–1679), Professor of Medicine at the University of Utrecht, was condemned by the Rector of the university, Gijsbert Voet (Voetius), for teaching Descartes' physics.[169]

According to philosophy professor John Cottingham, Descartes's Meditations on First Philosophy is considered to be "one of the key texts of Western philosophy". Cottingham said that the Meditations is the "most widely studied of all Descartes' writings".[170]: 50

According to Anthony Gottlieb, a former senior editor of The Economist, and the author of The Dream of Reason and The Dream of Enlightenment, one of the reasons Descartes and Thomas Hobbes continue to be debated in the second decade of the twenty-first century, is that they still have something to say to us that remains relevant on questions such as, "What does the advance of science entail for our understanding of ourselves and our ideas of God?" and "How is government to deal with religious diversity."[171]

In her 2018 interview with Tyler Cowen, Agnes Callard described Descartes' thought experiment in the Meditations, where he encouraged a complete, systematic doubting of everything that you believe, to "see what you come to". She said, "What Descartes comes to is a kind of real truth that he can build upon inside of his own mind."[172] She said that Hamlet's monologues—"meditations on the nature of life and emotion"—were similar to Descartes' thought experiment. Hamlet/Descartes were "apart from the world", as if they were "trapped" in their own heads.[172] Cowen asked Callard if Descartes actually found any truths through his thought experiment or was it just "an earlier version of the contemporary argument that we're living in a simulation, where the evil demon is the simulation rather than Bayesian reasoning?" Callard agreed that this argument can be traced to Descartes, who had said that he had refuted it. She clarified that in Descartes' reasoning, you do "end up back in the mind of God"—in a "universe God has created" that is the "real world"...The whole question is about being connected to reality as opposed to being a figment. If you're living in the world God created, God can create real things. So you're living in a real world."[172]

Purported Rosicrucianism

[edit]The membership of Descartes to the Rosicrucians is debated.[173]

The initials of his name have been linked to the R.C. acronym widely used by Rosicrucians.[174] Furthermore, in 1619 Descartes moved to Ulm which was a well renowned international center of the Rosicrucian movement.[174] During his journey in Germany, he met Johannes Faulhaber who had previously expressed his personal commitment to join the brotherhood.[175]

Descartes dedicated the work titled The Mathematical Treasure Trove of Polybius, Citizen of the World to "learned men throughout the world and especially to the distinguished B.R.C. (Brothers of the Rosy Cross) in Germany". The work was not completed and its publication is uncertain.[176]

Bibliography

[edit]Writings

[edit]- 1618. Musicae Compendium. A treatise on music theory and the aesthetics of music, which Descartes dedicated to early collaborator Isaac Beeckman (written in 1618, first published—posthumously—in 1650).[177]: 127–129

- 1626–1628. Regulae ad directionem ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). Incomplete. First published posthumously in Dutch translation in 1684 and in the original Latin at Amsterdam in 1701 (R. Des-Cartes Opuscula Posthuma Physica et Mathematica). The best critical edition, which includes the Dutch translation of 1684, is edited by Giovanni Crapulli (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1966).

- c. 1630. De solidorum elementis. Concerns the classification of Platonic solids and three-dimensional figurate numbers. Said by some scholars to prefigure Euler's polyhedral formula. Unpublished; discovered in Descartes' estate in Stockholm 1650, soaked for three days in the Seine in a shipwreck while being shipped back to Paris, copied in 1676 by Leibniz, and lost. Leibniz's copy, also lost, was rediscovered circa 1860 in Hannover.[178]

- 1630–1631. La recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle (The Search for Truth by Natural Light) unfinished dialogue published in 1701.[179]: 264ff