Church, Francis Pharcellus - A00024

"Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world."

Francis Pharcellus Church (February 22, 1839 – April 11, 1906) was an American publisher and editor. In 1897, Church wrote the editorial "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus". Produced in response to eight-year-old Virginia O'Hanlon's letter asking whether Santa Claus was real, the widely republished editorial has become one of the most famous ever written.

Born in Rochester, New York, Church graduated from Columbia University and embarked on a career in journalism. With his brother, William Conant Church, Francis founded and edited several periodicals including The Army and Navy Journal, The Galaxy, and the Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal. He was a war correspondent for The New York Times during the American Civil War. He worked at The Sun in the early 1860s and again from 1874 until his death, writing thousands of editorials.

Church died in New York City and was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

Early life and education

[edit]Francis "Frank" Pharcellus Church was born in Rochester on February 22, 1839, to Pharcellus Church, a Baptist minister,[1][2] and Chara Emily Church (née Conant). He had three sisters; an older brother, William Conant Church;[2] and a younger brother, John Adams Church.[3] As a child, Francis looked up to William "as his 'big brother' and was his 'admiring satellite'."[4] In 1848, the family moved to Boston, where Pharcellus preached at Bowdoin Square Baptist Church and edited the Watchman and Reflector, a weekly Baptist newspaper. In 1852, Pharcellus' health failed; he resigned his pastorship and moved the family to Chara's home in Vermont. The following year, the family moved a final time, to Brooklyn.[4] Francis began to attend Manhattan's Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School, whose headmaster was Charles Anthon.[5] His education was centered around math and foreign languages.[3]

Francis Church matriculated at Columbia College in New York City, where he graduated with honors in 1859.[1] He earned a Master of Arts two years later.[6] Although Church had entered university studying law and divinity,[1][7] and spent a time studying under the judge Hooper C. Van Vorst,[5] he soon switched his focus completely to writing[1] and had graduated Columbia studying journalism.[7]

Writing and publishing career

[edit]After graduation, Church found work at The New York Chronicle, which was published by his father and brother. For a time after William left to work at The Sun, Francis Church was the chief assistant at the Chronicle, but he eventually left to work at The Sun as well.[3] In 1862, he covered the American Civil War for The New York Times.[2]

In 1863, Church, his brother William, and others established The Army and Navy Journal[3] to promote loyalty to the Union during the Civil War and report on military affairs. During the war, Church worked for the Journal as a war correspondent, and from 1863 to 1865, he was an editor and publisher of the Journal.[2] He remained co-publisher until 1874.[3]

In 1866, the brothers founded the Galaxy literary magazine as a competitor to The Atlantic Monthly;[8]: 137 [3] Church was a publisher for two years[3] and an editor there until 1872[2] or 1878.[3] The Dictionary of Literary Biography credits Francis with doing "most of the editorial work."[3] As editors, the brothers became known for their heavy-handed style, for instance cutting major parts of Rebecca Harding Davis's Waiting for the Verdict when they serialized it.[9] Supported by literary figures, notably Edmund Clarence Stedman, the brothers worked to attract the best authors possible to their publication, though they focused on New York authors and largely ignored the well-established literary society in New England.[3] Stedman, while speaking about the editors in 1903, stated that the magazine focused on featuring authors from across the United States and did not focus on publishing works from popular authors.[10]

They published the magazine fortnightly for a year, then switched to a monthly format. In 1870, Church proposed that Mark Twain contribute a "Memoranda" column in the magazine, a request Twain accepted; he edited the column from May 1870 to March 1871. Altogether, the magazine published the work of more than 600 authors,[3] including Rebecca Harding Davis, Henry James, John William De Forest, Rose Terry Cooke, John Esten Cooke, and Constance Fenimore Woolson.[3][11] The magazine's circulation peaked around 21,000 in 1871 and fell dramatically afterwards.[3] The Galaxy merged with the Atlantic Monthly in 1878.[8]: 137

Church also managed the Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal with his brother from 1870 to 1895.[1][3] He was re-hired as a part-time editor and writer at The Sun in 1874.[2][3] He started working full-time there after leaving The Galaxy.[2] In this capacity, Church published thousands of editorials, most of which attracted little note.[3] One of his more popular editorials was in response to a maid asking about etiquette, after which Church wrote a series of additional replies to letters asking for advice.[12] He continued to work for The Sun until his death in 1906.[2][3]

Edward Page Mitchell, The Sun's editor-in-chief, later said Church had "a knowledge of journalistic history and an insight into journalistic character that could hardly be expected of any but a major figure in the profession."[3] Mitchell also considered Church "energetic and a brilliant conversationalist."[7] An obituary published in The New York Times described Church as not being well known among literary circles because his reputation had been "merged" with that of The Sun, but among those who knew him he was "highly and justly esteemed." It said his editorial style specialized in treating theological topics "from a secular point of view."[13] [14] He disliked politics.[7]

"Yes, Virginia"

[edit]In 1897, Mitchell gave Church a letter written to The Sun by 8-year-old Virginia O'Hanlon, who wanted to know whether there truly is a Santa Claus.[15] In Church's 416-word response,[7] he wrote that Santa exists "as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist".[16] "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus"[17] became Church's best-known work and the most reprinted editorial in newspaper history.[18]

Mitchell reported that Church, who was initially reluctant to write a response, produced it "in a short time"[3] during an afternoon.[19]: 90 Upon publication on September 21, 1897, journalist Charles Anderson Dana described Church's writing as "Real literature," and said, "Might be a good idea to reprint it every Christmas—yes, and even tell who wrote it!"[15]

The editorial was first reprinted five years later to answer readers' demand for it. The Sun started reprinting the editorial annually in 1920 at Christmas, and continued until the paper's bankruptcy in 1950.[20] Because The Sun traditionally did not byline their editorials, Church was not known to be the author until his death in 1906.[21] The editorial is just one of two whose authorship The Sun disclosed.[7]

The editorial, which has been described as "the most famous editorial in history", has been translated into 20 languages, set to music, and adapted into at least two movies.[22]: 244–245 [23] A book based on the editorial, Is there a Santa Claus?, was published in 1921.[3]

Personal life and death

[edit]

In 1871, he married Elizabeth Wickham, who was from Philadelphia.[24][25] In 1882 or 1883, Church moved from 107 East 35th Street to the Florence Apartment House, located at East 18th Street and East Union Place (now known as Park Avenue South). He and his wife lived there until 1890.[26] They had no children.[19]: 91

He was a member of the Sons of the Revolution, the National Sculpture Society, and the Century Association.[2]

Church died in New York City on April 11, 1906, at the age of 67,[1] at his home on 46 East 30th Street.[5] He had an unknown illness for several months before his death.[25] He was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "'His Art Alone Endures'". The Tribune. December 9, 1930. p. 6. Retrieved December 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mynatt, Jenai (2004). Contemporary authors. [electronic resource] : a bio-bibliographical guide to current writers in fiction, general nonfiction, poetry, journalism, drama, motion pictures, television, and other fields. Detroit, Michigan: Gale. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-7876-9295-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Frasca, Ralph (1989). "William Conant Church (August 11, 1836–May 23, 1917) and Francis Pharcellus Church (February 22, 1839–April 11, 1906)". Dictionary of Literary Biography.

- ^ a b Bigelow, Donald Nevius (1952). William Conant Church & the Army and Navy Journal. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-404-51576-8.

- ^ a b c "Obituary Notes". The Publishers' Weekly: 1173–1174. April 14, 1906.

- ^ "Francis Pharcellus Church". New-York Tribune. April 12, 1906. p. 2. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Ranniello, Bruno (December 25, 1969). "'Yes, Virginia' Editorialist: Francis Pharcellus Church". The Bangor Daily News. p. 22. Retrieved December 20, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Frank Michael (1928). The story of the Sun, New York: 1833-1928. D. Appleton and Co.

- ^ Mott, Frank Luther (1967). A History of American Magazines Volume III: 1865–1885. Harvard University Press. pp. 21–22. LCCN 39-2823.

- ^ Scholnick, Robert (1972). "Whitman and the Magazines: Some Documentary Evidence". American Literature. 44 (2): 222–246. doi:10.2307/2924507. ISSN 0002-9831. JSTOR 2924507 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Twain, Mark (1999). Mark Twain at the Buffalo express : articles and sketches by America's favorite humorist. DeKalb : Northern Illinois University Press. pp. xxxi, xxxix. ISBN 978-0-87580-249-7.

- ^ Gilbert, Kevin (2015). "Famous New Yorker: Francis Pharcellus Church" (PDF). New York News Publisher's Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2021.

- ^ "Francis P. Church". The New York Times. April 13, 1906. p. 10. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Francis P. Church". The New York Times. April 13, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Turner, Hy B. (1999). When giants ruled : the story of Park Row, New York's great newspaper street. New York : Fordham University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-8232-1943-8.

- ^ Editorial Board (December 24, 2014). "'Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus': Read the iconic 1897 editorial that continues to bring Christmas joy". New York Daily News.

- ^ "'Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus'". Newseum. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (Spring 2005). "The grudging emergence of American journalism's classic editorial: New details about 'Is There A Santa Claus?'". American Journalism Review. 22 (2). University of Maryland, College Park: Philip Merrill College of Journalism: 41–61. doi:10.1080/08821127.2005.10677639. S2CID 146945285. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ a b Forbes, Bruce David (October 10, 2007). Christmas A Candid History. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520933729. ISBN 978-0-520-93372-9.

- ^ Applebome, Peter (December 13, 2006). "Tell Virginia the Skeptics Are Still Wrong". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Sebakijje, Lena. "Research Guides: Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Bowler, Gerald (2005). Santa Claus : a biography. Toronto : McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-1532-8.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (September 21, 1997). "Yes, Virginia, a Thousand Times Yes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Hamersly, Lewis Randolph; Leonard, John W.; Mohr, William Frederick; Knox, Herman Warren; Holmes, Frank R.; Downs, Winfield Scott (1907). Who's who in New York City and State. L.R. Hamersly Company. p. 280.

- ^ a b "Francis P. Church Dead". The New York Times. April 12, 1906. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Gretchko, John M. (2014). "The Florence". Leviathan. 11: 22–32. doi:10.1353/lvn.2014.0014. S2CID 201764074. ProQuest 1529942018 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Honored". Livingston County Daily Press and Argus. May 23, 2016. pp. A2. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

"Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" is a line from an editorial by Francis Pharcellus Church. Written in response to a letter by eight-year-old Virginia O'Hanlon asking whether Santa Claus was real, the editorial was first published in the New York newspaper The Sun on September 21, 1897.

"Is There a Santa Claus?" was initially published uncredited and Church's authorship was not disclosed until after his death in 1906. The editorial was quickly republished by other New York newspapers. Though initially reluctant to do the same, The Sun soon began regularly republishing the editorial during the Christmas and holiday season, including every year from 1924 to 1950, when the paper ceased publication.

The editorial is widely reprinted in the United States during the holiday season, and is the most reprinted newspaper editorial in the English language. It has been translated into around 20 languages and adapted as television specials, a film, a musical, and a cantata.

Background

[edit]Francis Pharcellus Church

[edit]Francis Pharcellus Church (February 22, 1839 – April 11, 1906) was an American publisher and editor. He and his brother William Conant Church founded and edited several publications: The Army and Navy Journal (1863), The Galaxy (1866), and the Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal (1870). Before the outbreak of the American Civil War he had worked in journalism, first at his father's New-York Chronicle and later at the New York newspaper The Sun. Church left The Sun in the early 1860s but returned to work there part-time in 1874. After The Galaxy merged with The Atlantic Monthly in 1878 he joined The Sun full-time as an editor and writer. Church wrote thousands of editorials at the paper,[1] and became known for writing on religious topics from a secular point of view.[2][3] After Church's death, his friend J. R. Duryee wrote that "by nature and training [he] was reticent about himself, highly sensitive and retiring".[4]

The Sun

[edit]In 1897, The Sun was one of the most prominent newspapers in New York City, having been developed by its long-time editor, Charles Anderson Dana, over the previous thirty years.[5] Their editorials that year were described by the scholar W. Joseph Campbell as favoring "vituperation and personal attack".[6] Campbell also wrote that the management of the paper was reluctant to republish content.[6]

Writing and publication

[edit]

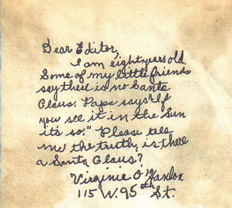

In 1897, Philip O'Hanlon, a surgeon, was asked by his eight-year-old daughter, Virginia O'Hanlon, whether Santa Claus existed. His answer did not convince her, and Virginia decided to pose the question to The Sun.[7] Sources conflict over whether her father suggested writing the letter,[8] or she elected to on her own.[7] In her letter Virginia wrote that her father had told her "If you see it in The Sun it's so."[8] O'Hanlon later told The Sun that her father thought the newspaper would be "too busy" to respond to her question and had said to "[w]rite if you want to," but to not be disappointed if she got no response.[9] After sending the letter she looked for a response "day after day".[9] O'Hanlon later said that she had waited for an answer to her letter for long enough that she forgot about it. Campbell theorizes the letter was sent shortly after O'Hanlon's birthday in July and was "overlooked or misplaced" for a time.[10][a]

The Sun's editor-in-chief, Edward Page Mitchell, eventually gave the letter to Francis Church.[14] Mitchell reported that Church, who was initially reluctant to write a response, produced it "in a short time"[1] during a single afternoon.[15] Church's response was 416 words long[16] and was anonymously[17] published in The Sun on September 21, 1897,[18] shortly after the beginning of the school year in New York City.[19] The editorial appeared in the paper's third and last column of editorials that day, positioned below discussions of an election law in Connecticut, a newly invented chainless bicycle, and "British Ships in American Waters".[18]

Church was not disclosed as the editorial's author until after his 1906 death.[17] This sometimes led to inaccuracies: a republication in December 1897 by The Meriden Weekly Republican had attributed authorship to Dana, saying that the editorial could "hardly have been written" by any other employee of the paper.[20] The editorial is one of two whose authorship The Sun disclosed,[16] the other being Harold M. Anderson's "[Charles] Lindbergh Flies Alone". Campbell argued in 2006 that Church might not have welcomed The Sun's disclosure, noting that he was generally unwilling to disclose the authorship of other editorials.[21]

Summary

[edit]The editorial, as it first appeared in The Sun, was titled "Is There a Santa Claus?" and prefaced with the text of O'Hanlon's letter asking the paper to tell her the truth about the existence of Santa Claus. O'Hanlon wrote that some of her "little friends" had told her that he was not real.[b] Church's response began: "Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age." He continued to write that Santa Claus existed "as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist" and that the world would be "dreary" if he did not. Church argued that just because something could not be seen did not mean it was not real: "Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world." He concluded that:[23]

Initial reception

[edit]Virginia O'Hanlon was informed of the editorial from a friend who called her father, describing the editorial as "the most wonderful piece of writing I ever saw." She later told The Sun "I think that I have never been so happy in my life" as when she read Church's response. O'Hanlon continued to say that while she was initially very proud of her role in the editorial's publication, she eventually came to understand that "the important thing was" Church's writing.[9] In an interview later in life she credited it with shaping the direction of her life positively.[11][24]

The Sun's editor, Charles Anderson Dana, favorably received Church's editorial, deeming it "real literature". He also said that it "might be a good idea to reprint [the editorial] every Christmas—yes, and even tell who wrote it!"[14] The editorial's publication drew no commentary from contemporary New York newspapers.[25]

Later republication

[edit]While The Sun did not republish the editorial for five years, it soon appeared in other papers.[26] The Sun only republished the editorial after a number of reader requests.[27][c] After 1902, it did not appear in the paper again until 1906, shortly after Church's death. The paper began to re-publish the editorial more regularly after this, including six times in the ensuing ten years and, according to Campbell, gradually began to "warm to" the editorial.[29] During this period other newspapers began to republish the editorial.[29]

In 1918, The Sun wrote that they got many requests to "reprint again the Santa Claus editorial article" every Christmas season.[25] The paper would also mail readers copies of the editorial upon request; it received 163,840 requests in 1930 alone and had sent 200,000 copies out by 1936.[30][31] Virginia O'Hanlon also received mail about her letter until her 1971 death and would include a copy of the editorial in her replies.[32][33]The Sun started reprinting the editorial annually at Christmas after 1924, when the paper's editor-in-chief, Frank Munsey, placed it as the first editorial on December 23. This practice continued on the 23rd or 24th of the month until the paper's bankruptcy in 1950.[27][29]

"Is There a Santa Claus?" often appears in newspaper editorial sections during the Christmas and holiday season.[34] It has become the most reprinted editorial in any newspaper in the English language,[26][35] and has been translated into around 20 languages.[36] Campbell describes it as living on as "enduring inspiration in American journalism."[34] Journalist David W. Dunlap described "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" as one of the most famous lines in American journalism, placing it after "Headless body in topless bar" and "Dewey Defeats Truman".[37] William David Sloan, a journalism scholar, described the line as "perhaps America's most famous editorial quote" and the editorial as "the nation's best known."[38]

Adaptations and legacy

[edit]The 1921 book Is There a Santa Claus? was adapted from the editorial.[1] The editorial became better known with the rise of mass media.[30] The story of Virginia's inquiry and the response from The Sun was adapted in 1932 into an NBC-produced cantata, making it the only known editorial set to classical music.[39] In the 1940s it was read yearly by actress Fay Bainter over the radio.[30] The editorial has been adapted to film several times, including as a segment of the short film Santa Claus Story (1945).[40]

Elizabeth Press published the 1972 children's book Yes, Virginia that illustrated the editorial and included a brief history of those involved.[41] The highly fictionalized 1974 animated television special Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus aired on ABC. Animated by Bill Melendez, it won the 1975 Emmy Award for outstanding children's special.[39][40][42]

In the 1989 drama Prancer, the letter is read and referenced multiple times, as it is the favorite piece of literature of the main character, whose belief in Santa Claus is vital to her.[43] The 1991 live-action television film Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus starring Richard Thomas, Ed Asner, and Charles Bronson, was also based on the publication. The story was adapted into an eponymous 1996 holiday musical, with music and lyrics by David Kirchenbaum and book by Myles McDonnel.[39]

The 2009 animated television special Yes, Virginia aired on CBS and featured actors including Neil Patrick Harris and Beatrice Miller.[40] The special was written by the Macy's ad agency as part of their "Believe" Make-A-Wish fundraising campaign. A novelization based on the special was published the following year. Macy's later had the special adapted into a musical for students in third through sixth grade. The company gave schools the rights to perform the musical for free and awarded $1,000 grants to a hundred schools for staging the show.[44][45]

The phrase "Yes, Virginia, there is (a) ..." has often been used[46] to emphasize that "fantasies and myths are important" and can be "spiritually if not literally true".[47]

Analysis

[edit]The historian and journalist Bill Kovarik described the editorial as part of a broader "revival of the Christmas holiday" that took place during the late 19th century with the publication of various works such as Thomas Nast's art.[48] Scholar Stephen Nissenbaum wrote that the editorial reflected popular theology of the late Victorian era and that its content echoed that of sermons on the existence of God.[49] A 1914 editorial in The Outlook, building on The Sun, saw Santa Claus as a symbol of love, part of a child's developing image of God.[50]

The editorial's success has been used to offer insights to writing. Upon the centenary of the editorial's publication in 1997, the journalist Eric Newton, who at the time was working at the Newseum, described the editorial as representative of the sort of "poetry" that newspapers should publish as editorials, while Geo Beach in the Editor & Publisher trade magazine described Church's writing as "brave" and showing that "love, hope, belief—all have a place on the editorial page". Beach also wrote that newspapers should not hold "anything back", as The Sun had done by publishing the editorial in September rather than in the Christmas season. In 2005, Campbell wrote that the editorial, particularly The Sun's reluctance to republish it, could offer insight into the broader state of American newspapers in the late 19th century.[26]

Reception of the editorial has not been unanimously positive. As early as 1935, journalist Heywood Broun called the editorial a "phony piece of writing."[31] Members of the Christian Reformed Church in North America in Lynden, Washington criticized it in 1951 for encouraging Virginia to think of her friends as liars.[51] In 1997, the journalist Rick Horowitz wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that the editorial gave journalists an excuse to not write their own essays around Christmas: "they can just slap Francis Church's 'Yes, Virginia,' up there on the page and go straight to the office party."[52]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A copy of the letter, hand-written by Virginia and believed by her family to be the original and returned to them by the newspaper[11] was authenticated in 1998 by Kathleen Guzman, an appraiser on the television program Antiques Roadshow.[12] In 2007, the show appraised its value at around $50,000.[11] As of 2015, the letter was held by Virginia's great-granddaughter.[13]

- ^ Andy Rooney doubted that a young girl would refer to children her own age as "my little friends" and theorized that Virginia's father assisted her in composing the letter or even wrote it himself.[22]

- ^ While some sources state that the editorial was republished every year after 1897, it did not appear until December 1902, with the comment that "[S]ince its original publication, the Sun has refrained from reprinting the article on Santa Claus which appeared several years ago, but this year requests for its reproduction have been so numerous that we yield."[28]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Frasca, Ralph (1989). "William Conant Church (11 August 1836–23 May 1917) and Francis Pharcellus Church (22 February 1839–11 April 1906)". Dictionary of Literary Biography. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale.

- ^ Gilbert, Kevin (2015). "Famous New Yorker: Francis Pharcellus Church" (PDF). New York News Publisher's Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Francis P. Church". The New York Times. April 13, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 132.

- ^ a b Quigg, H. D. (December 22, 1958). "Virginia Tells of Santa Query 61 Years Past". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 12. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Strauss, Valerie (December 25, 2014). "Virginia of 'Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus' grew up to be a teacher". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "'Is There a Santa Claus?' The Sun's Virginia of 1897 Tells her Own Virginia That There Is, and Proves It". The Sun. New York City. December 25, 1914. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b c Gollom, Mark (December 22, 2019). "Yes, Virginia, your Christmas legacy lives on". CBC News. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "1897 'Yes, Virginia' Santa Claus Letter". Antiques Roadshow. Public Broadcasting Service. July 19, 1997. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Yes, there is a Santa Claus". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Turner 1999, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Forbes 2007, p. 90.

- ^ a b Ranniello, Bruno (December 25, 1969). "'Yes, Virginia' Editorialist: Francis Pharcellus Church". The Bangor Daily News. p. 22. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Sebakijje, Lena. "Research Guides: Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 134.

- ^ "Is There a Santa Claus?". The Meriden Weekly Republican. December 16, 1897. p. 9. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Rooney 2007.

- ^ ""Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus"". Newseum. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Yes Virginia – 66 years later". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. December 24, 1963. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Campbell, W. Joseph (Spring 2005). "The grudging emergence of American journalism's classic editorial: New details about 'Is There A Santa Claus?'". American Journalism Review. 22 (2). University of Maryland, College Park: Philip Merrill College of Journalism: 41–61. doi:10.1080/08821127.2005.10677639. ISSN 1067-8654. S2CID 146945285. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ a b Applebome, Peter (December 13, 2006). "Tell Virginia the Skeptics Are Still Wrong". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Campbell 2006, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c Kaplan, Fred (December 22, 1997). "A child's query echoes across the ages". The Boston Globe. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 1, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Manley, Jared L. (December 24, 1936). "Santa Claus Is Real in Famous Editorial". The Windsor Star. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 1, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morrison, Jim "Santa Junior"; McElhany, Jennifer. "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus". National Christmas Centre. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "Virginia O'Hanlon, Santa's Friend, Dies; Virginia O'Hanlon Dead at 81". The New York Times. May 14, 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 196.

- ^ Garza, Melita M.; Fuhlhage, Michael; Lucht, Tracy (July 27, 2023). The Routledge Companion to American Journalism History (1 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 393. doi:10.4324/9781003245131. ISBN 978-1-003-24513-1. S2CID 260256757.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (September 21, 1997). "Yes, Virginia, a Thousand Times Yes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (December 25, 2015). "1933 | P.S., Virginia, There's a New York Times, Too". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Sloan, William David (Fall 1979). "Question: 'Is There a Santa Claus?'". The Masthead. Rockville, Maryland: National Conference of Editorial Writers. pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Bowler 2000, pp. 252–253.

- ^ a b c Crump 2019, p. 349.

- ^ Long, Sidney (December 3, 1972). "... And a Partridge in a Pear Tree". The New York Times. p. BR8. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 119470293.

- ^ Woolery 1989, p. 464.

- ^ Campbell, Courtney (November 2, 2020). "Sam Elliott Reading 'Yes, Virginia' in 'Prancer' Gets Us in the Holiday Spirit". Wide Open Country. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (December 25, 2014). "Macy's gives its Santa musical to public schools for free – and gets tons of priceless publicity". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (August 22, 2012). "Giving Little Virginia Something to Sing About". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Lovinger 2000, p. 484.

- ^ Hirsch, Kett & Trefil 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Kovarik 2015, p. 73.

- ^ Nissenbaum 1997, p. 88.

- ^ "Fact, Fiction, And The Truth". The Outlook. April 4, 1914. pp. 746–749.

- ^ "Santa Survives Protest; Objection of Church Group to His Appearance Is Rejected". The New York Times. December 23, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 196–197.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bowler, Gerry, ed. (2000). "'Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus.'". The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Limited. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-0-7710-1531-1.

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2006). The Year That Defined American Journalism. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203700495. ISBN 978-1-135-20505-8.

- Crump, William D. (2019). Happy Holidays—Animated! A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and New Year's Cartoons on Television and Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 349. ISBN 978-1-4766-7293-9.

- Forbes, Bruce David (October 10, 2007). Christmas: A Candid History. Oakland, California: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520933729. ISBN 978-0-520-93372-9.

- Hirsch, Eric Donald; Kett, Joseph F.; Trefil, James S. (2002). The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-22647-4.

- Kovarik, Bill (2015). Revolutions in Communication: Media History from Gutenberg to the Digital Age. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-62892-479-4.

- Lovinger, Paul W. (2000). The Penguin Dictionary of American English Usage and Style. New York: Penguin Reference. ISBN 978-0-670-89166-5.

- Nissenbaum, Stephen (1997). The Battle For Christmas. New York: Vintage Books. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-679-74038-4.

- Rooney, Andy (2007). Common Nonsense. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-617-4.

- Turner, Hy B. (1999). When Giants Ruled: The Story of Park Row, New York's Great Newspaper Street. New York: Fordham University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-8232-1943-8.

- Woolery, George W. (1989). Animated TV Specials: The Complete Directory to the First Twenty-Five Years, 1962–1987. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 463–464. ISBN 978-0-8108-2198-9. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus (1897)

In 1897, Dr. Philip O'Hanlon, a coroner's assistant on Manhattan's Upper West Side, was asked a question by his then eight-year-old daughter, Virginia, which many a parent has been asked before: whether Santa Claus really exists. O'Hanlon deferred. He suggested Virginia wrote asking the question to one of New York's most prominent newspapers at the time, The Sun, assuring her that "If you see it in The Sun, it's so."

Dear Editor: I am 8 years old.

Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus.

Papa says, 'If you see it in The Sun it's so.'

Please tell me the truth; is there a Santa Claus?

The response to Virginia's letter by one of the paper's editors, Francis Pharcellus Church, remains the most reprinted editorial ever to run in any newspaper in the English language and found itself the subject of books, a film and television series. In his response Church goes beyond a simple "yes of course" to explore the philosophical issues behind Virginia's request to tell her "the truth" and in the process lampoon a certain skepticism which he had found rife in American society since the suffering of the Civil War. His message in short - there is a reality beyond the visible.

VIRGINIA, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men's or children's, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, VIRGINIA, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no VIRGINIAS. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

Not believe in Santa Claus! You might as well not believe in fairies! You might get your papa to hire men to watch in all the chimneys on Christmas Eve to catch Santa Claus, but even if they did not see Santa Claus coming down, what would that prove? Nobody sees Santa Claus, but that is no sign that there is no Santa Claus. The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see. Did you ever see fairies dancing on the lawn? Of course not, but that's no proof that they are not there. Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world.

You may tear apart the baby's rattle and see what makes the noise inside, but there is a veil covering the unseen world which not the strongest man, nor even the united strength of all the strongest men that ever lived, could tear apart. Only faith, fancy, poetry, love, romance, can push aside that curtain and view and picture the supernal beauty and glory beyond. Is it all real? Ah, VIRGINIA, in all this world there is nothing else real and abiding.

No Santa Claus! Thank God! he lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.

No comments:

Post a Comment