88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Dick Cheney | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait, 2003 | |||

| 46th Vice President of the United States | |||

| In office January 20, 2001 – January 20, 2009 | |||

| President | George W. Bush | ||

| Preceded by | Al Gore | ||

| Succeeded by | Joe Biden | ||

| 17th United States Secretary of Defense | |||

| In office March 21, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |||

| President | George H. W. Bush | ||

| Deputy | Donald J. Atwood Jr. | ||

| Preceded by | Frank Carlucci | ||

| Succeeded by | Les Aspin | ||

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wyoming's at-large district | |||

| In office January 3, 1979 – March 20, 1989 | |||

| Preceded by | Teno Roncalio | ||

| Succeeded by | Craig L. Thomas | ||

| |||

| 7th White House Chief of Staff | |||

| In office November 21, 1975 – January 20, 1977 | |||

| President | Gerald Ford | ||

| Preceded by | Donald Rumsfeld | ||

| Succeeded by | Hamilton Jordan (1979) | ||

| White House Deputy Chief of Staff | |||

| In office December 18, 1974 – November 21, 1975 | |||

| President | Gerald Ford | ||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||

| Succeeded by | Landon Butler | ||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | Richard Bruce Cheney January 30, 1941 Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S. | ||

| Died | November 3, 2025 (aged 84) Northern Virginia, U.S. | ||

| Political party | Republican | ||

| Spouse | |||

| Children | |||

| Education |

| ||

| Signature |  | ||

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Dick Cheney (born January 30, 1941, Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S.—died November 3, 2025) was the 46th vice president of the United States (2001–09) in the Republican administration of Pres. George W. Bush and secretary of defense (1989–93) in the administration of Pres. George H.W. Bush. As vice president, Cheney wielded immense power and was incredibly polarizing.

Education and family

Cheney was the son of Richard Herbert Cheney, a soil-conservation agent, and Marjorie Lauraine Dickey Cheney. He was born in Nebraska and grew up in Casper, Wyoming. He entered Yale University in 1959 but failed to graduate. Cheney earned bachelor’s (1965) and master’s (1966) degrees in political science from the University of Wyoming and was a doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin.

On August 29, 1964, he married Lynne Vincent. While Cheney worked as an aid to Wisconsin Gov. Warren Knowles, his wife received a doctorate in British literature from the University of Wisconsin. She later served as chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH; 1986–93), where she was criticized by liberals for undermining the agency and by conservatives for opposing the closure of a controversial NEH-funded exhibit by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe in Cincinnati, Ohio. The couple had two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary.

Government posts: White House chief of staff and U.S. representative

In 1968 Cheney moved to Washington, D.C., to serve as a congressional fellow, and, beginning in 1969, he worked in the administration of Pres. Richard Nixon. After leaving government service briefly in 1973, he became a deputy assistant to Pres. Gerald Ford in 1974 and his chief of staff from 1975 to 1977. In 1978 he was elected from Wyoming to the first of six terms in the United States House of Representatives, where he rose to become the Republican whip. In the House, Cheney took conservative positions on abortion, gun control, and environmental regulation, among other issues. In 1978 he suffered the first of several mild heart attacks, and he underwent quadruple-bypass surgery in 1988.

From 1989 to 1993 he served as secretary of defense in the administration of Pres. George Bush, presiding over reductions in the military following the breakup of the Soviet Union. Cheney also oversaw the U.S. military invasion of Panama and the participation of U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf War. After President Bush lost his reelection bid in 1992, Cheney became a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. In 1995 he became the chairman and chief executive officer of the Halliburton Company, a supplier of technology and services to the oil and gas industries.

Vice president

After George W. Bush’s primary victories secured his nomination for the presidency of the United States, Cheney was appointed to head Bush’s vice presidential search committee. Few expected that Cheney himself would eventually become the Republican vice presidential candidate. Two weeks after election day, Cheney suffered another mild heart attack, though he quickly resumed his duties as leader of Bush’s presidential transition team.

As vice president, Cheney was active and used his influence to help shape the administration’s energy policy and foreign policy in the Middle East. He played a central, controversial role in conveying intelligence reports that Saddam Hussein of Iraq had developed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in violation of resolutions passed by the United Nations—reports used by the Bush administration to initiate the Iraq War. However, Iraq had no WMDs that could be found. Following the collapse of Saddam’s regime, Cheney’s former company, Halliburton, secured lucrative reconstruction contracts from the U.S. government, raising the spectre of favoritism and possible wrongdoing—allegations that damaged Cheney’s public reputation. Critics, who had long charged Cheney with being a secretive public servant, included members of Congress who brought suit against him for not disclosing records used to form the national energy policy.

Later life

After leaving office in 2009, Cheney remained in the public eye, often speaking on political matters. In 2010 he suffered his fifth heart attack. Two years later he had a heart transplant. His autobiography, In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir (cowritten with his daughter Liz Cheney), was published in 2011. Cheney also wrote, with his heart surgeon, Heart: An American Medical Odyssey (2013) and, with Liz Cheney, Exceptional: Why the World Needs a Powerful America (2015).

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Richard Bruce Cheney[a] (January 30, 1941 – November 3, 2025) was an American politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. His tenure is often called the most powerful vice presidency in American history, with many pundits and historians noting that he was the first vice president to be more powerful than the presidents they served under.[4][5] A member of the Republican Party, Cheney previously served as White House chief of staff for President Gerald Ford, the U.S. representative for Wyoming's at-large congressional district from 1979 to 1989, and as the 17th United States secretary of defense in the administration of President George H. W. Bush. He was also considered by many to be the architect of the Iraq War.[6]

Born and raised in Lincoln, Nebraska, Cheney later lived in Casper, Wyoming.[7] He attended Yale University before earning a Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts in political science from the University of Wyoming. He began his political career as an intern for Congressman William A. Steiger, eventually working his way into the White House during the Nixon and Ford administrations. He served as White House chief of staff from 1975 to 1977. In 1978, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, and represented Wyoming's at-large congressional district from 1979 to 1989, briefly serving as House minority whip in 1989. He was appointed Secretary of Defense during the presidency of George H. W. Bush, and held the position for most of Bush's term from 1989 to 1993.[8] As secretary, he oversaw Operation Just Cause in 1989 and Operation Desert Storm in 1991. While out of office during the Clinton administration, he was the chairman and CEO of Halliburton from 1995 to 2000.

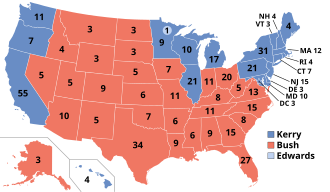

In July 2000, Cheney was chosen by presumptive Republican presidential nominee George W. Bush as his running mate in the 2000 presidential election. They defeated their Democratic opponents, incumbent vice president Al Gore and senator Joe Lieberman. In 2004, Cheney was reelected to his second term as vice president with Bush as president, defeating their Democratic opponents Senators John Kerry and John Edwards. During Cheney's tenure as vice president, he played a leading behind-the-scenes role in the Bush administration's response to the September 11 attacks and coordination of the Global War on Terrorism. He was an early proponent of the decision to invade Iraq, falsely alleging that the Saddam Hussein regime possessed weapons of mass destruction and had an operational relationship with Al-Qaeda; however, neither allegation was ever substantiated. He also pressured the intelligence community to provide intelligence consistent with the administration's rationales for invading Iraq. Cheney was often criticized for the Bush administration's policies regarding the campaign against terrorism, for his support of wiretapping by the National Security Agency (NSA), and for his endorsement of the U.S.'s "enhanced interrogation" torture program.[9][10][11][12]

He publicly disagreed with President Bush's position against same-sex marriage in 2004,[13] but also said it was "appropriately a matter for the states to decide".[14] Cheney ended his vice presidential tenure as a deeply unpopular figure in American politics with an approval rating of 13 percent.[15] His peak approval rating in the wake of the September 11 attacks was 68 percent.[16] After leaving the vice presidency, Cheney became critical of modern Republican leadership, including Donald Trump, and endorsed Trump's challenger in 2024, Democrat Kamala Harris.[17] Cheney died on November 3, 2025,[18][19] from complications related to pneumonia and vascular disease.[20]

Early life and education

Richard Bruce Cheney was born on January 30, 1941, in Lincoln, Nebraska, the son of Marjorie Lorraine (née Dickey) and Richard Herbert Cheney.[19] He was of predominantly English, as well as Welsh, Irish, and French Huguenot ancestry. His father was a soil conservation agent for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and his mother was a softball star in the 1930s;[21] Cheney was one of three children. He attended Calvert Elementary School[22][23] before his family moved to Casper, Wyoming,[24] where he attended Natrona County High School.[25][26]

He attended Yale University, but by his own account had problems adjusting to the college, and dropped out.[27][28] Among the influential teachers from his days in New Haven was H. Bradford Westerfield, whom Cheney repeatedly credited with having helped to shape his approach to foreign policy.[29] He later attended the University of Wyoming, where he earned both a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts in political science. He subsequently started, but did not finish, doctoral studies in political science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[30]

In November 1962, at the age of 21, Cheney was convicted of driving while intoxicated (DWI). He was arrested for DWI again the following year.[31] Cheney said that the arrests made him "think about where I was and where I was headed. I was headed down a bad road if I continued on that course."[32]

In 1964, he married Lynne Vincent, his high school sweetheart.[33]

When Cheney became eligible for the draft, during the Vietnam War, he applied for and received five draft deferments. In 1989, The Washington Post writer George C. Wilson interviewed Cheney as the next secretary of defense; when asked about his deferments, Cheney reportedly said, "I had other priorities in the '60s than military service."[34] Cheney testified during his confirmation hearings in 1989 that he received deferments to finish a college career that lasted six years rather than four, owing to sub-par academic performance and the need to work to pay for his education. Upon graduation, Cheney was eligible for the draft, but at the time, the Selective Service System was not inducting married men.[35] On October 26, 1965, the draft was expanded to include married men without children; Cheney's first daughter, Elizabeth, was born 9 months and two days later.[36][35] Cheney's fifth and final deferment granted him "3-A" status, a "hardship" deferment available to men with dependents. On January 30, 1967, Cheney turned 26 and was no longer eligible for the draft.[36]

In 1966, Cheney dropped out of the doctoral program at the University of Wisconsin to work as staff aide for Governor Warren Knowles.[37]

In 1968 Cheney was awarded an American Political Science Association congressional fellowship and moved to Washington, D.C.[37]

Early career

Cheney's political career began in 1969, as an intern for Congressman William A. Steiger during the Richard Nixon Administration. He then joined the staff of Donald Rumsfeld, who was then Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity from 1969 to 1970.[31] He held several positions in the years that followed: White House Staff Assistant in 1971, Assistant Director of the Cost of Living Council from 1971 to 1973, and Deputy Assistant to the president from 1974 to 1975. As deputy assistant, Cheney suggested several options in a memo to Rumsfeld, including use of the U.S. Justice Department, that the Ford administration could use to limit damage from an article, published by The New York Times, in which investigative reporter Seymour Hersh reported that U.S. Navy submarines had tapped into Soviet undersea communications as part of a highly classified program, Operation Ivy Bells.[38][39]

White House chief of staff

Cheney was Assistant to the President and White House deputy chief of staff under Gerald Ford from December, 1974 to November, 1975.[40][41][42] When Rumsfeld was named Secretary of Defense, Cheney became White House chief of staff, succeeding Rumsfeld.[31] He later was campaign manager for Ford's 1976 presidential campaign.[43]

U.S. House of Representatives (1979–1989)

Elections

In 1978, Cheney was elected to represent Wyoming in the U.S. House of Representatives and succeeded retiring Democratic Congressman Teno Roncalio, having defeated his Democratic opponent, Bill Bagley. Cheney was re-elected five times, serving until 1989.[44]

Tenure

Leadership

In 1987, he was elected Chairman of the House Republican Conference. The following year, he was elected House minority whip.[45] He served for two and a half months before he was appointed Secretary of Defense instead of former U.S. senator John G. Tower, whose nomination had been rejected by the U.S. Senate in March 1989.[46]

Votes

Cheney voted against the creation of the U.S. Department of Education, citing his concern over budget deficits and expansion of the federal government, and claiming that the department was an encroachment on states' rights.[47] He voted against funding Head Start, but reversed his position in 2000.[48]

Cheney initially opposed establishing a national holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1978, but supported creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day five years later, in 1983.[49]

Cheney supported Bob Michel's (R-IL) bid to become Republican Minority Leader.[50] In April 1980, Cheney endorsed Governor Ronald Reagan for president, becoming one of Reagan's earliest supporters.[51]

In 1986, after President Reagan vetoed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, a bill set to impose economic sanctions on South Africa for its policy of apartheid, Cheney was one of 83 Representatives to vote against overriding Reagan's veto.[52] In later years, he articulated his opposition to unilateral sanctions against many different countries, stating "they almost never work"[53] and that in that case they might have ended up hurting the people instead.[54]

In 1986, Cheney, along with 145 Republicans and 31 Democrats, voted against a non-binding Congressional resolution calling on the South African government to release Nelson Mandela from prison, after the Democrats defeated proposed amendments that would have required Mandela to renounce violence sponsored by the African National Congress (ANC) and requiring it to oust the communist faction from its leadership; the resolution was defeated. Appearing on CNN, Cheney addressed criticism for this, saying he opposed the resolution because the ANC "at the time was viewed as a terrorist organization and had a number of interests that were fundamentally inimical to the United States."[55]

Committee assignments

Originally declining, U.S. congressman Barber Conable persuaded Cheney to join the moderate Republican Wednesday Group in order to move up the leadership ranks. He was elected Chairman of the Republican Policy Committee from 1981 to 1987. Cheney was the Ranking Member of the Select Committee to investigate the Iran-Contra Affair.[31][56][57] He promoted Wyoming's petroleum and coal businesses as well.[58]

Secretary of Defense (1989–1993)

President George H. W. Bush nominated Cheney for the office of Secretary of Defense immediately after the U.S. Senate failed to confirm John Tower for that position.[59] The senate confirmed Cheney by a vote of 92 to 0[59] and he served in that office from March 1989 to January 1993. He directed the United States invasion of Panama and Operation Desert Storm in the Middle East. In 1991, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Bush.[45][37] Later that year, he received the U.S. senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[60]

Cheney said that his time at the Pentagon was the most rewarding period of his public service career, calling it "the one that stands out."[61] In 2014, Cheney recounted that when he met with President Bush to accept the offer, he passed a painting in the private residence entitled The Peacemakers, which depicted President Lincoln, General Grant, and William Tecumseh Sherman. "My great-grandfather had served under William Tecumseh Sherman throughout the war," Cheney said, "and it occurred to me as I was in the room as I walked in to talk to the President about becoming Secretary of Defense, I wondered what he would have thought that his great-grandson would someday be in the White House with the President talking about taking over the reins of the U.S. military."[62]

Early tenure

Cheney worked closely with Pete Williams, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, and Paul Wolfowitz, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, from the beginning of his tenure. He focused primarily on external matters, and left most of the internal DoD management to Deputy Secretary of Defense Donald Atwood.[46]

Budgetary practices

Cheney's most immediate issue as Secretary of Defense was the Department of Defense budget. Cheney deemed it appropriate to cut the budget and downsize the military, following the Reagan Administration's peacetime defense buildup at the height of the Cold War.[63] As part of the fiscal year 1990 budget, Cheney assessed the requests from each of the branches of the armed services for such expensive programs as the Avenger II Naval attack aircraft, the B-2 stealth bomber, the V-22 Osprey tilt-wing helicopter, the Aegis destroyer, and the MX missile, totaling approximately $4.5 billion in light of changed world politics.[46] Cheney opposed the V-22 program, for which Congress had already appropriated funds, and initially refused to issue contracts for it before relenting.[64] When the 1990 Budget came before Congress in the summer of 1989, it settled on a figure between the Administration's request and the House Armed Services Committee's recommendation.[46]

In subsequent years under Cheney, the proposed and adopted budgets followed patterns similar to that of 1990. Early in 1991, he unveiled a plan to reduce military strength by the mid-1990s to 1.6 million, compared with 2.2 million when he entered office. Cheney's 1993 defense budget was reduced from 1992, omitting programs that Congress had directed the Department of Defense to buy weapons that it did not want, and omitting unrequested reserve forces.[46]

Over his four years as Secretary of Defense, Cheney downsized the military and his budgets showed negative real growth, despite pressures to acquire weapon systems advocated by Congress. The Department of Defense's total obligational authority in current dollars declined from $291 billion to $270 billion. Total military personnel strength decreased by 19 percent, from about 2.2 million in 1989 to about 1.8 million in 1993.[46] Notwithstanding the overall reduction in military spending, Cheney directed the development of a Pentagon plan to ensure U.S. military dominance in the post-Cold War era.[65]

Political climate and agenda

Cheney publicly expressed concern that nations such as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, could acquire nuclear components after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The end of the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact obliged the first Bush Administration to reevaluate the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO's) purpose and makeup. Cheney believed that NATO should remain the foundation of European security relationships and that it would remain important to the United States in the long term; he urged the alliance to lend more assistance to the new democracies in Eastern Europe.[46]

Cheney's views on NATO reflected his skepticism about prospects for peaceful social development in the former Eastern Bloc countries, where he saw a high potential for political uncertainty and instability. He felt that the Bush Administration was too optimistic in supporting General Secretary of the CPSU Mikhail Gorbachev and his successor, Russian President Boris Yeltsin.[46] Cheney not only wanted the break-up of the USSR but also of Russia itself.[66] Cheney worked to maintain strong ties between the United States and its European allies.[67]

Cheney persuaded the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to allow bases for U.S. ground troops and war planes in the nation. This was an important element of the success of the Gulf War, as well as a lightning-rod for Islamists, such as Osama bin Laden, who opposed having non-Muslim armies near their holy sites.[68]

International situations

Using economic sanctions and political pressure, the United States mounted a campaign to drive Panamanian ruler General Manuel Antonio Noriega from power after he fell from favor.[46] In May 1989, after Guillermo Endara had been duly elected President of Panama, Noriega nullified the election outcome, drawing intensified pressure. In October, Noriega suppressed a military coup, but in December, after soldiers of the Panamanian army killed a U.S. serviceman, the United States invasion of Panama began under Cheney's direction. The stated reason for the invasion was to seize Noriega to face drug charges in the United States, protect U.S. lives and property, and restore Panamanian civil liberties.[69] Although the mission was controversial,[70] U.S. forces achieved control of Panama and Endara assumed the presidency; Noriega was convicted and imprisoned on racketeering and drug trafficking charges in April 1992.[71]

In 1991, the Somali Civil War drew the world's attention. In August 1992, the United States began to provide humanitarian assistance, primarily food, through a military airlift. At President Bush's direction, Cheney dispatched the first of 26,000 U.S. troops to Somalia as part of the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), designed to provide security and food relief.[46] Cheney's successors as Secretary of Defense, Les Aspin and William J. Perry, had to contend with both the Bosnian and Somali issues.[72]

Iraqi invasion of Kuwait

On August 1, 1990, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein sent the invading Iraqi forces into neighboring Kuwait, a small petroleum-rich state long claimed by Iraq as part of its territory. This invasion sparked the initiation of the Persian Gulf War and it brought worldwide condemnation.[73] An estimated 140,000 Iraqi troops quickly took control of Kuwait City and moved on to the Saudi Arabia/Kuwait border.[46] The United States had already begun to develop contingency plans for the defense of Saudi Arabia by the U.S. Central Command, headed by General Norman Schwarzkopf, because of its important petroleum reserves.[74][75]

U.S. and world reaction

Cheney and Schwarzkopf oversaw planning for what would become a full-scale U.S. military operation. According to General Colin Powell, Cheney "had become a glutton for information, with an appetite we could barely satisfy. He spent hours in the National Military Command Center peppering my staff with questions."[46]

Shortly after the Iraqi invasion, Cheney made the first of several visits to Saudi Arabia where King Fahd requested U.S. military assistance. The United Nations took action as well, passing a series of resolutions condemning Iraq's invasion of Kuwait; the UN Security Council authorized "all means necessary" to eject Iraq from Kuwait, and demanded that the country withdraw its forces by January 15, 1991.[73] By then, the United States had a force of about 500,000 stationed in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf. Other nations, including Britain, Canada, France, Italy, Syria, and Egypt, contributed troops, and other allies, most notably Germany and Japan, agreed to provide financial support for the coalition effort, named Operation Desert Shield.[46]

On January 12, 1991, Congress authorized Bush to use military force to enforce Iraq's compliance with UN resolutions on Kuwait.[73]

Military action

The first phase of Operation Desert Storm, which began on January 17, 1991, was an air offensive to secure air superiority and attack Iraqi forces, targeting key Iraqi command and control centers, including the cities of Baghdad and Basra. Cheney turned most other Department of Defense matters over to Deputy Secretary Donald J. Atwood Jr. and briefed Congress during the air and ground phases of the war.[46] He flew with Powell to the region to review and finalize the ground war plans.[73]

After an air offensive of more than five weeks, Coalition forces launched the ground war on February 24. Within 100 hours, Iraqi forces had been routed from Kuwait and Schwarzkopf reported that the basic objective – expelling Iraqi forces from Kuwait – had been met on February 27.[76] After consultation with Cheney and other members of his national security team, Bush declared a suspension of hostilities.[73] On working with this national security team, Cheney said, "there have been five Republican presidents since Eisenhower. I worked for four of them and worked closely with a fifth – the Reagan years when I was part of the House leadership. The best national security team I ever saw was that one. The least friction, the most cooperation, the highest degree of trust among the principals, especially."[77]

Aftermath

A total of 147 U.S. military personnel died in combat, and another 236 died as a result of accidents or other causes.[46][76] Iraq agreed to a formal truce on March 3, and a permanent cease-fire on April 6. There was subsequent debate about whether Coalition forces should have driven as far as Baghdad to oust Saddam Hussein from power. Bush agreed that the decision to end the ground war when they did was correct, but the debate persisted as Hussein remained in power and rebuilt his military forces.[46] Arguably the most significant debate concerned whether U.S. and Coalition forces had left Iraq too soon.[78][79] In an April 15, 1994, interview with C-SPAN, Cheney was asked if the U.S.-led Coalition forces should have moved into Baghdad. Cheney replied that occupying and attempting to take over the country would have been a "bad idea" and would have led to a "quagmire", explaining that:

Cheney regarded the Gulf War as an example of the kind of regional problem the United States was likely to continue to face in the future:[82]

Private-sector career

Between 1987 and 1989, during his last term in Congress, Cheney was on the board of the Council on Foreign Relations foreign policy organization.[83]

With the inauguration of the new Democratic administration under President Bill Clinton in January 1993, Cheney joined the American Enterprise Institute. He also served a second term as a Council on Foreign Relations director from 1993 to 1995.[83]

From October 1, 1995[84] to July 25, 2000,[85] he was chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Halliburton, a Fortune 500 company. Cheney resigned as CEO on the same day he was announced as George Bush's vice-presidential pick in the 2000 election.[86]

Cheney's record as CEO was subject to some dispute among Wall Street analysts. A 1998 merger between Halliburton and Dresser Industries attracted the criticism of some Dresser executives for Halliburton's lack of accounting transparency.[87] Halliburton shareholders pursued a class-action lawsuit alleging that the corporation artificially inflated its stock price during this period, though Cheney was not named as an individual defendant in the suit. In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling and allowed the case to continue in litigation.[88] Cheney was named in a December 2010 corruption complaint filed by the Nigerian government against Halliburton, which the company settled for $250 million.[89]

During Cheney's term, Halliburton changed its accounting practices regarding revenue realization of disputed costs on major construction projects.[90] Cheney resigned as CEO of Halliburton on July 25, 2000. As vice president, he argued that this step, along with establishing a trust and other actions, removed any conflict of interest.[91] Cheney's net worth, estimated to be between $19 million and $86 million,[92] was largely derived from his post at Halliburton.[93] His 2006 gross joint income with his wife was nearly $8.82 million.[94]

He was also a member of the board of advisors of the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA) before becoming vice president.[68]

2000 presidential election

In early 2000, while CEO of Halliburton, Cheney headed Governor of Texas George W. Bush's vice-presidential search committee. On July 25, after reviewing Cheney's findings, Bush surprised some pundits by asking Cheney himself to join the Republican ticket.[31][95] However, a New York Times article which was published on July 28, 2000 acknowledged that the decision to select Cheney as Bush's Vice Presidential nominee was in fact secretly made "weeks" before it was formally announced.[96] Halliburton reportedly reached agreement on July 20 to allow Cheney to retire, with a package estimated at $20 million.[97]

A few months before the election Cheney put his home in Dallas up for sale and changed his drivers' license and voter registration back to Wyoming. This change was necessary to allow Texas' presidential electors to vote for both Bush and Cheney without contravening the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which forbids electors from voting for "an inhabitant of the same state with themselves"[98] for both president and vice president. Cheney campaigned against Al Gore's running mate, Joseph Lieberman, in the 2000 presidential election. While the election was undecided, the Bush-Cheney team was not eligible for public funding to plan a transition to a new administration, prompting Cheney to open a privately funded transition office in Washington. This office worked to identify candidates for all important positions in the cabinet.[99] According to Craig Unger, Cheney advocated Donald Rumsfeld for the post of Secretary of Defense to counter the influence of Colin Powell at the State Department, and tried unsuccessfully to have Paul Wolfowitz named to replace George Tenet as director of the Central Intelligence Agency.[100]

Vice presidency (2001–2009)

First term (2001–2005)

Following the September 11, 2001, attacks, Cheney remained physically apart from Bush for security reasons. For a period, Cheney stayed at a variety of undisclosed locations, out of public view.[101] Cheney later revealed in his memoir In My Time that these "undisclosed locations" included his official vice presidential residence, his home in Wyoming, and Camp David.[102] He also utilized a heavy security detail, employing a motorcade of 12 to 18 government vehicles for his daily commute from the vice presidential residence at Number One Observatory Circle to the White House.[103]

On the morning of June 29, 2002, Cheney served as acting president from 7:09 a.m. to 9:24 a.m., under the terms of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, while Bush underwent a colonoscopy.[104][105]

Iraq War

Following 9/11, Cheney was instrumental in providing a primary justification for a renewed war against Iraq. Cheney helped shape Bush's approach to the "War on Terror", making numerous public statements alleging Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction,[106] and making several personal visits to CIA headquarters, where he questioned mid-level agency analysts on their conclusions.[107] Cheney continued to allege links between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda, even though President Bush received a classified President's Daily Brief on September 21, 2001, indicating the U.S. intelligence community had no evidence linking Saddam Hussein to the September 11 attacks and that "there was scant credible evidence that Iraq had any significant collaborative ties with Al Qaeda."[108] Furthermore, in 2004, the 9/11 Commission concluded that there was no "collaborative relationship" between Iraq and al-Qaeda.[109] By 2014, Cheney continued to misleadingly claim that Saddam "had a 10-year relationship with al Qaeda".[110]

Following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Cheney remained steadfast in his support of the war, stating that it would be an "enormous success story",[111] and made many visits to the country. He often criticized war critics, calling them "opportunists" who were peddling "cynical and pernicious falsehoods" to gain political advantage while U.S. soldiers died in Iraq. In response, Senator John Kerry asserted, "It is hard to name a government official with less credibility on Iraq [than Cheney]."[112]

In a March 24, 2008, extended interview conducted in Ankara, Turkey, with ABC News correspondent Martha Raddatz on the fifth anniversary of the original U.S. military assault on Iraq, Cheney responded to a question about public opinion polls showing that Americans had lost confidence in the war by simply replying "So?"[113] This remark prompted widespread criticism, including from former Oklahoma Republican congressman Mickey Edwards, a long-time personal friend of Cheney.[114]

Second term (2005–2009)

Bush and Cheney were re-elected in the 2004 presidential election, running against John Kerry and his running mate, John Edwards. During the election, the pregnancy of his daughter Mary and her sexual orientation as a lesbian became a source of public attention for Cheney in light of the same-sex marriage debate.[115] Cheney later stated that he was in favor of gay marriages personally, but that each individual U.S. state should decide whether to permit it or not.[116] Cheney's former chief legal counsel, David Addington,[117] became his chief of staff and remained in that office until Cheney's departure from office. John P. Hannah served as Cheney's national security adviser.[118] Until his indictment and resignation[119] in 2005, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby Jr. served in both roles.[120]

On the morning of July 21, 2007, Cheney once again served as acting president, from 7:16 am to 9:21 am. Bush transferred the power of the presidency prior to undergoing a medical procedure, requiring sedation, and later resumed his powers and duties that same day.[121]

After his term began in 2001, Cheney was occasionally asked if he was interested in the Republican nomination for the 2008 presidential election. However, he always maintained that he wished to retire upon the expiration of his term and he did not run in the 2008 presidential primaries. The Republicans nominated Arizona Senator John McCain.[122]

Disclosure of documents

Cheney was a prominent member of the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPDG),[123] commonly known as the Energy Task Force, composed of energy industry representatives, including several Enron executives. After the Enron scandal, the Bush administration was accused of improper political and business ties. In July 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that the United States Department of Commerce must disclose NEPDG documents, containing references to companies that had made agreements with the previous Iraqi government to extract Iraq's petroleum.[124]

Beginning in 2003, Cheney's staff opted not to file required reports with the National Archives and Records Administration office charged with assuring that the executive branch protects classified information, nor did it allow inspection of its record keeping.[125] Cheney refused to release the documents, citing his executive privilege to deny congressional information requests.[126][127] Media outlets such as Time magazine and CBS News questioned whether Cheney had created a "fourth branch of government" that was not subject to any laws.[128] A group of historians and open-government advocates filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, asking the court to declare that Cheney's vice-presidential records are covered by the Presidential Records Act of 1978 and cannot be destroyed, taken or withheld from the public without proper review.[129][130][131][132]

CIA leak scandal

On October 18, 2005, The Washington Post reported that the vice president's office was central to the investigation of the Valerie Plame CIA leak scandal, for Cheney's former chief of staff, Lewis "Scooter" Libby, was one of the figures under investigation.[133] Libby resigned his positions as Cheney's chief of staff and assistant on national security affairs later in the month after he was indicted.[134]

In February 2006, The National Journal reported that Libby had stated before a grand jury that his superiors, including Cheney, had authorized him to disclose classified information to the press regarding intelligence on Iraq's weapons.[135] That September, Richard Armitage, former deputy secretary of state, publicly announced that he was the source of the revelation of Plame's status. Armitage said he was not a part of a conspiracy to reveal Plame's identity and did not know whether one existed.[136]

On March 6, 2007, Libby was convicted on four felony counts for obstruction of justice, perjury, and making false statements to federal investigators.[137] In his closing arguments, independent prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald said that there was "a cloud over the vice president",[138] an apparent reference to Cheney's interview with FBI agents investigating the case, which was made public in 2009.[139] Cheney lobbied President George W. Bush vigorously and unsuccessfully to grant Libby a full presidential pardon up to the day of Barack Obama's inauguration, likening Libby to a "soldier on the battlefield".[140][141] Libby was subsequently pardoned by President Donald Trump in April 2018.[142]

Assassination attempt

On February 27, 2007, at about 10 am, a suicide bomber killed 23 people and wounded 20 more outside Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan during a visit by Cheney. The Taliban claimed responsibility for the attack and declared that Cheney was its intended target. They also claimed that Osama bin Laden supervised the operation.[143] The bomb went off outside the front gate while Cheney was inside the base and half a mile away. He reported hearing the blast, saying "I heard a loud boom... The Secret Service came in and told me there had been an attack on the main gate."[144] The purpose of Cheney's visit to the region had been to press Pakistan for a united front against the Taliban.[145]

Policy formulation

Cheney has been characterized as the most powerful and influential vice president in U.S. history.[146][147] Both supporters and critics of Cheney regarded him as a shrewd and knowledgeable politician who knew the functions and intricacies of the United States federal government. A sign of Cheney's active policy-making role was then-Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert's provision of an office near the House floor for Cheney[148], in addition to his office in the West Wing,[149] his ceremonial office in the Old Executive Office Building,[150] and his Senate offices (one in the Dirksen Senate Office Building and another off the floor of the Senate).[148][151]

Cheney actively promoted an expansion of the powers of the presidency, saying that the Bush administration's "challenges to the laws which Congress passed after Vietnam and Watergate to contain and oversee the executive branch – the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the Presidential Records Act, the Freedom of Information Act and the War Powers Resolution – are 'a restoration, if you will, of the power and authority of the president.'"[152][153]

In June 2007, The Washington Post summarized Cheney's vice presidency in a Pulitzer Prize-winning[154] four-part series, based in part on interviews with former administration officials. The articles characterized Cheney not as a "shadow" president, but as someone who usually had the last words of counsel to the president on policies, which in many cases would reshape the powers of the presidency. When former vice president Dan Quayle suggested to Cheney that the office was largely ceremonial, Cheney reportedly replied, "I have a different understanding with the president." The articles described Cheney as having a secretive approach to the tools of government, indicated by the use of his own security classification and three man-sized safes in his offices.[155]

The articles described Cheney's influence on decisions pertaining to detention of suspected terrorists and the legal limits that apply to their questioning, especially what constitutes torture.[156] U.S. Army Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, who served as Colin Powell's chief of staff when he was both Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the same time Cheney was Secretary of Defense, and then later when Powell was Secretary of State, stated in an in-depth interview that Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld established an alternative program to interrogate post-9/11 detainees because of their mutual distrust of CIA.[157]

The Washington Post articles, principally written by Barton Gellman, further characterized Cheney as having the strongest influence within the administration in shaping budget and tax policy in a manner that assures "conservative orthodoxy."[158] They also highlighted Cheney's behind-the-scenes influence on the Bush administration's environmental policy to ease pollution controls for power plants, facilitate the disposal of nuclear waste, open access to federal timber resources, and avoid federal constraints on greenhouse gas emissions, among other issues. The articles characterized his approach to policy formulation as favoring business over the environment.[159]

In June 2008, Cheney allegedly attempted to block efforts by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to strike a controversial U.S. compromise deal with North Korea over the communist state's nuclear program.[160]

In July 2008, a former Environmental Protection Agency official stated publicly that Cheney's office had pushed significantly for large-scale deletions from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on the health effects of global warming "fearing the presentation by a leading health official might make it harder to avoid regulating greenhouse gases."[161] In October, when the report appeared with six pages cut from the testimony, the White House stated that the changes were made due to concerns regarding the accuracy of the science. However, according to the former senior adviser on climate change to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Stephen Johnson, Cheney's office was directly responsible for nearly half of the original testimony being deleted.[161]

In his role as President of the U.S. Senate, Cheney broke with the Bush Administration Department of Justice, and signed an amicus brief to the United States Supreme Court in the case of Heller v. District of Columbia that successfully challenged gun laws in the nation's capital on Second Amendment grounds.[162] On February 14, 2010, in an appearance on ABC's This Week, Cheney reiterated his support of waterboarding and for the torture of captured terrorist suspects, saying, "I was and remain a strong proponent of our enhanced interrogation program."[163]

Post–vice presidency

In 2008, Cheney purchased a home on Chain Bridge Road in McLean, Virginia, part of the Washington, D.C. suburbs, which he tore down for a replacement structure to be built.[164] He maintained homes in Wyoming and on Maryland's Eastern Shore as well.[165]

Political activity

In July 2012, Cheney used his Wyoming home to host a private fundraiser for Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, which netted over $4 million in contributions from attendees for Romney's campaign.[166]

Cheney was the subject of the documentary film The World According to Dick Cheney, which premiered March 15, 2013, on the Showtime television channel.[167][168][169] Cheney was also reported to be the subject of an HBO television mini-series based on Barton Gellman's 2008 book Angler[170] and the 2006 documentary The Dark Side, produced by PBS.[107]

Cheney maintained a visible public profile after leaving office,[171] being especially critical of Obama administration policies on national security.[172][173][174] In May 2009, Cheney spoke of his support for same-sex marriage, becoming one of the most prominent Republican politicians to do so. Speaking to the National Press Club, Cheney stated: "People ought to be free to enter into any kind of union they wish, any kind of arrangement they wish. I do believe, historically, the way marriage has been regulated is at a state level. It's always been a state issue, and I think that's the way it ought to be handled today."[175] In 2012, Cheney reportedly encouraged several Maryland state legislators to vote to legalize same-sex marriage in that state.[176] Although, by custom, a former vice president unofficially receives six months of protection from the United States Secret Service, President Obama reportedly extended the protection period for Cheney.[177]

On July 11, 2009, CIA director Leon Panetta told the Senate and House intelligence committees that the CIA withheld information about a secret counter-terrorism program from Congress for eight years on direct orders from Cheney. Intelligence and Congressional officials have said the unidentified program did not involve the CIA interrogation program and did not involve domestic intelligence activities. They have said the program was started by the counter-terrorism center at the CIA shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001, but never became fully operational, involving planning and some training that took place off and on from 2001 until 2009.[178] The Wall Street Journal reported, citing former intelligence officials familiar with the matter, that the program was an attempt to carry out a 2001 presidential authorization to capture or kill al Qaeda operatives.[179]

Cheney said that the Tea Party Movement was a "positive influence on the Republican Party" and that "I think it's much better to have that kind of turmoil and change in the Republican Party than it would be to have it outside."[180] In May 2016, Cheney endorsed Donald Trump as the Republican nominee in the 2016 presidential election.[181] That November, his daughter Liz won election to the House of Representatives (to his former congressional seat). When she was sworn into office in January 2017, Cheney said he believed she would do well in the position and that he would offer advice only if requested.[182] In March 2017, Cheney said that Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections could be considered "an act of war".[183]

Views on President Obama

On December 29, 2009, four days after the attempted bombing of an international passenger flight from the Netherlands to United States, Cheney criticized President Barack Obama: "[We] are at war and when President Obama pretends we aren't, it makes us less safe. ... Why doesn't he want to admit we're at war? It doesn't fit with the view of the world he brought with him to the Oval Office. It doesn't fit with what seems to be the goal of his presidency – social transformation – the restructuring of American society."[184] In response, White House communications director Dan Pfeiffer wrote on the official White House blog the following day, "[I]t is telling that Vice President Cheney and others seem to be more focused on criticizing the Administration than condemning the attackers. Unfortunately too many are engaged in the typical Washington game of pointing fingers and making political hay, instead of working together to find solutions to make our country safer."[185][186] During a February 14, 2010, appearance on ABC's This Week, Cheney reiterated his criticism of the Obama administration's policies for handling suspected terrorists, criticizing the "mindset" of treating "terror attacks against the United States as criminal acts as opposed to acts of war".[163]

In a May 2, 2011, interview with ABC News, Cheney praised the Obama administration for the covert military operation in Pakistan that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden.[187] In 2014, during an interview with Sean Hannity, he called Obama a "weak President" after Obama announced his plans to pull forces out of Afghanistan.[188]

Memoir

In August 2011, Cheney published his memoir, In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir, written with Liz Cheney. The book outlines Cheney's recollections of 9/11, the War on Terrorism, the 2001 War in Afghanistan, the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War, so-called "enhanced interrogation techniques", and other events.[189] According to Barton Gellman, the author of Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency, Cheney's book differs from publicly available records on details surrounding the NSA surveillance program.[190][191]

Exceptional: Why the World Needs a Powerful America

In 2015, Cheney published another book, Exceptional: Why the World Needs a Powerful America, again co-authored with his daughter Liz. The book traces the history of U.S. foreign policy and military successes and failures from Franklin Roosevelt's administration through the Obama administration. The authors tell the story of what they describe as the unique role the United States has played as a defender of freedom throughout the world since World War II.[192] Drawing upon the notion of American exceptionalism, the co-authors criticize Barack Obama's and former secretary of state Hillary Clinton's foreign policies, and offer what they see as the solutions needed to restore American greatness and power on the world stage in defense of freedom.[193][194]

Views on President Trump

Cheney was critical of modern Republican leadership.[195] In May 2016, Cheney said he would support Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election.[196] In May 2018, Cheney supported Trump's decision to withdraw from the Iran Nuclear Deal.[197]

Cheney criticized the Trump administration at the American Enterprise Institute World Forum alongside Vice President Mike Pence in March 2019. Questioning his successor on Trump's commitment to NATO and tendency to announce policy decisions on Twitter before consulting senior staff members, Cheney commented, "It seems, at times, as though your administration’s approach has more in common with Obama’s foreign policy than traditional Republican foreign policy."[198]

On the one-year anniversary of the 2021 United States Capitol attack, Cheney joined his daughter Liz Cheney at the Capitol and participated in the remembrance events.[199] His daughter was the only Republican member of Congress to attend the events, despite the events being open for attendance by all others.[200] He later appeared in a 2022 primary campaign ad for Liz in which he called Trump a "coward" and a "threat to our republic" due to his attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election. That year, Liz ran for her Wyoming congressional seat against Trump-backed primary challenger Harriet Hageman, who ultimately won by over 30%.[201][202]

On September 6, 2024, Cheney released a public statement confirming that he intended to cast his vote in the 2024 presidential election for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris. The previous day, his daughter Liz had told a crowd of Cheney's intention to do so.[203] In his statement, Cheney opined

Public perception and legacy

Cheney's early public opinion polls were more favorable than unfavorable, reaching his peak approval rating in the wake of the September 11 attacks at 68 percent.[16] However, polling numbers for both he and the president gradually declined in their second terms,[16][206] with Cheney reaching his lowest point shortly before leaving office at 13 percent.[206][207] Cheney's Gallup poll figures are mostly consistent with those from other polls:[16][208]

- April 2001 – 63% approval, 21% disapproval

- January 2002 – 68% approval, 18% disapproval

- January 2004 – 56% approval, 36% disapproval

- January 2005 – 50% approval, 40% disapproval

- January 2006 – 41% approval, 46% disapproval

- July 2007 – 30% approval, 60% disapproval

- March 2009 – 30% approval, 63% disapproval

In April 2007, Cheney was awarded an honorary doctorate of public service by Brigham Young University, where he delivered the commencement address.[209] His selection as commencement speaker was controversial. The college board of trustees issued a statement explaining that the invitation should be viewed "as one extended to someone holding the high office of vice president of the United States rather than to a partisan political figure".[210] BYU permitted a protest to occur so long as it did not "make personal attacks against Cheney, attack (the) BYU administration, the church or the First Presidency".[211]

Cheney is considered by many sources to have been the most powerful vice president in American history.[4][5][212] In its obituary of Cheney, The New York Times described him as such, and cited him as President Bush's "most influential White House adviser in an era of terrorism, war and economic change".[19] USA Today noted that Cheney was the "chief architect of the war in Iraq" and one of the last figures of the "old Republican Party guard".[213] The BBC called Cheney "the ultimate Washington insider" who helped shape the foreign policy powers of the presidency.[18] According to Al Jazeera, he fought intensely for an expansion of the president's power, which he felt had been eroding since Watergate, and increased the vice president's clout by putting together a national security team that often served as a power center within the George W. Bush administration.[214] He was noted for expanding the powers of the vice presidency and having "built unrivalled authority and influence."[215] Cheney was additionally noted for having transformed the once-mundane role of the vice presidency into a "U.S. version of the office of prime minister, subordinate to, but almost coequal of, the presidency itself".[215] Cheney had a "commanding [hand], in implementing decisions most important to [President Bush] and some of surpassing interest to himself".[216]

Cheney "wielded rare clout in Washington for over three decades," but received negative and controversial reception globally, primarily for the role he played in the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, his promotion of the existence of evidently non-existent weapons of mass destruction as a casus belli for the former conflict, and the promotion and supervision of the increased use of torture against citizens and foreign nationals at Guantanamo Bay and other U.S. detention facilities worldwide.[19][212]

As a result of Cheney's admittance that he signed off on the use of "enhanced interrogation techniques,"[217][218] some public officials, media outlets, and advocacy groups had called for his prosecution under various anti-torture and war crimes statutes.[219][220] French newspaper Le Monde described Cheney as the "father" of the invasion of Iraq who "embodied the excesses of the war on terror".[221] Jon Meacham's book Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush, published in November 2015, describes Bush as being simultaneously laudatory and critical of the former vice president, with Bush describing him as "having his own empire" and being "very hard-line."[222]

In popular culture

- In Eminem's 2002 single "Without Me", where the lines "I know that you got a job, Ms. Cheney / But your husband's heart problem's complicated" refer to his health problems.[223]

- In The Day After Tomorrow, the character Raymond Becker (played by Kenneth Welsh) is intended to be a caricature of Dick Cheney.[224]

- In W. (2008), a biographical comedy-drama film directed by Oliver Stone, he is portrayed by Richard Dreyfuss.[225]

- In War Dogs (2016), where the line "God bless Dick Cheney's America" refers to his support of American military presence in Iraq.[226]

- In Who Is America? (2018), a political satire series, Sacha Baron Cohen pranked Cheney into signing a makeshift waterboard kit.[227]

- In Vice (2018), a biographical comedy-drama film written and directed by Adam McKay, Cheney is portrayed by Christian Bale,[228] for which the latter won a Golden Globe Award[229] and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[230]

- In Mrs. America (2020), a historical drama television miniseries produced by FX, Cheney is portrayed by Andrew Hodwitz.[231]

- Bob Rivers did a parody cover called "Cheney's Got a Gun"[232]

- Cheney has been compared to Darth Vader, a characterization originated by his critics, but which was later adopted humorously by Cheney himself as well as by members of his family and staff.[233]

Personal life

Cheney was a member of the United Methodist Church[234] and was the first Methodist vice president to serve under a Methodist president.[235] His brother, Bob, is a former civil servant at the Bureau of Land Management.[236]

His wife, Lynne, was chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities from 1986 to 1996. She is a public speaker, author, and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.[237] They had two daughters, Elizabeth ("Liz") and Mary Cheney, and seven grandchildren. Liz, a former congresswoman from Wyoming, is married to Philip Perry, a former general counsel of the Department of Homeland Security. Mary, a former employee of the Colorado Rockies baseball team and the Coors Brewing Company, was a campaign aide to the Bush re-election campaign; she lives in Great Falls, Virginia, with her wife Heather Poe.[238] Cheney publicly supported gay marriage after leaving the vice presidency.[239]

Health problems

Cheney's long histories of cardiovascular disease and periodic need for urgent health care raised questions of whether he was medically fit to serve in public office.[240] Having smoked approximately three packs of cigarettes per day for nearly 20 years,[241] Cheney had his first of five heart attacks on June 18, 1978,[242] at age 37. Subsequent heart attacks in 1984, 1988, 2000, and 2010 resulted in the moderate contractile dysfunction of his left ventricle.[243] He underwent four-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting in 1988, coronary artery stenting in November 2000, urgent coronary balloon angioplasty in March 2001, and the implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in June 2001.[244]

On September 24, 2005, Cheney underwent a six-hour endo-vascular procedure to repair popliteal artery aneurysms bilaterally, a catheter treatment technique used in the artery behind each knee.[245] The condition was discovered at a regular physical in July, and was not life-threatening.[246] Cheney was hospitalized for tests after experiencing shortness of breath five months later. In late April 2006, an ultrasound revealed that the clot was smaller.[245]

On March 5, 2007, Cheney was treated for deep vein thrombosis in his left leg at George Washington University Hospital after experiencing pain in his left calf. Doctors prescribed blood-thinning medication and allowed him to return to work.[247] CBS News reported that during the morning of November 26, 2007, Cheney was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and underwent treatment that afternoon.[245] On July 12, 2008, Cheney underwent a cardiological exam; doctors reported that his heartbeat was normal for a 67-year-old man with a history of heart problems. As part of his annual checkup, he was administered an electrocardiogram and radiological imaging of the stents placed in the arteries behind his knees in 2005. Doctors said that Cheney had not experienced any recurrence of atrial fibrillation and that his special pacemaker had neither detected nor treated any arrhythmia.[248] On October 15, 2008, Cheney returned to the hospital briefly to treat a minor irregularity.[249]

On January 19, 2009, Cheney strained his back "while moving boxes into his new house," according to a White House statement. As a consequence, he was in a wheelchair for two days, including his attendance at the 2009 United States presidential inauguration.[250][251] On February 22, 2010, Cheney was admitted to George Washington University Hospital after experiencing chest pains. A spokesperson later said Cheney had experienced a mild heart attack after doctors had run tests.[252] On June 25, 2010, Cheney was admitted to George Washington University Hospital after reporting discomfort.[253]

In early-July 2010, Cheney was outfitted with a left-ventricular assist device (LVAD) at Inova Fairfax Heart and Vascular Institute to compensate for worsening congestive heart failure.[254] The device pumped blood continuously through his body.[255][256] He was released from Inova on August 9, 2010,[257] and had to decide whether to seek a full heart transplant.[258][259] This pump was centrifugal and as a result he remained alive without a pulse for nearly fifteen months.[260]

On March 24, 2012, Cheney underwent a seven-hour heart transplant procedure at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Woodburn, Virginia. He had been on a waiting list for more than 20 months before receiving the heart from an anonymous donor.[261][262] Cheney's principal cardiologist, Jonathan Reiner, advised his patient that "it would not be unreasonable for an otherwise healthy 71-year-old man to expect to live another 10 years" with a transplant, saying in a family-authorized interview that he considered Cheney to be otherwise healthy.[263]

Hunting incident

On February 11, 2006, Cheney accidentally shot Harry Whittington, a then-78-year-old Texas attorney, while participating in a quail hunt at Armstrong ranch in Kenedy County, Texas.[264] Secret Service agents and medical aides, who were traveling with Cheney, came to Whittington's assistance and treated his birdshot wounds to his right cheek, neck, and chest. An ambulance standing by for the Vice President took Whittington to nearby Kingsville before he was flown by helicopter to Corpus Christi Memorial Hospital. On February 14, 2006, Whittington had a non-fatal heart attack and atrial fibrillation due to at least one lead-shot pellet lodged in or near his heart.[265] Because of the small size of the birdshot pellets, doctors decided to leave as many as 30 pieces of the pellets lodged in his body rather than try to remove them.[266]

The Secret Service stated that they notified the sheriff about one hour after the shooting. Kenedy County Sheriff Ramone Salinas III stated that he first heard of the shooting at about 5:30 p.m.[267] The next day, ranch owner Katharine Armstrong informed the Corpus Christi Caller-Times of the shooting.[268] Cheney had a televised interview with MSNBC News about the shooting on February 15. Both Cheney and Whittington called the incident an accident. Early reports indicated that Cheney and Whittington were friends and that the injuries were minor. Whittington later told The Washington Post that he and Cheney were not close friends but acquaintances. When asked if Cheney had apologized, Whittington declined to answer.[269]

The sheriff's office released a report on the shooting on February 16, 2006, and witness statements on February 22, indicating that the shooting occurred on a clear sunny day, and Whittington was shot from 30 or 40 yards (30 or 40 m) away while searching for a downed bird. Armstrong, the ranch owner, claimed that all in the hunting party were wearing blaze-orange safety gear and none had been drinking.[270] However, Cheney acknowledged that he had had one beer four or five hours prior to the shooting.[271] Although Kenedy County Sheriff's Office documents support the official story by Cheney and his party, re-creations of the incident produced by George Gongora and John Metz of the Corpus Christi Caller-Times indicated that the actual shooting distance was closer than the 30 yards claimed.[272]

The incident hurt Cheney's popularity standing in the polls.[273] According to polls on February 27, 2006, two weeks after the accident, Cheney's approval rating had dropped 5 percentage points to 18%.[274] The incident became the subject of a number of jokes and satire.[275]

Death

Cheney died in Northern Virginia on the evening of November 3, 2025, at the age of 84.[18][19] He had been experiencing complications related to pneumonia and vascular disease.[20]

Following Cheney's death, former president George W. Bush issued a statement praising Cheney as "among the finest public servants of his generation – a patriot who brought integrity, high intelligence, and seriousness of purpose to every position he held".[276] Former presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden also issued statements honoring Cheney.[277][278][279] Former vice presidents Mike Pence and Kamala Harris released statements following Cheney's death.[279] Vice President JD Vance and President Donald Trump did not issue a statement after his death was announced.[279][280] However, U.S. flags at the White House were lowered in Cheney's honor on the day of his death.[281] After being questioned about Trump's lack of a comment regarding Cheney's death, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt stated that Trump was "aware" that Cheney had died without elaborating any further.[282] Online, some notable figures denounced Cheney as a mass murderer and war criminal who faced no prosecution while alive.[283][284]

Senate majority leader John Thune said that the Republican leadership was reviewing the possibility of having Cheney lying in state at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.[285]

Works

- Clausen, Aage R.; Cheney, Richard B. (March 1970). "A Comparative Analysis of Senate–House Voting on Economic and Welfare Policy, 1953–1964*". American Political Science Review. 64 (1): 138–152. doi:10.2307/1955618. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1955618. S2CID 154337342. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017 – via Cambridge Core.

- Cheney, Richard B.; Cheney, Lynne V. (1983). Kings of the Hill: Power and Personality in the House of Representatives. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-0230-5.

- Cheney, Dick (1997). Professional Military Education: An Asset for Peace and Progress. Directed and edited by Bill Taylor. Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic & International Studies. ISBN 0-89206-297-5. OCLC 36929146.

- Cheney, Dick; et al. (with Liz Cheney) (2011). In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir. New York: Threshold Editions. ISBN 978-1-4391-7619-1.

- Cheney, Dick; Reiner, Jonathan; et al. (with Liz Cheney) (2013). Heart: An American Medical Odyssey. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4767-2539-0.

- Cheney, Dick; Cheney, Liz (2015). Exceptional: Why the World Needs a Powerful America. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-1541-7.

Notes

References

- "CNN Transcript – Special Event: Cheney Holds News Briefing with Republican House Leaders – December 5, 2000". transcripts.cnn.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016.

- "How Dick Cheney Plans to Use His Daughter Liz's Political Future to Ensure His Legacy". New York Magazine. March 5, 2010. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019.

- Alliance for a Strong America Commercial, 2014 on YouTube

- "Cheney: A VP With Unprecedented Power". NPR. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Reynolds, Paul (October 29, 2006). "The most powerful vice-president ever?". United Kingdom: BBC News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Page, Joey Garrison and Susan. "Dick Cheney, powerful VP who pushed Iraq invasion, dies at 84. Live updates". USA TODAY.

- Cheney: The Untold Story of America's Most Powerful and Controversial Vice President, p. 11

- "Richard B. Cheney – George H. W. Bush Administration". Historical Office. Office of the Secretary of Defense – Historical Office. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "Prewar Iraq Intelligence: A Look at the Facts". NPR.org. NPR. November 23, 2005. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Shane, Scott; Lichtblau, Eric (May 14, 2006). "Cheney Pushed U.S. to Widen Eavesdropping". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- "Cheney offended by Amnesty criticism; Rights group accuses U.S. of violations at Guantanamo Bay". CNN. May 21, 2005. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Rosenberg, Carol (December 4, 2019). "What the C.I.A.'s Torture Program Looked Like to the Tortured". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- "Cheney at odds with Bush on gay marriage – politics". NBC News. August 25, 2004. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Kaufman, Marc and Allen, Mike. "Cheney splits with Bush on gay marriage ban", The Washington Post via The Boston Globe (August 25, 2004).

- Friedersdorf, Conor (August 30, 2011). "Remembering Why Americans Loathe Dick Cheney". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- Carroll, Joseph (July 18, 2007). "Americans' Ratings of Dick Cheney Reach New Lows". The Gallup Organization. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- Lebowitz, Megan (September 7, 2024). "Former Vice President Dick Cheney says he will vote for Harris". NBC News. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- "Former US Vice-President Dick Cheney dies aged 84". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2025. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- McFadden, Robert D. (November 4, 2025). "Dick Cheney, Powerful Vice President and Washington Insider, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- Collinson, Stephen; Stracqualursi, Veronica (November 4, 2025). "Dick Cheney, influential Republican vice president to George W. Bush, dies". CNN. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- "Interview With Lynne Cheney". CNN. September 20, 2003. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- "Bio on Kids' section of White House site". White House. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- "Calvert Profile" (PDF). Lincoln Public Schools. May 15, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2006. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- "Official US Biography". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2006 – via National Archives.

- "Dick Cheney Fast Facts". CNN. September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2025.

- "In Wyoming, Likely End of Cheney Dynasty Will Close a Political Era (Published 2022)". August 15, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2025.

- Cheney, Dick, with Liz Cheney. In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir, pp. 26–28. Simon and Schuster, 2011. [ISBN missing]

- Kaiser, Robert G. (August 29, 2011). "Review: In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir by Dick Cheney". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- Martin, Douglas (January 27, 2008). "H. Bradford Westerfield, 79, Influential Yale Professor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- "A Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Department" (PDF). North Hall News. University of Wisconsin–Madison: 4. Fall 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- McCollough, Lindsay G. (Producer); Gellman, Barton (Narrator). The Life and Career of Dick Cheney. The Washington Post (Narrated slideshow). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- Lemann, Nicholas (May 7, 2001). "The Quiet Man". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 18, 2004. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- Carney, James (December 30, 2002). "7 Clues To Understanding Dick Cheney". TIME Magazine. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- "Profile of Dick Cheney". ABC News. January 6, 2006. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- Noah, Timothy (March 18, 2004). "How Dick Cheney dodged the draft". Slate. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- Seelye, Katharine Q. (May 1, 2004). "Cheney's Five Draft Deferments During the Vietnam Era Emerge as a Campaign Issue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- "Dick Cheney Fast Facts". CNN. September 21, 2013. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Lowell Bergman; Marlena Telvick (February 13, 2007). "Dick Cheney's Memos from 30 Years Ago". Frontline: News War. Public Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- Taibbi, Matt (April 2, 2007). "Cheney's Nemesis". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 19, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Photographs – Richard Cheney as an Assistant to President Ford". www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- "Richard Cheney as an Assistant to President Ford". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum. August 26, 2002. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- "New Aide to Ford Rumsfeld Protege". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "People in the News: Dick Cheney". Chiff.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2005. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- "Dick Cheney, Wyoming oilman and former vice president, dies at 84". Wyofile. November 4, 2025. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- "The Board of Regents". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- "Richard B. Cheney: 17th Secretary of Defense". United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on April 1, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Dick Cheney on Education". On the Issues. Archived from the original on September 18, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- McIntyre, Robert S. (July 28, 2000). "Dick Cheney, Fiscal Conservative?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- Saira Anees (April 4, 2008). "The Complicated History of John McCain and MLK Day". ABC. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

Dick Cheney...voted for the holiday. (Cheney had voted against it in 1978.)

- Jonathan Martin. "A political junkie's guide to Dick Cheney's memoir". Politico. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- "Reagan gains backing of 36 House Republicans". Associated Press. p. 10.[permanent dead link]

- Booker, Salih (2001). "The Coming Apathy: Africa Policy Under a Bush Administration". Archived from the original on September 18, 2004. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- "Defending Liberty in a Global Economy". Cato Institute. June 23, 1998. Archived from the original on September 18, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- Rosenbaum, David E. (July 28, 2000). "Cheney Slips in Explaining A Vote on Freeing Mandela". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 18, 2004. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- "Cheney defends voting record, blasts Clinton on talk-show circuit". CNN. July 30, 2000. Archived from the original on April 2, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- "The Times-News". July 11, 2012. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019 – via Google News Archive Search.

- Sean Wilintz (July 9, 2007). "Mr. Cheney's Minority Report". The New York Times. Princeton, New Jersey. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014.

- "Calm After Desert Storm". Hoover Institution. Summer 1993. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- Taggart, Charles Johnson (1990). "Cheney, Richard Bruce". 1990 Britannica Book of the Year. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 85. ISBN 0-85229-522-7.

- "Jefferson Awards Foundation". Jeffersonawards.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- "Vice President Dick Cheney: Personal Reflections on his Public Life". YouTube. Conversations with Bill Kristol. October 12, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- "Dick Cheney on Conversations with Bill Kristol". Conversationswithbillkristol.org. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.