Confucius - A00072

"By three methods may we learn wisdom; first, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third, by experience, which is bitterest." (03/21/2022)

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

| |

|---|---|

孔子 | |

| |

| Born | Kong Qiu c. 551 BCE |

| Died | c. 479 BCE (aged 71–72) Si River, Lu |

| Resting place | Cemetery of Confucius, Lu |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Confucianism |

| Notable students | |

Main interests |

|

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Confucius (born 551, Qufu, state of Lu [now in Shandong province, China]—died 479 bce, Lu) was China’s most famous teacher, philosopher, and political theorist, whose ideas have profoundly influenced the civilizations of China and other East Asian countries.

Life of Confucius

Confucius was born near the end of an era known in Chinese history as the Spring and Autumn Period (770–481 BCE). His home was in Lu, a regional state of eastern China in what is now central and southwestern Shandong province. Like other regional states at the time, Lu was bound to the imperial court of the Zhou dynasty (1045–221 BCE) through history, culture, family ties (which stretched back to the dynasty’s founding, when relatives of the Zhou rulers were enfeoffed as heads of the regional states), and moral obligations. According to some reports, Confucius’s early ancestors were the Kongs from the state of Song—an aristocratic family that produced several eminent counselors for the Song rulers. By the mid-7th century BCE, however, the family had lost political standing and most of its wealth, and some of the Kongs—Confucius’s great-grandfather being one—had relocated to the state of Lu.

The Kongs of Lu were common gentlemen (shi) with none of the hereditary entitlements their ancestors had once enjoyed in Song. The common gentlemen of the late Zhou dynasty could boast of their employability in the army or in any administrative position—because they were educated in the six arts of ritual (see below Teachings of Confucius), music, archery, charioteering, writing, and arithmetic—but in the social hierarchy of the time they were just a notch higher than the common folk. Confucius’s father, Shu-liang He, had been a warrior and served as a district steward in Lu, but he was already an old man when Confucius was born. A previous marriage had given him nine daughters and a clubfooted son, and so it was with Confucius that he was finally granted a healthy heir. But Shu-liang He died soon after Confucius’s birth, leaving his young widow to fend for herself.

Confucius was candid about his family background. He said that, because he was “poor and from a lowly station,” he could not enter government service as easily as young men from prominent families and so had to become “skilled in many menial things” (Analects [Lunyu], 9:6). He found employment first with the Jisun clan, a hereditary family whose principal members had for many decades served as chief counselors to the rulers of Lu. A series of modest positions with the Jisuns—as keeper of granaries and livestock and as district officer in the family’s feudal domain—led to more important appointments in the Lu government, first as minister of works and then as minister of crime.

Records of the time suggest that, as minister of crime, Confucius was effective in handling problems of law and order but was even more impressive in diplomatic assignments. He always made sure that the ruler and his mission were well prepared for the unexpected and for situations that might put them in harm’s way; he also knew how to advise them to bring a difficult negotiation to a successful conclusion. Yet he held his office for only a few years. His resignation was the result of a protracted struggle with the hereditary families—which, for generations, had been trying to wrestle power away from the legitimate rulers of Lu. Confucius found the actions of the families transgressive and their ritual indiscretions objectionable, and he was willing to fight by fair means or foul to have the power of the ruler restored. A major clash took place in 498 BCE. A plan to steer the families toward self-ruin backfired. The heads of the families suspected Confucius, and so he had no choice but to leave his position and his home.

The self-exile took Confucius on a long journey: first to Wei, the state just west of Lu, then southward to the state of Song, and finally to the states of Chen and Cai. The journey lasted 14 years, and Confucius spent much of that time looking for rulers who might be willing to accept his influence and be guided by his vision of virtuous government. Although his search was ultimately in vain, he never gave up, because he was eager for someone to “put me to use” (Analects, 17:5). He said to those who found his ambitions suspect, “How can I be like a bitter gourd that hangs from the end of a string and can not be eaten?” (Analects, 17:7).

Confucius was emboldened to think that he could set things right in the world, because he was born at a time when such aspirations were within the reach of men living in circumstances similar to his. By the mid-6th century BCE the Zhou dynasty was approaching its 500th year. The political framework that the dynastic founders had put in place—an enfeoffment system held together by family ties—was still standing, but the joints had been giving out since the beginning of the Spring and Autumn Period, and so the structure, if not shored up, was in danger of collapse. The regional rulers, who were relatives of the Zhou king, should have been his strongest supporters, but they preferred to pursue their own ambitions. In the century before Confucius’s birth, two or three of them simply acted on behalf of the king, and under their watch the empire managed to hold itself together and to keep enemies at bay. By Confucius’s time, however, such leaders had disappeared. No one among the regional rulers was interested in the security of the empire or the idea of the greater good. Petty feuds for petty gains consumed most of their time, while lethargy took up the rest. The same could be said of the members of the aristocratic class, who had once aided their ruler in government. Now they were gaining the upper hand, and some were so brazen as to openly compete with their ruler for wealth and women. Their apathy and ineptitude, however, allowed the common gentlemen—men like Confucius, who had once been in their service—to step in and take charge of the administrative functions of the government.

The common gentlemen, at this point, still could not displace the aristocrats as the society’s elite. Yet, if they worked hard enough and were smart, they could exert influence in most political contests. But the more discerning among them set their goals higher. They saw an opportunity to introduce a few new ideas about worth (xian) and nobleness (shang)—which, they felt, could challenge assumptions that had been used to justify the existing social hierarchy. They asked whether ability and strength of character should be the measures of a person’s worth and whether men of noble rank should be stripped of their titles and privileges for incompetence and moral indiscretion. Those who posed such questions were not merely seeking to compete in the political world. They wanted to change unspoken rules so as to favour the virtuous and the competent. This, in part, explains what Confucius was trying to teach. He believed that the moral resolve of a few could have a beneficial effect on the fate of the many. But integrity alone, in his view, would not be enough. Good men had to be tested in politics: they should equip themselves with knowledge and skills, serve their rulers well, and prove their worth through their moral influence.

The man Confucius looked back to for inspiration and guidance was Zhougong (the Duke of Zhou)—a brother of the founder of the Zhou dynasty and the regent of the king’s young son Chengwang. Despite the temporal distance between them, Confucius believed that he and the Duke of Zhou wanted the same thing for the dynasty: social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations, with minimal resort to legal rules. But the Duke of Zhou was royalty and Confucius was a professional bureaucrat, which meant that he had limited political authority. And even the authority he possessed was transient, depending on whether he had a government job. Without an official position, Confucius also would not be entitled (for example) to host a feast, to assist a ruler in a sacrifice, or to take part in any of the occasions that were the living components of the political order that the Duke of Zhou had envisioned and Confucius strongly endorsed. Thus, Confucius was distressed when he was unemployed—anxious about not being of use to the world and about not having material support. Men who knew him on his travels wondered whether his eagerness for a political position might have led him to overplay his hand and whether he had compromised his principles by allowing disreputable men and women to act as his intermediaries. His critics included the three or four of his disciples who accompanied him on his exile.

Confucius’s disciples were considerably younger than him. He did not actively recruit them when he was a counselor in Lu. He did not found any school or academy. Young men from a wide range of backgrounds—sons of aristocrats, children of common gentlemen, merchants, farmers, artisans, and even criminals and sons of criminals—chose to attach themselves to him in order to learn from him skills that might get them started on a path toward an official career. In the process, they acquired a lot more: in particular, a gentleman’s refinement and moral acuity, which in Confucius’s mind were essential to a political profession. Confucius was the “master” (zi) to these followers, who called themselves his “disciples” or “apprentices” (tu). Among his earliest disciples, three stood out: Zigong, Zilu, and Yan Hui.

Zigong had been a merchant before becoming Confucius’s disciple. He was articulate and shrewd and quick on his feet. Confucius observed in him a resolve to improve his lot and the promise of becoming a fine diplomat or a financial manager. He enjoyed Zigong’s company because Zigong was someone with whom he could share his thoughts about the world and the people they knew and about poetry and ritual practices (Analects, 11:3; 1:15; 11:19; 5:9).

Zilu, unlike Zigong, was rough and unhewn, a rustic man. Confucius knew that Zilu would do anything to protect him from harm: “wrestle a tiger with his bare hands” or “follow him on the open sea in a bamboo raft.” Yet, Confucius felt, simply being brave and loyal was “hardly the way to be good,” because, without the advantage of thought and a love for learning, people would not be able to know whether their judgment had been misguided or whether their actions might lead them and others onto a perilous road, if not a violent end (Analects, 5:7; 7:11). Still, Confucius took Zilu in, for he was someone “who did not feel ashamed standing next to a man wearing fox or badger fur while himself dressed in a tattered gown padded with silk floss” and who was so reliable that “by speaking from just one side of a dispute” in a court of law he could “bring a legal dispute to a conclusion” (Analects, 9:27; 12:12). Besides, Confucius did not deny instruction to anyone who wanted to learn and was unwilling to give up when trying to solve a difficult problem. In return, he expected nothing more than a bundle of dried meat as a gift (Analects, 7:7).

Yet even that modest offer was probably beyond the means of another disciple, Yan Hui, who was from a poor family and who was content with “living in a shabby neighborhood on a bowlful of millet and a ladleful of water” (Analects, 6:11). No hardship or privation could have distracted him from his love of learning and his desire to know the good. Yan Hui was Confucius’s favourite, and, when he died before his time, Confucius was so bereft that other disciples wondered whether such a display of emotion was appropriate. To this their teacher responded, “If not for this man, for whom should I show so much sorrow?” (Analects, 11:9; 11:10).

It was these three—Zigong, Zilu, and Yan Hui—who followed Confucius on his long journey into the unknown. In doing so, they left behind not only their homes and families but also career opportunities in Lu that could have been gainful.

Their first stop was the state of Wei. Zilu had relatives there who could have introduced Confucius to the state’s ruler. There were others, too—powerful men in the ruler’s service—who knew of Confucius’s reputation and were willing to help him. But none of these connections landed Confucius a job. Part of the problem was Confucius himself: he was unwilling to pursue any avenues that might obligate him to those who could bring him trouble rather than aid. Also, the ruler of Wei was not interested in finding a capable man who could offer him counsel. Moreover, he had plenty of distractions—conflicts with neighbouring states and at home in Wei—to fill his time. Still, Confucius was patient, waiting four years before he was granted an audience. But the meeting was disappointing: it only confirmed what Confucius already knew about this man’s character and judgment. Soon after their encounter, the ruler died, and Confucius saw no further reason to remain in Wei. Thus, he headed south with his disciples.

Before reaching the state of Chen, his next stop, two incidents along the road nearly took his life. In one, a military officer, Huan Tui, tried to ambush Confucius as he was passing through the state of Song. In another, he was surrounded by a mob in the town of Kuang, and for a time it looked as though he might be killed. These incidents were not spontaneous but were the machinations of Confucius’s enemies. But who would have wanted him dead, and what could he have done to provoke such reactions? Historians in later eras speculated about the causes and resolutions of these crises. Although they never found an adequate explanation for Huan Tui’s action, some suggested that the mob of Kuang mistook Confucius for someone else. In any event, the Analects, the most reliable source on Confucius’s life, records only what Confucius said at those moments when he realized that death might be imminent. “Heaven has given me this power—this virtue. What can Huan Tui do to me!” was his response after he learned about Huan Tui’s plan to ambush him (Analects, 7:23). His utterance at the siege of Kuang conveyed even greater confidence that Heaven would stand by him. He said that with the founder of the Zhou dynasty dead, this man’s cultural vestiges “are invested in me.” And since “Heaven has not destroyed this culture” and does not intend to do so, it will look after the cultural heirs of the Zhou. Thus, Confucius declaimed, “What can the people of Kuang do to me?” (Analects, 9:5).

Emboldened by his purpose, Confucius continued his journey to Chen, where he spent three uneventful years. Eventually, a major war between Chen and a neighbouring state led him to journey west toward the state of Chu, not knowing that another kind of trial was awaiting him. This time, “the provisions ran out,” and “his followers became so weak that none of them could rise up on their feet” (Analects 15:2). The brief account in this record prompted writers in later centuries to speculate about how Confucius might have behaved in this situation. Was he calm or vexed? How did he talk to his disciples? How did he help them come to terms with their predicament? And which disciple understood him best and offered him solace? None of these stories could claim veracity, but, taken together, they humanized the characters involved and filled, if only imaginatively, the gaps in the historical sources.

Confucius and his companions went only as far as a border town of Chu before they decided to turn back and retrace their steps, first to Chen and then to Wei. The journey took more than three years, and, after reaching Wei, Confucius stayed there for another two years. Meanwhile, two of his disciples, Zigong and Ran Qiu, decided to leave Confucius in Wei and accept employment in the government of Lu. At once Zigong proved his talent in diplomacy, and Ran Qiu did the same in warfare. It was probably these two men who approached the ruler and the chief counselor of Lu, asking them to make a generous offer to Confucius to entice him back. Their plan worked. The Zuozhuan (“Zuo Commentary”), an early source on the history of this period (see below Classic works), notes that, in the 11th year of the reign of Duke Ai of Lu (484 BCE), a summons from the duke arrived along with a gift of a handsome sum. “Thereupon, Confucius returned home.”

After his return, Confucius did not seek any position in the Lu government. He did not have to. The present ruler and his counselors regarded him as the “state’s elder” (guolao). They either approached him directly for advice or used his disciples as intermediaries. The number of his disciples multiplied. The success of Zigong and Ran Qiu must have enhanced his reputation as a person who could prepare young men for political careers. But those who were drawn to him for this reason often found themselves becoming interested in questions other than how to advance in the world (Analects, 2:18). Some asked about the idea of virtue, about the moral requisites for serving in government, or about the meanings of phrases such as “keen perception” and “clouded judgment” (Analects, 12:6; 12:10). Others wanted to know how to pursue knowledge and how to read abstruse texts for insights (Analects, 3:8). Confucius tried to answer these questions as best as he could, but his responses could vary depending on the temperament of the interlocutor, leading to confusion among his students when they tried to compare notes (Analects, 11:22). This way of instructing was wholly in tune with what Confucius believed to be the role of a teacher. A teacher could only “point out one corner of a square,” he said; it was up to the students “to come back with the other three” (Analects, 7:8). To teach, therefore, is “to impart light” (hui): to provide guidance to students and to entice them forward, so that even when they are tired and dispirited, even when they want to give up, they cannot. In a similar vein, Confucius said of himself, “I am the sort of man who forgets to eat when trying to solve a problem, who is so joyful that I forget my worries and do not become aware of the onset of old age” (Analects, 7:19).

When old age did arrive, Confucius discovered that the act of holding his conduct and judgment to the right measure no longer bore him down. “At 70,” he said, “I followed what my heart desired without overstepping the line” (Analects, 2:4). This, however, did not mean that Confucius was free of care. Historians and philosophers in later centuries typically portrayed a careworn Confucius in his final days. Yet he still rejoiced in life because life astonished him, and the will in all living things to carry on in spite of setbacks and afflictions inspired him. It was the pine and the cypress Confucius admired most, because “they are the last to lose their needles” (Analects, 9:28). He died at the age of 73 on the 11th day of the fourth lunar month in the year 479 BCE.

Sources on Confucius

Sources on the life of Confucius are sparse. Official annals and other historical sources of the late Spring and Autumn Period rarely mention his name because he did not play a conspicuous role in the political world. In fact, he barely existed in that world, since most of his life was spent either in preparation for such a career or in exile. Yet the gaps in the historical records were eventually beneficial, because they prompted later scholars to look for any trace of evidence that might reveal something new about him. Unfortunately, such searches often led to imaginative conjectures about Confucius, as in the account by a writer of the 3rd century BCE in which Confucius described himself as a yellow chi (homeless dragon) swimming in the turbid water but drinking from the clear. Confucius could have chosen to live like a true dragon and never leave his pristine pool, but he preferred to be a chi. Throughout early Chinese history, there were many such writers, and the source they turned to repeatedly for understanding and inspiration was the Analects.

The Analects is the work most closely associated with Confucius. It is a record of his life in fragments, collected into 20 sections. The sections contain descriptions of his character, deportment, and moments of his life in exile or at home in Lu; bits of conversations he had with his disciples and other people he knew; and remarks spoken in his voice but often in the absence of a context. Without the aid of commentaries, this work—which also lacks any apparent organization—can be misleading or discouraging for some readers. Yet, with patience and attentiveness, it is possible to glean from the gathered pieces flashes of Confucius’s genius and the elements of his humanity. The Analects probably took shape within the first century after Confucius’s death. A handful of younger disciples—who make their appearances rather forcefully at the beginning and the end of the work—could have initiated the project, but it took another 200–300 years of tinkering—with some passages being omitted and others appended or modified—before the text settled into its present form. Material evidence of the age of the standard text emerged from the ground in 1973, when archaeologists opened the tomb of the prince of Zhongshan (Liu Xiu, also known as King Huai), a relative of the Han emperor Wudi. The tomb, dated to 55 BCE, was discovered in Hebei province about 100 miles south of Beijing. The Analects, written on bamboo strips, was included among the grave objects that accompanied the prince to his afterlife.

A second work that is central to the study of Confucius and his thought is the Zuo Zhuan (“Zuo Commentary”). Although it is a commentary on the Chunqiu, the official annals of the state of Lu covering the Spring and Autumn Period, it does more than provide background and narrative structure for the events listed chronologically in the annals. The Zuo writer probably had at his disposal a wide range of scribal records, the most important of which were speeches of rulers and counselors and of men and women who had played a role in the political fate of their families and their states during the late Zhou dynasty. The best of these speeches reflect the characters of the speakers and the cultural practices that guided their moral decision making. They also throw light on Confucius’s intellectual ancestry and the roots of his moral thinking. Confucius never professed to be an original thinker. He said, “I transmit but do not innovate. I love antiquity and have faith in it” (Analects, 7:1). The Zuo Zhuan offers a view of China in the 200 years before Confucius’s birth, which was not the antiquity Confucius had in mind. But when one reads it together with the early classics on rites (see below Teachings of Confucius), poetry, and history, it can take one to the knowledge that Confucius intended to transmit.

The third source is a long biography of Confucius written in the 1st century BCE. The author, Sima Qian, is China’s most distinguished historian, and the biography remains the standard in Chinese historiography. Even though later scholars did not find all his stories believable and saw logistical problems in his account of Confucius’s travels, they were willing to overlook such questions because of Sima Qian’s rare talent for improving the records imaginatively and reconstructing the interior lives of his subjects. In his biography of Confucius, Sima Qian tried to work mostly with the Analects, grouping individual utterances together to make them cohere and expanding isolated episodes by adding more characters and action. The biography was not altogether elegant or persuasive, but it was the earliest attempt to thread together into a continuous narrative the fragments in the Analects and the stories about Confucius that had been circulating through the works of historians and philosophers in the 300 years since his death.

Teachings of Confucius

Confucius thought that the rites, or ritual (li)—encompassing and expressing proper human conduct in all spheres of life—could steady a man and anchor a government and that their practice should begin at home. “Give your parents no cause for worry other than your illness,” he said. “When your parents are alive, do not travel to distant places, and if you have to travel, you must tell them exactly where you are going” (Analects, 2:6, 4:19). But what if your parents are thinking of doing something wrong? “Be gentle when trying to dissuade them from wrongdoing,” Confucius advised. “If you see that they are inclined not to heed your advice, remain reverent (jing). Do not openly challenge them. Do not be resentful even when they wear you out and make you anxious” (Analects, 4:18). Every human relationship is a balancing act, and the one between child and parents is the most demanding yet the most deserving of attention and patience, because it is rooted in love and the child’s earliest memories of warmth and affection. Confucius did not want children to be acquiescent in situations that call for their judgment. At the same time, he discouraged confrontation even when the parents are culpable. He worried that parents might lose their sense of proportion and their child’s affection for them, and so he urged the child to “remain reverent” even if the parents are not inclined to heed the child’s advice. The rites, therefore, enable the child to avoid a clash without having to betray principles. But unless the child “acts according to the spirit of the rites, in being respectful, he will tire himself out; in being cautious, he will become timid” (Analects, 8:2).

In the eyes of his contemporaries, Confucius was someone who embodied that spirit. They observed that “at court when he was speaking with the counselors of the lower rank, he was relaxed and affable. When speaking with counselors of the higher rank, he was frank but respectful. And in the ruler’s presence, though he was filled with reverence and awe, he was perfectly composed” (Analects,10:2).

The spirit of the rites is the ineffable, and, therefore, different from prescribed rules. It awaits the person with knowledge and awareness and skills in deportment to put it into motion, for every occasion is different. The circumstances change, and they change even as the occasion unfolds. Thus, when Confucius was inside the temple of the Duke of Zhou, “he asked questions about everything”; he knew the procedures of the sacrifice, yet he still approached the rites as if he were performing them for the first time. “Asking questions,” he said, “is the correct practice of the rites” (Analects, 3:15).

An education in the Odes, the earliest collection of Chinese poetry, complements an education in the rites. The Odes “can give the spirit exhortation, the mind keener eyes,” Confucius said. “They can make us better adjusted in a group and more articulate when voicing a complaint” (Analects, 17:9). He told his son, “Unless you learn the Odes, you won’t be able to speak” (Analects, 16:13). Just as the legendary sage emperor Shun (c. 23rd century BCE) told the director of music to teach the children poetry—to let the poems become their voice—so that “the straightforward shall yet be gentle, the magnanimous shall yet be dignified”—Confucius, too, hoped that the Odes would become his son’s speech, because such utterances are always appropriate and so will “never swerve from the path” (Analects, 2:2). For him, a love poem from the Odes, called Guanju (“Fishhawk”), best illustrates this point. The poem tells the reader that in yearning for the woman he desired, the wooer did not suffer unduly, and in courting his lady, he did not make a vulgar display of his feelings. The poem reads: “With harps we bring her company,” and “with bells and drums do her delight.” Of the tone and sentiment in this poem, Confucius said, “There is joy but no immodest thoughts, sorrow but no self-injury” (Analects, 3:20).

The music Confucius loved best was the ancient music known as shao. When he first heard it, he said, “I never imagined that music could be this beautiful,” and “for the next three months he did not notice the taste of meat” (Analects, 7:14). The music of shao is associated with the story of how Shun ascended to power upon the decision of Emperor Yao (c. 24th century BCE), Shun’s predecessor, to abdicate in favour of a man who grew up in the wilds but whose love for virtue was like the rush of a torrent. According to the Shujing, a compilation of documents related to China’s early history, when the music was played in the court of Emperor Shun, not only men but gods and spirits, birds and beasts were drawn to it. Such was the power of music that embodied the tenor and vehicle of a moral government.

Whereas Confucius looked upon music as the culmination of culture—of notes “bright and distinct” gathering in fluency and harmony—the Confucian philosopher Mencius (c. 371–c. 289 BCE) took the idea in another direction, seeing it as a trope of Confucius’s achievements (Analects, 3:23). In the work most closely associated with him (the Mencius), Mencius said that only Confucius could advance or retreat, serve or not serve “according to circumstances” and in a timely fashion, and, like a symphony perfectly brought together, “from the ringing of bells at the beginning to the sound of the jade tubes at the end,” there was an internal order (Mencius, 5B:1). The order found in the music of shao or in the conduct of a person suggests the ultimate good, but it is not an abstract idea, for it effects an emotional pull—a gravitating toward the music or the person possessing it. It has a kind of magic because it reflects a rightness in sound or in human deliberation. And this rightness of expression or intent serves a higher ideal, which Confucius called humaneness (ren).

When his disciple Zigong asked him what is humaneness, Confucius replied, “Do not impose on others what you do not want [others to impose on you]” (Analects, 15:24). A humane man is someone who is able “to make analogies from what is close at hand” (Analects, 6:30). He uses this knowledge to imagine the humanity in others, and he relies on his learning of rites and music to hold him to the right measure. Confucius was often asked whether someone was humane, and in response he always gave a careful assessment of the person’s strengths. He would say, for example, that the man “did his best” in fulfilling his public duty, “had administrative talents,” or “wanted nothing to defile him”—but such virtue, he would add, did not imply that the man was humane (Analects, 5:8; 5:19). In fact, Confucius claimed that he had never met anyone who was truly humane. This, however, did not mean that humaneness was beyond reach. “As soon as I desire humaneness, it is here,” he said, and everyone he had come across had sufficient strength “to devote all his effort to the practice of humaneness” (Analects, 7:30; 4:6). Humaneness “is beautiful (mei),” and most people are drawn to it, yet, Confucius observed, few will choose to pursue it (Analects, 4:1; 4:6). That resistance suggests a rich and more complex notion of human nature, without which morality could not come into play. And, as his disciple Zengzi (505–436 BCE) said, only the strong and resolute are game for the quest, because “the road is long” and “ends only with death.” (Analects, 8:7).

Confucius gave his teachings on humaneness a political dimension, though they seemed to be intended for the self. He observed that Emperor Shun was able to order the world simply by perfecting his own humanity and by cultivating a respectful demeanour. “If you set an example by correcting your mistakes, who dares not to correct his mistakes?” he asked the counselor Jikangzi. “Just desire the good and the people will be good. The character of those at the top is like that of the wind. The character of those below is like that of grass. When wind blows over the grass, the grass is sure to bend” (Analects, 12:17; 12:19). But when asked what should come first when administrating a state, he said “trust” (xin). If a ruler’s words and actions do not inspire trust, Confucius asserts, his government will certainly perish, even though he might ensure enough food to feed the people and adequate arms to defend them (Analects, 12:7). Confucius thought that the classic enfeoffment system of the early Zhou dynasty came very close to an ideal government because it was grounded in the trust between the Zhou emperor in the west and the relatives he sent east with vested authority to create new colonies for the young empire. Such a government, reinforced with the civilizing powers of rites and music, does not need complex laws and edicts to keep the people in check. Confucius said, “Guide the people with ordinances and statutes and keep them in line with [threats of] punishment, they will try to stay out of trouble but will have no sense of shame. If you guide them with exemplary virtue and keep them in line with the practice of the rites, they will have sense of shame and will know to reform themselves” (Analects, 2:3).

Few people knew how to reform themselves in Confucius’s time, and there was nearly no one among their rulers for them to look up to. But Confucius still had faith in professional advisers like himself, who, in the tradition of the great counselors of the past, were able to make rulers great with their hard work, discernment, and deft ways of moral suasion.

Later development of Confucian doctrines

The next 250 years of Chinese history, known as the Warring States Period, was even more fraught with tension and uncertainty than the one Confucius had known. A ruler’s success at this later time was measured by the size and number of his conquests, achieved through military operations and political maneuvers. The means to power also became more violent and sophisticated. Accordingly, followers of Confucius either held on to certain aspects of his teachings with a tighter grip or realized the need to adapt what he had said to the political reality of their times. Mencius was a member of the first group and Xunzi (c. 300–c. 230 BCE) of the second. Xunzi, who followed Mencius by about a century, severely criticized his predecessor. In his major work, now called the Xunzi, he accused Mencius of misleading “the dim-witted scholars of the vulgar age,” letting them believe that Mencius’s own “aberrant” and “esoteric” doctrines are the “true words” of Confucius (Xunzi, Chapter 6, “Contra Twelve Philosophers”). Later Confucians, who made much of the differences between the two philosophers, pointed to their theories of human nature as the source of their disagreement. But the fixation on that subject tended to obscure their more important differences regarding such topics as education and self-knowledge, feelings and intellect, law and adjudication, and the moral risks of a political profession.

Both Mencius and Xunzi took up the subject of moral judgment—the most difficult of human responsibilities in Confucius’s view—and explored it with greater precision and urgency than Confucius had done. On the question of which of the human faculties should play the deciding role, Mencius opted for the heart while Xunzi favoured the mind. Mencius believed that “every person has a heart that is sensitive to the sufferings of others”; therefore, he said, the sight of a young child about to fall into a well would horrify anyone who might be a witness and afflict that person with pain (Mencius, 2A:6). The horror—and the pain—is an unthinking response from the heart, which Mencius presented as proof that all humans are born with good impulses. People who lack the feeling of commiseration have only themselves to blame; they must have let go of their inborn nature, Mencius observed, and left their hearts morally barren (Mencius, 6A:8).

Mencius’s theory of human nature is bold. He claimed that he had gotten it from Confucius, though one learns from the Analects that Confucius did not like to talk about human nature (Analects, 5:13). However, given what Confucius said about learning—“Being human and yet lacking in humaneness—what can such a man do with the rites?” or “with music?”—he must have had some notion of human nature, which was likely to have been positive (Analects, 3:3). Mencius, for his part, wanted to go much further by using his theory of human nature as the basis of an entire moral philosophy. Thus, he speculated on ways of extending the heart’s potential and on how the larger world would be affected if that potential were fulfilled. Using a legendary figure to illustrate the key points of his teaching, Mencius related how the emperor Shun was able to emerge from the darkest of family histories (insensate father, cruel stepmother, and scheming half brother) to become a perfected self. Indeed, according to Mencius, at no time—not even when his family was plotting against his life—was Shun ever resentful or disrespectful toward his parents (Mencius, 5A:1, 2, 3). It was a moving, but not altogether credible, tale of strength gained through self-examination.

Confucius would have recognized Mencius’s story as an expression of what he had taught about filiality, but he would not have gone as far as Mencius did in making Shun the supreme model of filiality and in suggesting that such virtue was all a ruler would need “to give ease to his people” (Mencius, 5A.5). In fact, Confucius said that even Shun, a supremely cultivated ruler, found such a task “difficult to do” (Analects, 6.30).

Although Mencius’s political thought might today seem somewhat simplistic, he had a respectable following among the young; he also made a good living as a political counselor, and his service was often in demand. The rulers of his time did not mind listening to his remonstrances because, despite his reproving voice, he always included a positive message about their moral potential. He would tell them that no matter what sorts of transgressions they may have committed in the past, they could always recover their potential to do good if they applied themselves. Mencius was optimistic about the human condition and was willing to forego history and gloss over inconsistencies in his teachings in order to pursue his vision (Mencius, 7B:3).

Xunzi, on the other hand, was always seeking clarity—clarity of thought and words and a clear-eyed view of reality. He did not set out to challenge Mencius and did not mean to be polemical when he said that human nature is repellent. He simply wanted to give a discomforting and more truthful account of what human beings are like in order to get them moving more quickly on the road to reform. To that end, he wrote about desires—how to manage them before they become obsessively out of control (Xunzi, Chapter 21, “Dispelling Obsessions”); about power—how to use it effectively and properly when one has it; and about the difference between brute force and the authority of a true king (Xunzi, Chapter 11, “Kings and Lord-Protectors”). Xunzi traveled widely abroad and was active in political circles, working with several heads of state and witnessing their horrific deeds and misconduct. In fact, the most violent chapter in the history of the late Warring States Period occurred in Xunzi’s ancestral state of Zhao in the year 260 BCE, when Xunzi happened to be there. Thousands of Zhao soldiers were buried alive on this occasion by the army of the Qin dynasty after they had surrendered. Perhaps because of what he had seen and experienced, Xunzi liked to use startling images and shocking analogies in his writing to shake the men of his time from their mental lassitude and moral idleness. To one such man, a prime minister of the state of Qi who aspired to follow the great kings of the past but had not yet taken the first step, Xunzi said, “For you [to harbour such ambitions] is analogous to lying down flat on one’s face and trying to lick the sky or trying to rescue a man who had hanged himself by pulling at his feet” (Xunzi, Chapter 16, “On Strengthening the State”).

Along with his warnings, Xunzi offered guidance and examples from more distant history, using the Duke of Zhou and his father, Wenwang, among others, as models of conduct and character. Of the Duke of Zhou, Xunzi said that he was born into power and knew how to utilize it, and, even when his actions might have seemed irregular, people trusted him as they trusted the four seasons—such was the integrity of this man (Xunzi, Chapter 8: “Teachings of the Ru”).

Confucius also admired the Duke of Zhou for his political vision and for having seen the young dynasty through a perilous time. And he believed that having the trust of the people was the first item of business for a ruler, because without it the government could not stand on firm ground. In these ways, Confucius was Xunzi’s precursor. Confucius also stressed the importance of maintaining some emotional distance from matters that require judgment, but Xunzi placed more emphasis on the mind’s potential. He went as far as to say that a balanced and discerning mind could offer a more precise measure of right and wrong and that the perspicuity of the mind, not the stirring of the heart, should be a person’s moral compass. This was the essential difference between Xunzi and Mencius.

Many later Confucians sided with Mencius, and rulers tended to accept his teachings, as they did during Mencius’s lifetime, because his voice was less taxing on their conscience (rulers also knew that they could bend his words to suit their ways). Mencian ideas were spread further in the 11th and 12th centuries CE by Confucians of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Thinkers such as Cheng Yi (1033–1107) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200), in their attempt to create a new Confucian philosophy to meet the challenges of Buddhist metaphysics and meditative practices, finding preliminary support in Mencius’s concepts of human nature and self-cultivation, subscribed to Mencius’s understanding of Confucius. The Mencius also gained prominence in their academies. Successors of Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi in the subsequent Yuan dynasty (1206–1368) would go further by including the Mencius in government examinations, thus making his relationship with the state even tighter.

Xunzi, in the meantime, was pushed aside. Confucians in the Song and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties rejected him because his writings on human nature threatened to undermine their belief that the achievement of self-knowledge is the fulfillment of humanity’s inborn promise. Although there was more interest in Xunzi in the subsequent Qing dynasty (1644–1911/12), when scholars thought highly of his intellectual range and his writings on learning and politics, Xunzi did not supplant Mencius in the order of their affections. However, since the recent discovery of bamboo-strip texts dating from the Warring States Period (see below Contemporary scholarship on Confucian thought), Xunzi has gained more attention from scholars. Indeed, several of these excavated texts seem to resonate with Xunzi’s writings in both style and substance. That this should be so suggests that Confucius probably had a larger variety of heirs in early China than scholars have imagined, many more than the Song Confucians would have liked to believe. Confucius himself would have been pleased with this revelation. He would have preferred a richer and messier history of his legacy over any single line of transmission.

Contemporary scholarship on Confucian thought

In 1993, after the discovery of the bamboo-strip Analects, two other groups of manuscripts, on moral cultivation and political thought, were discovered in Hebei province, which led to a revival of scholarship on Confucian thought. The manuscripts, also written on bamboo strips, were dated to c. 300 BCE or earlier, during the Warring States Period, before China was unified. One batch of texts was dug up by archaeologists, and the other was taken by robbers from an unknown grave, smuggled to Hong Kong, and then sold to the Shanghai Museum through an arrangement orchestrated by antique dealers.

Confucius appeared, often with an interlocutor, in eight of the published texts from the Shanghai Museum collection. Since most of the texts are incomplete—with missing or damaged strips—it is difficult to establish just how much they add to scholars’ knowledge and idea of Confucius. Even so, the material evidence firmly places him in Warring States history. Either in conversation with a disciple or with a counselor about the drought in Lu or the cause of social unrest, this was a Confucius animated by speech and still trying to think through the most confounding problems of the human condition.

Early materials associated with Confucius continued to surface in the early 21st century. In 2011, an excavation of a Han dynasty tomb in the northern outskirts of the city of Nanchang, in Jiangxi province, uncovered a bamboo text of the Analects, a covered mirror with painted images of Confucius and two of his disciples, all identified by their names and short citations from the Analects, and Sima Qian’s biography of Confucius. The tomb belonged to Liu He, a grandson of the Han ruler Wudi. Liu He was made an emperor in 74 BCE at the age of 18 but was dethroned within 27 days—a victim of the political struggle going on at the time—and sent back to his ancestral home as a commoner. The ruler who succeeded him rehabilitated Liu He, granting him a title, Marquis Haihun, and a large fief just a few years before Liu He’s death in 59 BCE at the age of 33. Many piles of pottery and precious stones, gold cakes and gold utensils, and bronze instruments and jade ornaments accompanied Marquis Haihun to his grave, but so also did the image and words of Confucius, which suggests that even in death this young nobleman chose to stay close to what had become his moral compass in life.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Confucius (孔子; pinyin: Kǒngzǐ; lit. 'Master Kong'; c. 551 – c. 479 BCE), born Kong Qiu (孔丘), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the philosophy and teachings of Confucius.[1] His philosophical teachings, called Confucianism, emphasized personal and governmental morality, harmonious social relationships, righteousness, kindness, sincerity, and a ruler's responsibilities to lead by virtue.[2]

Confucius considered himself a transmitter for the values of earlier periods which he claimed had been abandoned in his time. He advocated for filial piety, endorsing strong family loyalty, ancestor veneration, the respect of elders by their children and of husbands by their wives. Confucius recommended a robust family unit as the cornerstone for an ideal government. He championed the Silver Rule, or a negative form of the Golden Rule, advising, "Do not do unto others what you do not want done to yourself."[3]

The time of Confucius's life saw a rich diversity of thought, and was a formative period in China's intellectual history. His ideas gained in prominence during the Warring States period, but experienced setback immediately following the Qin conquest. Under Emperor Wu of Han, Confucius's ideas received official sanction, with affiliated works becoming mandatory readings for career paths leading to officialdom. During the Tang and Song dynasties, Confucianism developed into a system known in the West as Neo-Confucianism, and later as New Confucianism. From ancient dynasties to the modern era, Confucianism has integrated into the Chinese social fabric and way of life.[4]

Traditionally, Confucius is credited with having authored or edited many of the ancient texts including all of the Five Classics. However, modern scholars exercise caution in attributing specific assertions to Confucius himself, for at least some of the texts and philosophy associated with him were of a more ancient origin.[5] Aphorisms concerning his teachings were compiled in the Analects, but not until many years after his death.

Name

The name "Confucius" is a Latinized form of the Mandarin Chinese Kǒng Fūzǐ (孔夫子, "Master Kong"), and was coined in the late 16th century by early Jesuit missionaries to China.[6] Confucius's family name was Kong (孔, OC:*kʰˤoŋʔ) and his given name was Qiu (丘, OC:*[k]ʷʰə). His courtesy name, a capping (guan: 冠) given at his coming of age ceremony,[7] and by which he would have been known to all but his older family members, was Zhongni (仲尼, OC:*N-truŋ-s nr[əj]), the "Zhòng" indicating that he was the second son in his family.[6][8]

Life

Early life

It is thought that Confucius was born on 28 September 551 BCE,[9][10] in Zou (鄒, in modern Shandong).[10][11] The area was notionally controlled by the kings of Zhou but effectively independent under the local lords of Lu, who ruled from the nearby city of Qufu. His father Kong He (or Shuliang He) was an elderly commandant of the local Lu garrison.[12] His ancestry traced back through the dukes of Song to the Shang dynasty which had preceded the Zhou.[13][14][15][16] Traditional accounts of Confucius's life relate that Kong He's grandfather had migrated the family from Song to Lu.[17] Not all modern scholars accept Confucius's descent from Song nobility.[18]: 14–15

Kong He died when Confucius was three years old, and Confucius was raised by his mother Yan Zhengzai (顏徵在) in poverty.[19] His mother later died at less than 40 years of age.[19] At age 19, he married Lady Qiguan (亓官氏), and a year later the couple had their first child, their son Kong Li (孔鯉).[19] Qiguan and Confucius later had two daughters together, one of whom is thought to have died as a child and one was named Kong Jiao (孔姣).[20]

Confucius was educated at schools for commoners, where he studied and learned the Six Arts.[21]

Confucius was born into the class of shi (士), between the aristocracy and the common people. He is said to have worked in various government jobs during his early 20s, and as a bookkeeper and a caretaker of sheep and horses, using the proceeds to give his mother a proper burial.[19][22] When his mother died, Confucius (aged 23) is said to have mourned for three years, as was the tradition.[22]

Political career

In Confucius's time, the state of Lu was headed by a ruling ducal house. Under the duke were three aristocratic families, whose heads bore the title of viscount and held hereditary positions in the Lu bureaucracy. The Ji family held the position "Minister over the Masses", who was also the "Prime Minister"; the Meng family held the position "Minister of Works"; and the Shu family held the position "Minister of War". In the winter of 505 BCE, Yang Hu—a retainer of the Ji family—rose up in rebellion and seized power from the Ji family. However, by the summer of 501 BCE, the three hereditary families had succeeded in expelling Yang Hu from Lu. By then, Confucius had built up a considerable reputation through his teachings, while the families came to see the value of proper conduct and righteousness, so they could achieve loyalty to a legitimate government. Thus, that year (501 BCE), Confucius came to be appointed to the minor position of governor of a town. Eventually, he rose to the position of Minister of Crime.[23] The Xunzi says that once assuming the post, Confucius ordered the execution of Shaozheng Mao, another Lu state official and scholar whose lectures attracted the three thousand disciples several times except Yan Hui. Shaozheng Mao was accused of 'five crimes', each worth execution, including 'concealed evilness, stubborn abnormality, eloquent duplicity, erudition in bizarre facts and generosity to evildoers'.[24]

Confucius desired to return the authority of the state to the duke by dismantling the fortifications of the city—strongholds belonging to the three families. This way, he could establish a centralized government. However, Confucius relied solely on diplomacy as he had no military authority himself. In 500 BCE, Hou Fan—the governor of Hou—revolted against his lord of the Shu family. Although the Meng and Shu families unsuccessfully besieged Hou, a loyalist official rose up with the people of Hou and forced Hou Fan to flee to the state of Qi. The situation may have been in favor for Confucius as this likely made it possible for Confucius and his disciples to convince the aristocratic families to dismantle the fortifications of their cities. Eventually, after a year and a half, Confucius and his disciples succeeded in convincing the Shu family to raze the walls of Hou, the Ji family in razing the walls of Bi, and the Meng family in razing the walls of Cheng. First, the Shu family led an army towards their city Hou and tore down its walls in 498 BCE.[25]

Soon thereafter, Gongshan Furao, a retainer of the Ji family, revolted and took control of the forces at Bi. He immediately launched an attack and entered the capital Lu. Earlier, Gongshan had approached Confucius to join him, which Confucius considered as he wanted the opportunity to put his principles into practice but he gave up on the idea in the end. Confucius disapproved the use of a violent revolution by principle, even though the Ji family dominated the Lu state by force for generations and had exiled the previous duke. Creel states that, unlike the rebel Yang Hu before him, Gongshan may have sought to destroy the three hereditary families and restore the power of the duke. However, Dubs is of the view that Gongshan was encouraged by Viscount Ji Huan to invade the Lu capital in an attempt to avoid dismantling the Bi fortified walls. Whatever the situation may have been, Gongshan was considered an upright man who continued to defend the state of Lu, even after he was forced to flee.[26]

During the revolt by Gongshan, Zhong You had managed to keep the duke and the three viscounts together at the court. Zhong You was one of the disciples of Confucius and Confucius had arranged for him to be given the position of governor by the Ji family. When Confucius heard of the raid, he requested that Viscount Ji Huan allow the duke and his court to retreat to a stronghold on his palace grounds. Thereafter, the heads of the three families and the duke retreated to the Ji's palace complex and ascended the Wuzi Terrace. Confucius ordered two officers to lead an assault against the rebels. At least one of the two officers was a retainer of the Ji family, but they were unable to refuse the orders while in the presence of the duke, viscounts, and court. The rebels were pursued and defeated at Gu. Immediately after the revolt was defeated, the Ji family razed the Bi city walls to the ground.[27]

The attackers retreated after realizing that they would have to become rebels against the state and their lord. Through Confucius' actions, the Bi officials had inadvertently revolted against their own lord, thus forcing Viscount Ji Huan's hand in having to dismantle the walls of Bi—as it could have harbored such rebels—or confess to instigating the event by going against proper conduct and righteousness as an official. Dubs suggests that the incident brought to light Confucius' foresight, practical political ability, and insight into human character.[28]

When it was time to dismantle the city walls of the Meng family, the governor was reluctant to have his city walls torn down and convinced the head of the Meng family not to do so. The Zuo Zhuan recalls that the governor advised against razing the walls to the ground as he said that it made Cheng vulnerable to Qi, and cause the destruction of the Meng family. Even though Viscount Meng Yi gave his word not to interfere with an attempt, he went back on his earlier promise to dismantle the walls.[29]

Later in 498 BCE, Duke Ding of Lu personally went with an army to lay siege to Cheng in an attempt to raze its walls to the ground, but he did not succeed. Thus, Confucius could not achieve the idealistic reforms that he wanted including restoration of the legitimate rule of the duke. He had made powerful enemies within the state, especially with Viscount Ji Huan, due to his successes so far. According to accounts in the Zuo Zhuan and the Records of the Grand Historian, Confucius departed his homeland in 497 BCE after his support for the failed attempt of dismantling the fortified city walls of the powerful Ji, Meng, and Shu families.[30] He left the state of Lu without resigning, remaining in self-exile and unable to return as long as Viscount Ji Huan was alive.[31]

Exile

The Shiji stated that the neighboring Qi state was worried that Lu was becoming too powerful while Confucius was involved in the government of the Lu state.[32] According to this account, Qi decided to sabotage Lu's reforms by sending 100 good horses and 80 beautiful dancing girls to the duke of Lu.[32] The duke indulged himself in pleasure and did not attend to official duties for three days. Confucius was disappointed and resolved to leave Lu and seek better opportunities, yet to leave at once would expose the misbehavior of the duke and therefore bring public humiliation to the ruler Confucius was serving. Confucius therefore waited for the duke to make a lesser mistake. Soon after, the duke neglected to send to Confucius a portion of the sacrificial meat that was his due according to custom, and Confucius seized upon this pretext to leave both his post and the Lu state.

After Confucius's resignation, he travelled around the principality states of north-east and central China including Wey, Song, Zheng, Cao, Chu, Qi, Chen, and Cai (and a failed attempt to go to Jin). At the courts of these states, he expounded his political beliefs but did not see them implemented.[33]

Return home

According to the Zuozhuan, Confucius returned home to his native Lu when he was 68, after he was invited to do so by Ji Kangzi, the chief minister of Lu.[34] The Shiji depicts him spending his last years teaching 3000 pupils, with 72 or 77 accomplished disciples that mastered the Six Arts. Meanwhile, Confucius dedicated himself in transmitting the old wisdom by writing or editing the Five Classics. [35]

During his return, Confucius sometimes acted as an advisor to several government officials in Lu, including Ji Kangzi, on matters including governance and crime.[34]

Burdened by the loss of both his son and his favorite disciples, he died at the age of 71 or 72 from natural causes. Confucius was buried on the bank of the Sishui River, to the north of Qufu City in Shandong Province. Starting as a humble tomb, the cemetery of Confucius had been expanded by emperors since the Han Dynasty. To date, the Cemetery of Confucius (孔林) covers an area of 183 hectares with more than 100,000 graves of the Kong descendants, it is included in the World Heritage List for its cultural and architectural value.[36][37]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

In the Analects, Confucius presents himself as a "transmitter who invented nothing". He puts the greatest emphasis on the importance of study, and it is the Chinese character for study (學) that opens the text. Far from trying to build a systematic or formalist theory, he wanted his disciples to master and internalize older classics, so that they can capture the ancient wisdoms that promotes "harmony and order", to aid their self-cultivation to become a perfect man. For example, the Annals would allow them to relate the moral problems of the present to past political events; the Book of Odes reflects the "mood and concerns" of the commoners and their view on government; while the Book of Changes encompasses the key theory and practice of divination. [38] [39]

Although some Chinese people follow Confucianism in a religious manner, many argue that its values are secular and that it is less a religion than a secular morality. Proponents of religious Confucianism argue that despite the secular nature of Confucianism's teachings, it is based on a worldview that is religious.[40] Confucius was considered more of a humanist than a spiritualist,[41] his discussions on afterlife and views concerning Heaven remained indeterminate, and he is largely unconcerned with spiritual matters often considered essential to religious thought, such as the nature of souls.[42]

Ethics

One of the deepest teachings of Confucius may have been the superiority of personal exemplification over explicit rules of behavior. His moral teachings emphasized self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled judgment rather than knowledge of rules. Confucian ethics may, therefore, be considered a type of virtue ethics. His teachings rarely rely on reasoned argument, and ethical ideals and methods are conveyed indirectly, through allusion, innuendo, and even tautology. His teachings require examination and context to be understood. A good example is found in this famous anecdote:

This remark was considered a strong manifestation of Confucius' advocacy in humanism. [43] [44]

One of his teachings was a variant of the Golden Rule, sometimes called the "Silver Rule" owing to its negative form:

Often overlooked in Confucian ethics are the virtues to the self: sincerity and the cultivation of knowledge. Virtuous action towards others begins with virtuous and sincere thought, which begins with knowledge. A virtuous disposition without knowledge is susceptible to corruption, and virtuous action without sincerity is not true righteousness. Cultivating knowledge and sincerity is also important for one's own sake; the superior person loves learning for the sake of learning and righteousness for the sake of righteousness.[citation needed]

The Confucian theory of ethics as exemplified in lǐ (禮) is based on three important conceptual aspects of life: (a) ceremonies associated with sacrifice to ancestors and deities of various types, (b) social and political institutions, and (c) the etiquette of daily behavior. Some believed that lǐ originated from the heavens, but Confucius stressed the development of lǐ through the actions of sage leaders in human history. His discussions of lǐ seem to redefine the term to refer to all actions committed by a person to build the ideal society, rather than those conforming with canonical standards of ceremony.[45]

In the early Confucian tradition, lǐ was doing the proper thing at the proper time; balancing between maintaining existing norms to perpetuate an ethical social fabric, and violating them in order to accomplish ethical good. Training in the lǐ of past sages, cultivates virtues in people that include ethical judgment about when lǐ must be adapted in light of situational contexts.

In Confucianism, the concept of li is closely related to yì (義), which is based upon the idea of reciprocity. Yì can be translated as righteousness, though it may mean what is ethically best to do in a certain context. The term contrasts with action done out of self-interest. While pursuing one's own self-interest is not necessarily bad, one would be a better, more righteous person if one's life was based upon following a path designed to enhance the greater good. Thus an outcome of yì is doing the right thing for the right reason.[citation needed]

Just as action according to lǐ should be adapted to conform to the aspiration of adhering to yì, so yì is linked to the core value of rén (仁). Rén consists of five basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness.[46] Rén is the virtue of perfectly fulfilling one's responsibilities toward others, most often translated as "benevolence", "humaneness", or "empathy"; translator Arthur Waley calls it "Goodness" (with a capital G), and other translations that have been put forth include "authoritativeness" and "selflessness". Confucius's moral system was based upon empathy and understanding others, rather than divinely ordained rules. To develop one's spontaneous responses of rén so that these could guide action intuitively was even better than living by the rules of yì. Confucius asserts that virtue is a mean between extremes. For example, the properly generous person gives the right amount – not too much and not too little.[46]

Politics

Confucius's political thought is based upon his ethical thought. He argued that the best government is one that rules through "rites" (lǐ) and morality, and not by using incentives and coercion. He explained that this is one of the most important analects: "If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of the shame, and moreover will become good." (Analects 2.3, tr. Legge). This "sense of shame" is an internalization of duty. Confucianism prioritizes creating a harmonious society over the ruler's interests, opposes material incentives and harsh punishments, and downplays the role of institutions in guiding behavior as in Legalism, emphasizing moral virtues instead.[47]

Confucius looked nostalgically upon earlier days, and urged the Chinese, particularly those with political power, to model themselves on earlier examples. In times of division, chaos, and endless wars between feudal states, he wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven (天命) that could unify the "world" (天下, "all under Heaven") and bestow peace and prosperity on the people. Because his vision of personal and social perfections was framed as a revival of the ordered society of earlier times, Confucius is often considered a great proponent of conservatism, but a closer look at what he proposes often shows that he used (and perhaps twisted) past institutions and rites to push a new political agenda of his own: a revival of a unified royal state, whose rulers would succeed to power on the basis of their moral merits instead of lineage. These would be rulers devoted to their people, striving for personal and social perfection, and such a ruler would spread his own virtues to the people instead of imposing proper behavior with laws and rules.[48]

While Confucius supported the idea of government ruling by a virtuous king, his ideas contained a number of elements to limit the power of rulers. He argued for representing truth in language, and honesty was of paramount importance. Even in facial expression, truth must always be represented.[citation needed] Confucius believed that if a ruler is to lead correctly, by action, that orders would be unnecessary in that others will follow the proper actions of their ruler. In discussing the relationship between a king and his subject (or a father and his son), he underlined the need to give due respect to superiors. This demanded that the subordinates must advise their superiors if the superiors are considered to be taking a course of action that is wrong. Confucius believed in ruling by example, if you lead correctly, orders by force or punishment are not necessary.[49]

Music and poetry

Confucius heavily promoted the use of music with rituals or the rites order.[further explanation needed] The scholar Li Zehou argued that Confucianism is based on the idea of rites. Rites serve as the starting point for each individual and that these sacred social functions allow each person's human nature to be harmonious with reality. Given this, Confucius believed that "music is the harmonization of heaven and earth; the rites is the order of heaven and earth". Thus the application of music in rites creates the order that makes it possible for society to prosper.[50]

The Confucian approach to music was heavily inspired by the Classic of Poetry and the Classic of Music, which was said to be the sixth Confucian classic until it was lost during the Han dynasty. The Classic of Poetry serves as one of the current Confucian classics and is a book on poetry that contains a diversified variety of poems as well as folk songs. Confucius is traditionally ascribed with compiling these classics within his school.[51] In the Analects, Confucius described the importance of the poetry in the intellectual and moral development of an individual:[52][53]

Confucius frowned upon globalization encroaching on China, especially with music, and he preached against musical influences from Persians, Greco-Bactrians, and Mongols.[54]

Legacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

Confucius's teachings were later turned into an elaborate set of rules and practices by his numerous disciples and followers, who organized his teachings into the Analects.[55][56] Confucius's disciples and his only grandson, Zisi, continued his philosophical school after his death.[57] These efforts spread Confucian ideals to students who then became officials in many of the royal courts in China, thereby giving Confucianism the first wide-scale test of its dogma.[58]

Two of Confucius's most famous later followers emphasized radically different aspects of his teachings. In the centuries after his death, Mencius (孟子) and Xunzi (荀子) both composed important teachings elaborating in different ways on the fundamental ideas associated with Confucius. Mencius (4th century BCE) articulated the innate goodness in human beings as a source of the ethical intuitions that guide people towards rén, yì, and lǐ, while Xunzi (3rd century BCE) underscored the realistic and materialistic aspects of Confucian thought, stressing that morality was inculcated in society through tradition and in individuals through training. In time, their writings, together with the Analects and other core texts came to constitute the philosophical corpus of Confucianism.[59][better source needed]

This realignment in Confucian thought was parallel to the development of Legalism, which held that humanity and righteousness were not sufficient in government, and that rulers should instead rely on statecrafts, punishments, and law. [60] A disagreement between these two political philosophies came to a head in 223 BCE when the Qin state conquered all of China. Li Si, Prime Minister of the Qin dynasty, convinced Qin Shi Huang to abandon the Confucians' recommendation of awarding fiefs akin to the Zhou dynasty before them which he saw as being against to the Legalist idea of centralizing the state around the ruler.[citation needed] [anachronism]

Under the succeeding Han and Tang dynasties, Confucian ideas gained even more widespread prominence. Under Emperor Wu of Han, the works attributed to Confucius were made the official imperial philosophy and required reading for civil service examinations in 140 BCE which was continued nearly unbroken until the end of the 19th century. As Mohism lost support by the time of the Han, the main philosophical contenders were Legalism, which Confucian thought somewhat absorbed, the teachings of Laozi, whose focus on more spiritual ideas kept it from direct conflict with Confucianism, and the new Buddhist religion, which gained acceptance during the Southern and Northern Dynasties era. Both Confucian ideas and Confucian-trained officials were relied upon in the Ming dynasty and even the Yuan dynasty, although Kublai Khan distrusted handing over provincial control to them.[citation needed]

During the Song dynasty, Confucianism was revitalized in a movement known as Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism was a revival of Confucianism that expanded on classical theories by incorporating metaphysics and new approaches to self-cultivation and enlightenment, influenced by Buddhism and Daoism. [61] The most renowned scholar of this period was Zhu Xi (1130-1200CE). There are clear Buddhist and Daoist influences in the Neo-Confucian advocacy of "quiet sitting" (meditation) as a technique of self-cultivation that leads to transformative experiences of insight." [62] In his life, Zhu Xi was largely ignored, but not long after his death, his ideas became the new orthodox view of what Confucian texts actually meant.[63] Modern historians view Zhu Xi as having created something rather different and call his way of thinking Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism held sway in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam until the 19th century. [64]

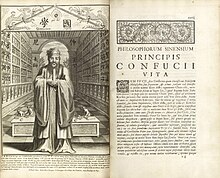

The works of Confucius were first translated into European languages by Jesuit missionaries in the 16th century during the late Ming dynasty. The first known effort was by Michele Ruggieri, who returned to Italy in 1588 and carried on his translations while residing in Salerno. Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and a team of Jesuits—Prospero Intorcetta, Philippe Couplet, and two others—published a translation of several Confucian works and an overview of Chinese history in Paris in 1687.[65][66] François Noël, after failing to persuade Clement XI that Chinese veneration of ancestors and Confucius did not constitute idolatry, completed the Confucian canon at Prague in 1711, with more scholarly treatments of the other works and the first translation of the collected works of Mencius.[67] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilization.[66][68]

In the modern era Confucian movements, such as New Confucianism, still exist, but during the Cultural Revolution, Confucianism was frequently attacked by leading figures in the Chinese Communist Party. This was partially a continuation of the condemnations of Confucianism by intellectuals and activists in the early 20th century as a cause of the ethnocentric close-mindedness and refusal of the Qing dynasty to modernize that led to the tragedies that befell China in the 19th century. [69]

Confucius's works are studied by scholars in many other Asian countries, particularly those in the Chinese cultural sphere, such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Many of those countries still hold the traditional memorial ceremony every year.[citation needed]

Among Tibetans, Confucius is often worshipped as a holy king and master of magic, divination and astrology. Tibetan Buddhists see him as learning divination from the Buddha Manjushri (and that knowledge subsequently reaching Tibet through Princess Wencheng), while Bon practitioners see him as being a reincarnation of Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, the legendary founder of Bon.[70]

The Ahmadiyya believes Confucius was a Divine Prophet of God, as were Lao-Tzu and other eminent Chinese personages.[71]

According to the Siddhar tradition of Tamil Nadu, Confucius is one of the 18 esteemed Siddhars of yore, and is better known as Kalangi Nathar or Kamalamuni.[72][73][74] The Thyagaraja Temple in Thiruvarur, Tamil Nadu is home to his Jeeva Samadhi.[75]

In modern times, Asteroid 7853, "Confucius", was named after the Chinese thinker.[76]

Teaching and Disciples

Confucius was regarded as the first teacher who advocated for public welfare and the spread of education in China.[77][78] Confucius devoted his entire life, from a relatively young age, to teaching. He pioneered private education adopting a curriculum known as the Six Arts, aimed at making education accessible to all social classes, and believed in its power to cultivate character rather than merely vocational skills. Confucius not only made teaching his profession but also contributed to the development of a distinct class of professionals in ancient China—the gentlemen who were neither farmers, artisans, merchants, nor officials but instead dedicated themselves to teaching and potential government service.[35][79]

Confucius began teaching after he turned 30, and taught more than 3,000 students in his life, about 70 of whom were considered outstanding. His disciples and the early Confucian community they formed became the most influential intellectual force in the Warring States period.[80] The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian dedicated a chapter in his Records of the Grand Historian to the biographies of Confucius's disciples, accounting for the influence they exerted in their time and afterward. Sima Qian recorded the names of 77 disciples in his collective biography, while Kongzi Jiayu, another early source, records 76, not completely overlapping. The two sources together yield the names of 96 disciples.[81] Twenty-two of them are mentioned in the Analects, while the Mencius records 24.[82]

Confucius did not charge any tuition, and only requested a symbolic gift of a bundle of dried meat from any prospective student. According to his disciple Zigong, his master treated students like doctors treated patients and did not turn anybody away.[81] Most of them came from Lu, Confucius's home state, with 43 recorded, but he accepted students from all over China, with six from the state of Wey (such as Zigong), three from Qin, two each from Chen and Qi, and one each from Cai, Chu, and Song.[81] Confucius considered his students' personal background irrelevant, and accepted noblemen, commoners, and even former criminals such as Yan Zhuoju and Gongye Chang.[83] His disciples from richer families would pay a sum commensurate with their wealth which was considered a ritual donation.[81]

Confucius's favorite disciple was Yan Hui, most probably one of the most impoverished of them all.[82] Sima Niu, in contrast to Yan Hui, was from a hereditary noble family hailing from the Song state.[82] Under Confucius's teachings, the disciples became well learned in the principles and methods of government.[84] He often engaged in discussion and debate with his students and gave high importance to their studies in history, poetry, and ritual.[84] Confucius advocated loyalty to principle rather than to individual acumen, in which reform was to be achieved by persuasion rather than violence.[84] Even though Confucius denounced them for their practices, the aristocracy was likely attracted to the idea of having trustworthy officials who were studied in morals as the circumstances of the time made it desirable.[84] In fact, the disciple Zilu even died defending his ruler in Wey.[84]