88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

February 15, 2021

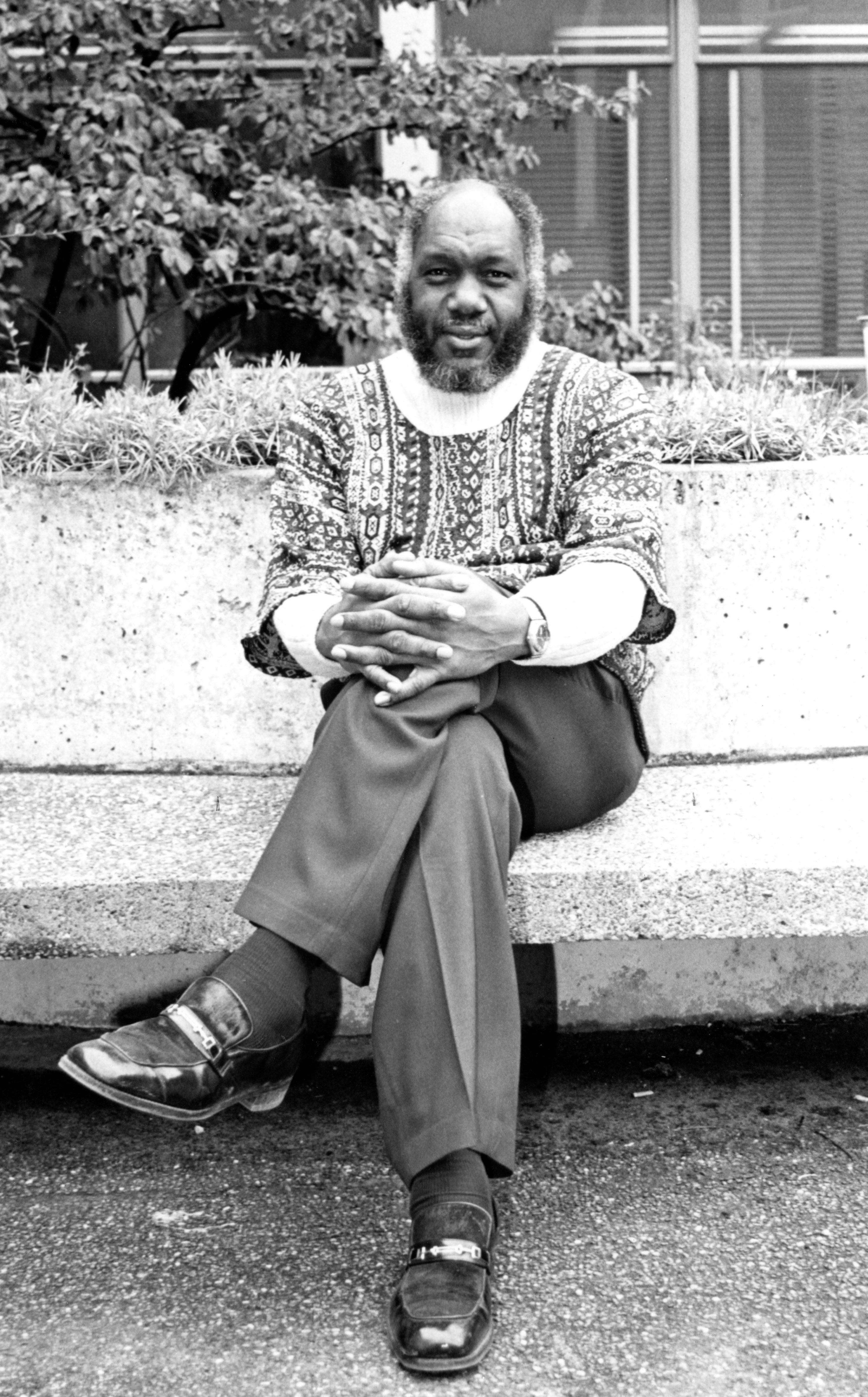

He didn’t set out to change how business was taught at public universities, but Thaddeus Spratlen (BSBA ’56, MA ’57, PhD ’62) transformed the way business schools deliver business education, and after nearly six decades, his pioneering work continues to influence generations of scholars, their students and underrepresented communities.

To understand Thaddeus Spratlen, now 90 years old, it’s imperative to understand where he came from.

Born in Union City, Tennessee in 1930, he grew up in the south during the Great Depression where, resources were scarce; yet his father, a Baptist minister preached the pursuit of excellence. It wasn’t just that the Spratlen family thrived in the face of these challenges, it was that they were expected to.

“There was an expectation of excellence in his house. Excellence in yourself and excellence in who, and what you chose to surround yourself with,” says Townsand Price-Spratlen, associate professor of sociology at Ohio State, and Thaddeus’ second son.

During a time when speaking of the “north” and the “south” denoted racial connotations, Thaddeus was sent “north” to family in Cleveland for access to better educational opportunities. He graduated from what was then Central High School before enrolling at Kent State University.

Economic constraints of the 1940s and the passing of his father forced him to abandon his academic pursuits — first to help contribute to the family finances and then to join the military, where he served in the Korean War. Through the G.I. Bill, however, Thaddeus resumed his education at Ohio State, eventually earning three degrees and becoming a triple Buckeye.

His dad’s greatest treasure, says Townsand, was meeting and marrying his wife, Lois Price. They were introduced by mutual friends at a military ball. Soon they were husband and wife, and best friends for over 60 years.

Lois was a hospital psychiatric nurse who earned her PhD, not in nursing, but in urban planning where she could tackle community issues of equity in public health. She later became a university ombudsman emeritus at the University of Washington. Together, Thaddeus and Lois, who passed away from cancer in 2013, became a formidable team everywhere they lived and worked during their marriage.

They raised five children — a second generation of excellence: Pamela L. Spratlen held two ambassadorships for the U.S. in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan; two-time Olympian Pat Spratlen Etem is a public health community organizer and a mother of three; Paula Spratlen Mitchell, is a high school teacher, tennis and volleyball coach and a mother of two; and Khalfani Mwamba, is a clinical social worker, lecturer at UW School of Social Work and a father of four.

Teaching in the 1960s

In the 1960s, the cultural expectation of someone like Thaddeus, a Black PhD, was a career teaching in the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) system.

After defending his PhD at Ohio State in 1962, Thaddeus and a colleague decided against this particular expectation.

“At that time, it was most common, no matter where you got your PhD, whether it was Harvard or Princeton — it didn’t matter — the pattern of segregation, hiring in the academic marketplace was almost totally segregated,” Thaddeus recalls in an interview with the University of Washington, where he spent the majority of his teaching career.

It was also a time when faculty could be hired without a visit, a decision based solely on their resume or CV, which often contained a printed photo of themselves.

Thaddeus was one of three finalists for a position at what was then Western Washington State College (now Western Washington University). Before presenting the resumes to the faculty, Thaddeus said, the head of the search committee removed all three men’s photos.

Thaddeus was offered the job based on his background and qualifications.

“Until the late 1960s, there were no African-American faculty. So that was a huge, major change in hiring, in the culture, in the way in which individuals of color were received and perceived in the 1960s,” he recounts in the interview. “This was part of the civil rights movement, a part of affirmative action that major universities like UW, UCLA and so on actually themselves, began to desegregate the faculty.”

Over the course of the next five decades, he taught at Western, UCLA and then the University of Washington, where his work continues to impact the university and the small college community of Bellingham, Washington.

Distinguishable Firsts

Thaddeus settled into his UW faculty role in 1972, advancing coursework, organizing and participating in social justice causes, building relationships and establishing his research agenda.

He was the first Black faculty member at the University of Washington Michael G. Foster School of Business. In the ensuing years, he would achieve many “firsts” at Foster, including the first Black faculty member to earn tenure, and the first to earn the designation of professor emeritus.

Thaddeus was among the first to embrace the belief that students could learn by working with real businesses, and that businesses could learn from students. No one benefitted when “ivory tower know-it-alls” dropped into a business and cited academic theory then left the business to find ways to incorporate the ideas. Beyond the classroom, he engaged his business students in doing work off-campus with local, Black-owned businesses where they could put theory into practice.

By the mid-1990s, Thaddeus and his colleague, David Gautschi had formalized and started teaching an experimental class called “Urban Crisis and the Contemporary Marketing Challenge.” The class examined what was happening in Black America from a marketing perspective.

It was in this class that Thaddeus crossed paths with MBA student Michael Verchot.

“What we saw was that, for generations, geographic communities had been underinvested. So the question was, ‘why was that the case? It really centered around distortions of the marketplace and market failure,” says Michael, who now directs the Consulting and Business Development Center at Foster. “The class focused on an underinvested community, examined the market failures, and asked questions like, what do businesses do about these failures and why are businesses owned by Black, Latino and other people of color struggling to get loans and investments?”

Experiential Learning

With the success of the class, in 1995 Thaddeus and other UW academic leaders began to evaluate how the class could be made permanent, as well as steps the business school could take to create ongoing engagement with Black-owned businesses in the community. They knew they could enrich the students’ experience if outreach and problem solving in the community complemented their classroom learning.

Like entrepreneurs everywhere, they put together a business plan, figured out how to pay for the proposed program, and shared it with the new dean of the Foster, William Bradford (MBA ’68, PhD ’72), the first Black dean of the business school and a Buckeye.

The experimental class-turned-business plan eventually evolved into the school’s Consulting and Business Development Center. At the heart of the center were many of the strategies and tactics pioneered by Thaddeus decades earlier, namely accelerating student careers by applying classroom teaching to real-world business and helping to create jobs in underserved communities across Washington.

“Thad’s greatest contribution is normalizing and promoting the pedagogical approach that public business schools need to be engaged with the community,” says Michael. “The center is the embodiment of who Thad is. He’s been a professor emeritus for 18 years now, and to this day, I won’t make a major decision about this center without consulting him.”

For Townsand, his father’s legacy is one that demonstrates the power of academic thought leadership and its ability to bring about positive impact and change.

“Dad’s living mission, his life’s work boils down to economic inclusion and enhancing social justice and community well-being through economic stability,” says Townsand.

No comments:

Post a Comment