Hurricane Carter, Ferocious Boxer and Cause Célèbre

Associated Press

Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, a star prizefighter whose career was cut short by a murder conviction in New Jersey and who became an international cause célèbre while imprisoned for 19 years before the charges against him were dismissed, died on Sunday morning at his home in Toronto. He was 76.

The cause of death was prostate cancer, his friend and onetime co-defendant, John Artis, said. Mr. Carter was being treated in Toronto, where he had founded a nonprofit organization, Innocence International, to work to free prisoners it considered wrongly convicted.

Mr. Carter was convicted twice on the same charges of fatally shooting two men and a woman in a Paterson, N.J., tavern in 1966. But both jury verdicts were overturned on different grounds of prosecutorial misconduct.

The legal battles consumed scores of hearings involving recanted testimony, suppressed evidence, allegations of prosecutorial racial bias — Mr. Carter was black and the shooting victims were white — and a failed prosecution appeal to the United States Supreme Court to reinstate the convictions.

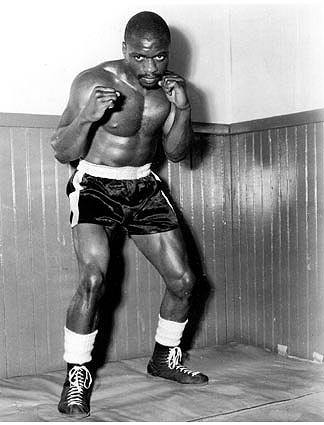

Mr. Carter first became famous as a ferocious, charismatic, crowd-pleasing boxer who was known for his shaved head, goatee, glowering visage and devastating left hook. He narrowly lost a fight for the middleweight championship in 1964.

He attracted worldwide attention during the roller-coaster campaign to clear his name of murder charges. Amnesty International described him as a “prisoner of conscience” whose human rights had been violated. He portrayed himself as a victim of injustice who had been framed because he spoke out for civil rights and against police brutality.

A defense committee studded with entertainment, sports, civil rights and political personalities was organized. His cause entered the realm of pop music when Bob Dylan wrote and recorded the song “Hurricane,” which championed his innocence and vilified the police and prosecution witnesses. It became a Top 40 hit in 1976.

Mr. Carter’s life was also the subject of a 1999 movie, “The Hurricane,” in which he was played by Denzel Washington, who was nominated for an Academy Award for the performance. The movie, directed by Norman Jewison, was widely criticized as simplistic and rife with historical inaccuracies.

A more complex picture was provided in accounts by Mr. Carter’s relatives and supporters, and by Mr. Carter himself in his autobiography, “The 16th Round,” published in 1974 while he was in prison. He attracted supporters even when his legal plight seemed hopeless, but he also alienated many of them, including his first wife.

With a formal education that ended in the eighth grade in a reform school, Mr. Carter survived imprisonment and frequent solitary confinement by becoming a voracious reader of law books and volumes of philosophy, history, metaphysics and religion. During his bleakest moments, he expressed confidence that he would one day be proved innocent.

“They can incarcerate my body but never my mind,” he told The New York Times in 1977, shortly after his second conviction.

Troubled From the Start

Rubin Carter was born on May 6, 1937, in Clifton, N.J., and grew up nearby in Passaic and Paterson. His father, Lloyd, and his mother, Bertha, had moved there from Georgia. To support his wife and seven children, Lloyd Carter worked in a rubber factory and operated an ice-delivery service in the mornings.

A deacon in the Baptist church, his father was also a disciplinarian. He put Rubin to work cutting and delivering ice at age 8, and when he learned that Rubin, at 9, and some other boys had stolen clothing from a Paterson store, he turned his son in to the police. Rubin was placed on two years’ probation.

A poor student and troubled from the start, Rubin was placed in a school for unruly pupils when he was in the fourth grade. At 11, after stabbing a man, he was sent to the Jamesburg State Home for Boys (now called the New Jersey Training School for Boys). He said he had acted in self-defense after the man had made sexual advances and tried to throw him off a cliff. At Jamesburg, guards frequently beat and abused him, he wrote in his autobiography.

After six years in detention he escaped and made his way to an aunt’s home in Philadelphia, where he enlisted in the Army. Recruitment officers apparently accepted his word that he had grown up in Philadelphia and made no inquiries in New Jersey, where he was wanted as a fugitive.

Thriving in the Army, Mr. Carter became a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division in Germany and put on boxing gloves for the first time. He found he enjoyed associating with boxers. “They were strong, honest people, hardworking and equally hard-fighting,” he recalled. “There were no complications there whatsoever, no tensions, no fears.”

He won 51 bouts, 35 by knockouts, while losing only five. He became the Army’s European light-welterweight champion.

Mr. Carter also took speech therapy courses and overcame his stutter. He became interested in Islamic studies. Although he never formally converted, he sometimes used the Muslim name Saladin Abdullah Muhammad. Honorably discharged, he returned to Paterson in 1956 and took a job as a tractor-trailer driver. But the authorities tracked him down and arrested him for his escape from the reform school before he had joined the Army. He was sentenced to 10 months at the Annandale Reformatory for youthful offenders.

Shortly after his release, in 1957, he was charged with snatching a woman’s purse and assaulting a man on a Paterson street. He said he had been drinking. He served four years in Trenton State Prison, where “quiet rage became my constant companion,” he wrote. He also rekindled his interest in boxing and attracted the attention of fight managers.

On Sept. 22, 1961, a day after his release from prison, he fought his first professional fight, winning a four-round decision for a $20 purse. “I was in my element now,” he wrote. “Fighting was the pulse beat of my heart and I loved it.”

Mr. Carter was an instant success and became a main-event headliner. With a powerful left hook, he was more of a puncher than a stylist, winning 13 of his first 21 fights by knockouts.

Showman in the Ring

Promoters capitalized on his criminal record as a box-office lure, suggesting that prison had transformed him into a terrifying fighter. One promoter nicknamed him Hurricane, describing him in advertisements as a raging, destructive force.

Mr. Carter was a showman in the ring. Solidly built at 5-foot-8 and about 155 pounds, he would enter in a hooded black velvet robe trimmed with metallic gold thread, the image of a crouching black panther on the back.

He also made sure he was noticed on the streets of Paterson, where he had returned to live. He dressed in custom-tailored suits and drove a black Cadillac Eldorado with “Rubin Hurricane Carter” engraved in silver letters on each side of the headlights. In 1963 he married Mae Thelma Basket.

Mr. Carter’s biggest victory came in Pittsburgh in December 1963, when he knocked out Emile Griffith, the welterweight champion, who was trying to move into the middleweight division for a crack at its world title. A year later, at the peak of his career, Mr. Carter battled the reigning middleweight champion, Joey Giardello, for the title in Philadelphia, Mr. Giardello’s hometown. He lost a close decision.

Mr. Carter received unfavorable attention when an article in The Saturday Evening Post in 1964 suggested that he was a black militant who believed that blacks should shoot at the police if they felt they were being victimized. He denied he had expressed that view. It was around this time that the police began harassing him, he said. One night, when his Cadillac broke down in Hackensack, he was jailed for several hours without being charged with a crime.

Before bouts, the police compelled him to be fingerprinted and photographed for their files on the ground that he was a convicted felon. He discovered that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had opened a file on him and was tracking his movements.

On the night of June 16 and the early morning of June 17, 1966, while his wife and their 2-year-old daughter, Theodora, were at home, Mr. Carter visited several bars in Paterson, winding up at one called the Night Spot.

A half-mile away, about 2:30 a.m., two black men entered the Lafayette Grill and killed two white men and a white woman in a barrage of shotgun and pistol blasts. The police immediately suspected that the shootings were in retaliation for the shotgun murder that night in Paterson of a black tavern owner by the former owner, who was white.

Mr. Carter had encountered John Artis, a casual acquaintance, that night and was giving him a lift home when they were stopped by the police. They said Mr. Carter’s leased white Dodge sedan resembled the murderers’ getaway car. Except for being black, neither Mr. Carter nor Mr. Artis matched the original descriptions of the killers. They were released after both passed lie detector tests and a patron who had been wounded in the Lafayette Grill failed to identify them. But they remained under suspicion.

On Aug. 6, 1966, in Rosario, Argentina, Mr. Carter lost a 10-round decision to Rocky Rivero. It was his last fight. His record would remain 27 wins (20 by knockout), 12 losses and one draw. Two months later, he and Mr. Artis were charged with the three murders.

Burglars Testify

At their trial in 1967, three alibi witnesses placed them elsewhere at the time of the killings. They were nonetheless convicted, primarily on the evidence of Alfred P. Bello and Arthur D. Bradley, two white prosecution witnesses with long criminal records. Mr. Bello testified that he saw both defendants leave the tavern with guns in their hands; Mr. Bradley identified only Mr. Carter.

Both witnesses admitted that they were in the vicinity of the Lafayette Grill at the time of the murders because they were trying to burglarize a factory nearby.

The prosecution offered no motive for the slayings.

Facing the possibility of death sentences, Mr. Carter received 30 years to life and Mr. Artis 15 years to life. Their appeals were denied unanimously by the New Jersey Supreme Court.

Back in prison, a defiant Mr. Carter refused to wear a uniform or work at institutional jobs. He ate in his cell, sustained by canned food and soup that he heated with an electric coil. He scoured the trial record and law books and typed out unsuccessful briefs for a new trial.

Mr. Carter also lost his vision in his right eye after an operation on a detached retina, a condition he attributed to inadequate treatment in a prison hospital. His celebrity boxing background and his outspoken contempt for prison rules made him a hero to many inmates. The prison authorities credited him with trying to calm down rioters at Rahway State Prison in 1971, and one prison guard reportedly said Mr. Carter had saved his life.

Witnesses Recant

Advertisement

By 1974, Mr. Carter’s prospects for a new trial seemed hopeless. But that summer the New Jersey Public Defender’s Office and The New York Times independently obtained recantations from Mr. Bello and Mr. Bradley. Both men asserted that detectives had pressured them into falsely identifying Mr. Carter and Mr. Artis.

Moreover, it was revealed that the prosecution had secretly promised leniency to the two witnesses regarding their own crimes in exchange for their cooperation in the Carter case.

Based on the recantations and the new information, the New Jersey Supreme Court overturned the guilty verdicts in 1976. Overnight, Mr. Carter was hailed as a civil rights champion, with a national defense committee working on his behalf and fund-raising concerts headlined by Mr. Dylan at Madison Square Garden and the Houston Astrodome; the Garden concert also included Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez and Roberta Flack. Muhammad Ali attended a pretrial hearing in Paterson in 1976 to show his support for Mr. Carter.

At a second trial, in December 1976, a new team of Passaic County prosecutors resuscitated an old theory, charging that the defendants had committed the Lafayette Grill murders to exact revenge for the earlier killing of the black tavern owner. Mr. Bello resurfaced as a prosecution witness and recanted his recantation. He was the only witness who placed Mr. Carter and Mr. Artis at the murder scene.

After being free for nine months on bail, Mr. Carter and Mr. Artis were sent back to prison and deserted by most of the show business and civil rights figures who had flocked to their cause. Mr. Carter’s second child, a son, Raheem Rubin, was born six days after the two men were found guilty.

Racial Revenge Theory

Over the next nine years, numerous appeals in New Jersey courts failed. But when the issues were heard for the first time in a federal court, in 1985, Judge H. Lee Sarokin of United States District Court in Newark overturned the convictions on constitutional grounds. He ruled that prosecutors had “fatally infected the trial” by resorting, without evidence, to the racial revenge theory, and that they had withheld evidence disproving Mr. Bello’s identifications. Mr. Carter was freed; Mr. Artis had been released on parole in 1981.

When the prosecution’s attempts to reinstate the convictions were rejected by a federal appeals court and by the Supreme Court, the charges against Mr. Carter and Mr. Artis were formally dismissed in 1988, 22 years after the original indictments.

During his second imprisonment in the case his wife had sued for divorce, after learning that he had had an affair with a supporter while he was free on bail awaiting trial.

Information about his survivors could not immediately be learned.

On his final release from prison, Mr. Carter — with a full crop of curly hair, clean-shaven and wearing thick eyeglasses — moved to Toronto, where he lived with a secretive Canadian commune and married the head of it, Lisa Peters. He ended relations with her and the commune in the mid-1990s.

He founded Innocence International in 2004 and lectured about inequities in America’s criminal justice system. His former co-defendant, Mr. Artis, joined the organization. In 2011 he published an autobiography, “Eye of the Hurricane: My Path From Darkness to Freedom,” written with Ken Klonsky and with a foreword by Nelson Mandela.

In his last weeks he campaigned for the exoneration of David McCallum, a Brooklyn man who has been in prison since 1985 on murder charges. In an opinion article published by The Daily News on Feb. 21, 2014, headlined “Hurricane Carter’s Dying Wish,” he asked that Mr. McCallum “be granted a full hearing” by Brooklyn’s new district attorney, Kenneth P. Thompson.

“Just as my own verdict ‘was predicated on racism rather than reason and on concealment rather than disclosure,’ as Sarokin wrote, so too was McCallum’s,” Mr. Carter wrote.

He added: “If I find a heaven after this life, I’ll be quite surprised. In my own years on this planet, though, I lived in hell for the first 49 years, and have been in heaven for the past 28 years.

“To live in a world where truth matters and justice, however late, really happens, that world would be heaven enough for us all.”

*****

Rubin "Hurricane" Carter (May 6, 1937 – April 20, 2014) was an American middleweight boxer who was wrongly convicted of murder and later freed via a petition of habeas corpus after spending almost 20 years in prison.

In 1966, police arrested both Carter and friend John Artis for a triple-homicide committed in the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey. Police stopped Carter's car and brought him and Artis, also in the car, to the scene of the crime. On searching the car, the police found ammunition that fit the weapons used in the murder. Police took no fingerprints at the crime scene and lacked the facilities to conduct a paraffin test for gunshot residue. Carter and Artis were tried and convicted twice (1967 and 1976) for the murders, but after the second conviction was overturned in 1985, prosecutors chose not to try the case for a third time.

Carter's autobiography, titled The Sixteenth Round, was published in 1975 by Warner Books. The story inspired the 1975 Bob Dylan song "Hurricane" and the 1999 film The Hurricane (with Denzel Washington playing Carter). From 1993 to 2005, Carter served as executive director of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted.

*****

Rubin "Hurricane" Carter (May 6, 1937 – April 20, 2014) was an American middleweight boxer who was wrongly convicted of murder[1] and later freed via a petition of habeas corpus after spending almost 20 years in prison.

In 1966, police arrested both Carter and friend John Artis for a triple-homicide committed in the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey. Police stopped Carter's car and brought him and Artis, also in the car, to the scene of the crime. On searching the car, the police found ammunition that fit the weapons used in the murder. [2] Police took nofingerprints at the crime scene and lacked the facilities to conduct a paraffin test for gunshot residue. Carter and Artis were tried and convicted twice (1967 and 1976) for the murders, but after the second conviction was overturned in 1985, prosecutors chose not to try the case for a third time.

Carter's autobiography, titled The Sixteenth Round, was published in 1975 by Warner Books. The story inspired the 1975 Bob Dylan song "Hurricane" and the 1999 film The Hurricane (with Denzel Washington playing Carter). From 1993 to 2005, Carter served as executive director of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted.

Contents

[hide]Early life

Carter was born in Clifton, New Jersey, the fourth of seven children.[3] He acquired a criminal record and was sentenced to a juvenile reformatory for assault, having stabbed a man when he was 11.[4] Carter escaped from the reformatory in 1954 and joined the Army.[3] A few months after completing infantry basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, he was sent to West Germany.[5] While in Germany, Carter began to box for the United States Army.[5]

In May 1956, he received an "Unfitness" discharge, well before the end of his three-year term of enlistment.[6] He was arrested less than a month later for his escape from the Jamesburg Home for Boys. After his return to New Jersey, Carter was picked up by authorities and sentenced to an additional nine months, five of which he served in Annandale prison. Shortly after being released, Carter committed a series of muggings, including assault and robbery of a middle-aged black woman. He pleaded guilty to the charges and was imprisoned for the next four years in East Jersey State Prison (a maximum-security facility in Avenel, New Jersey, formerly Rahway State Prison) and in Trenton State Prison.[6]

Boxing career

After his release from prison in September 1961, Carter became a professional boxer.[7] At 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m), Carter was shorter than the average middleweight, but he fought all of his professional career at 155–160 lb (70–72.6 kg). His aggressive style and punching power (resulting in many early-round knockouts) drew attention, establishing him as a crowd favorite and earning him the nickname "Hurricane." After he defeated a number of middleweight contenders—such as Florentino Fernandez, Holley Mims, Gomeo Brennan, and George Benton—the boxing world took notice. The Ring first listed him as one of its "Top 10" middleweight contenders in July 1963.[citation needed]

He fought six times in 1963, winning four bouts and losing two.[7] He remained ranked in the lower part of the top 10 until December 20, when he surprised the boxing world by flooring past and future world champion Emile Griffith twice in the first round and scoring a technical knockout.[citation needed] That win resulted in The Ring's ranking of Carter as the number three contender for Joey Giardello's world middleweight title. Carter won two more fights (one a decision over future heavyweightchampion Jimmy Ellis) in 1964, before meeting Giardello in Philadelphia for a 15-round championship match on December 14. Carter fought well in the early rounds, landing a few solid rights to the head and staggering Giardello in the fourth, but failed to follow them up, and Giardello took control of the fight in the fifth round. The judges awarded Giardello a unanimous decision.[citation needed] Carter felt in retrospect that he lost by not bringing the fight to the champion.[8]

After that fight, Carter's standing as a contender—as reflected by his ranking in The Ring—began to decline. He fought nine times in 1965, but lost three of four fights against top contenders (Luis Manuel Rodríguez, Dick Tiger, and Harry Scott).[7]Tiger, in particular, floored Carter three times in their match. "It was," Carter said, "the worst beating that I took in my life—inside or outside the ring."[9] During his visit to London (to fight Scott) Carter was involved in an incident in which a shot was fired in his hotel room.[10]

Carter's career record in boxing was 27 wins, 12 losses, and one draw in 40 fights, with 19 total knockouts (8 KOs and 11 TKOs).[11] He received an honorary championship title belt from the World Boxing Council in 1993 (as did Joey Giardello at the same banquet) and was later inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame.[7]

Homicides

On June 17, 1966, at approximately 2:30 a.m., two males entered the Lafayette Bar and Grill at East 18th Street at Lafayette Street in Paterson, New Jersey, and started shooting.[12] The bartender, James Oliver, and a male customer, Fred Nauyoks, were killed instantly. A severely wounded female customer, Hazel Tanis, died almost a month later, having been shot in the throat, stomach, intestine, spleen and left lung, and having her arm shattered by shotgun pellets. A third customer, Willie Marins, survived the attack, despite a gunshot wound to the head that cost him the sight in one eye. During questioning, both Marins and Tanis told police that the shooters had been black males, though neither identified Carter or John Artis.[citation needed]

Petty criminal Alfred Bello, who had been near the Lafayette that night to burglarize a factory, was an eyewitness. Bello later testified that he was approaching the Lafayette when two black males—one carrying a shotgun, the other a pistol—came around the corner walking towards him.[13] He ran from them, and they got into a white car that was double-parked near the Lafayette.[12]

Bello was one of the first people on the scene of the shootings, as was Patricia Graham (later Patricia Valentine), a resident on the second floor (above the Lafayette Bar and Grill). Graham told the police that she saw two black males get into a white car and drive westbound.[citation needed] Another neighbor, Ronald Ruggiero, also heard the shots, and said that, from his window, he saw Alfred Bello running west on Lafayette Street toward 16th Street. He then heard the screech of tires and saw a white car shoot past, heading west, with two black males in the front seat.[citation needed] Both Bello and Valentine gave police a description of the car that was the same. Valentine's testimony regarding the car having lights lit up like butterflies, which Carter's did not have, changed when she testified during the second trial.[14]In response, the prosecution theorized that the dissimilarity perceived in Valentine's description was the result of a misreading of a court transcript by the defense.[15]

Investigation, indictment and first conviction

Hours before the triple murder, Carter was searching for guns that he had lost a year earlier.[16] Carter was driving a white Dodge Polara, which was notable for its butterfly taillights and out-of-state license plate with blue background and gold lettering.[17] Ten minutes after the murder, police stopped Carter's car. The police, not yet aware of the description of the getaway car, let Carter go.[18] Minutes later, the same police officers solicited a description of the getaway car from eyewitness Al Bello. He described the car as white with “a geometric design, sort of a butterfly type design in the back of the car”, and as bearing out-of-state license plates with blue background and orange lettering.[19] On hearing his description, the police realized that Al Bello was describing the car that they had only moments earlier let go. [17]

When police found Carter's car they stopped it and brought Carter and another occupant, John Artis, to the scene about 31 minutes after the incident. Police took nofingerprints at the crime scene, and lacked the facilities to test Carter and Artis for gunshot residue.[citation needed]

On searching the car about 45 minutes later, Detective Emil DiRobbio found a live .32 caliber pistol round under the front passenger seat and a 12-gauge shotgunshell in the trunk. Ballistics later established that the murder weapons had been a .32 caliber pistol and a 12-gauge shotgun.[13] The defense later raised questions about this evidence, as it was not logged with a property clerk until five days after the murders.[20] The prosecution responded to this line of questioning by producing a report lodged 75 minutes after the murders that documents the presence of the 32. caliber pistol round and 12-gauge shotgun shell.[21] The defense was able to show that the bullet found in the Carter car was brass cased, rather than copper coated like those found at the Lafayette Bar, and that the shotgun shell found in the Carter car was an older model, with a different wad and color.[22] In response, the prosecution argued that the metal and make of the retrieved ammunition was meaningless because the ammunition found at the crime scene was also dissimilar. Furthermore, the ammunition found in the car was usable by the murder weapons.[23]

Police took Carter and Artis to police headquarters and questioned them. Witnesses did not identify them as the killers, and they were released.[5] Carter and Artis voluntarily appeared before a grand jury, which did not return an indictment.[22]

Several months later, Bello disclosed to the police that he had an accomplice during the attempted burglary, one Arthur Dexter Bradley. On further questioning, Bello and Bradley both identified Carter as one of the two males they had seen carrying weapons outside the bar the night of the murders. Bello also identified Artis as the other. Based on this additional evidence, Carter and Artis were arrested and indicted.[24]

At the 1967 trial, Carter was represented by well-known attorney Raymond A. Brown.[25] Brown focused on inconsistencies in some of the descriptions given by eyewitnesses Marins and Bello.[26] The defense also produced a number of alibi witnesses who testified that Carter and Artis had been in the Nite Spot (a nearby bar) at about the time of the shootings.[13] Both men were convicted. Prosecutors sought the death penalty, but jurors recommended that each defendant receive a life sentence for each murder. Judge Samuel Larner imposed two consecutive and one concurrent life sentence on Carter, and three concurrent life sentences on Artis.[citation needed]

In 1974, Bello and Bradley recanted their identifications of Carter and Artis, and these recantations were used as the basis for a motion for a new trial. Judge Samuel Larner denied the motion on December 11, saying that the recantations "lacked the ring of truth."[27]

Despite Larner's ruling, Madison Avenue advertising guru George Lois organized a campaign on Carter's behalf, which led to increasing public support for a retrial or pardon. Muhammad Ali lent his support to the campaign, and Bob Dylan co-wrote (with Jacques Levy) and performed a song called "Hurricane" (1975), which declared that Carter was innocent. In 1975 Dylan performed the song at a concert at Trenton State Prison, where Carter was temporarily an inmate.[citation needed]

However, during the hearing on the recantations, defense attorneys also argued that Bello and Bradley had lied during the 1967 trial, telling the jurors that they had made only certain narrow, limited deals with prosecutors in exchange for their trial testimony. A detective taped one interrogation of Bello in 1966, and when it was played during the recantation hearing, defense attorneys argued that the tape revealed promises beyond what Bello had testified to. If so, prosecutors had either had a Brady obligation to disclose this additional exculpatory evidence, or a duty to disclose the fact that their witnesses had lied on the stand.[citation needed]

Larner denied this second argument as well, but the New Jersey Supreme Court unanimously held that the evidence of various deals made between the prosecution and witnesses Bello and Bradley should have been disclosed to the defense before or during the 1967 trial as this could have "affected the jury's evaluation of the credibility" of the eyewitnesses. "The defendants' right to a fair trial was substantially prejudiced," said Justice Mark Sullivan.[13] The court set aside the original convictions and granted Carter and Artis a new trial.[citation needed]

Despite the difficulties of prosecuting a ten-year-old case, Prosecutor Burrell Ives Humphreys decided to try Carter and Artis again. To ensure, as best he could, that he did not use perjured testimony to obtain a conviction, Humphreys had Bello polygraphed—once by Leonard H. Harrelson and a second time by Richard Arther, both well-known and respected experts in the field.[citation needed] Both men concluded that Bello was telling the truth when he said that he had seen Carter outside the Lafayette immediately after the murders.[citation needed]

However, Harrelson also reported orally that Bello had been inside the bar shortly before and at the time of the shooting, a conclusion that contradicted Bello's 1967 trial testimony.[28] Despite this oral report, Harrelson's subsequent written report stated that Bello's 1967 testimony had been truthful, the polygraphist apparently unaware that in 1967, Bello testified that he had been on the street at the time of the shooting.[28]

Second conviction and appeal

During the new trial, Alfred Bello repeated his 1967 testimony, identifying Carter and Artis as the two armed men he had seen outside the Lafayette Grill. Bradley refused to cooperate with prosecutors, and neither prosecution nor defense called him as a witness.[citation needed]

The defense responded with testimony from multiple witnesses who identified Carter at the locations he claimed to be at when the murders happened.[29] Defense witness Fred Hogan—whose efforts had led to the discredited recantations of Bello and Bradley—dealt the defense yet another blow. Though Hogan denied offering any bribes or inducements to Bello,[30] Judge Bruno Leopizzi forced him to produce his original handwritten notes on his conversations with Bello.[citation needed]

The court also heard testimony from a Carter associate that Passaic County prosecutors had tried to pressure her into testifying against Carter. Prosecutors denied the charge.[31] After deliberating for almost nine hours, the jury again found Carter and Artis guilty of the murders. Judge Leopizzi re-imposed the same sentences on both men: a double life sentence for Carter, a single life sentence for Artis.[citation needed]

Artis was paroled in 1981.[32] Carter's attorneys continued to appeal. In 1982, the Supreme Court of New Jersey affirmed his convictions (4–3). While the justices felt that the prosecutors should have disclosed Harrelson's oral opinion (about Bello's location at the time of the murders) to the defense, only a minority thought this was material. The majority thus concluded that the prosecution had not withheld information that the Brady disclosure law required that they provide to the defense.[33]

According to Carolyn Kelley, a 61-year-old from Newark working as a bail bondswoman in 1975, she was asked to get involved in the effort to win a new trial for Carter. She devoted more than a year to raising funds for Carter. Carter's appeal was upheld. In March 1976, Carter was released on bail to await a new trial. A few weeks later, Kelley said the boxer beat her into unconsciousness in his hotel room during a meeting she sought with him over affairs relating to her involvement with his cause. Rumors of the beating got out. Finally, Chuck Stone, a columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News, broke the story of the alleged beating in a front-page article. After Stone's column ran, the alleged beating became a national story. Carter's celebrity support melted away.[34] Mae Thelma Basket, whom Carter had married in 1963,[4] divorced him after their second child was born, because she found out that he had been unfaithful to her.[35]

Federal court action

Three years later, Carter's attorneys filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court. In 1985, Judge Haddon Lee Sarokin of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey granted the writ, noting that the prosecution had been "predicated upon an appeal to racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure," and set aside the convictions.[22] Carter, 48 years old, was freed without bail in November 1985.[12]

Prosecutors appealed Sarokin's ruling to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and filed a motion with the court to return Carter to prison pending the outcome of the appeal.[36][37] The court denied this motion and eventually upheld Sarokin's opinion, affirming his Brady analysis without commenting on his other rationale.[38]

The prosecutors appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.[12][39]

Prosecutors therefore could have tried Carter (and Artis) a third time, but decided not to, and filed a motion to dismiss the original indictments. "It is just not legally feasible to sustain a prosecution, and not practical after almost 22 years to be trying anyone," said New Jersey Attorney General W. Cary Edwards. Acting Passaic County Prosecutor John P. Goceljak said several factors made a retrial impossible, including Bello's "current unreliability" as a witness and the unavailability of other witnesses. Goceljak also doubted whether the prosecution could reintroduce the racially motivated crime theory due to the federal court rulings.[40] A judge granted the motion to dismiss, bringing an end to the legal proceedings.[41]

Aftermath

Carter lived in Toronto, Ontario, and was executive director of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted (AIDWYC) from 1993 until 2005. Carter resigned when the AIDWYC declined to support Carter's protest of the appointment (to a judgeship) of Susan MacLean, who was the prosecutor of Canadian Guy Paul Morin,[42] who served ten years in prison for rape and murder until exonerated by DNA evidence.[43]

Carter's second marriage was to Lisa Peters. The couple separated later.[4]

In 1996 Carter, then 59, was arrested when Toronto police mistakenly identified him as a suspect in his thirties believed to have sold drugs to an undercover officer. He was released after the police realized their error.[44]

Carter often served as a motivational speaker. On October 14, 2005, he received two honorary Doctorates of Law, one from York University (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and one from Griffith University (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia), in recognition of his work with AIDWYC and the Innocence Project. Carter received the Abolition Award from Death Penalty Focus in 1996.[citation needed]

Prostate cancer and death

In March 2012, while attending the International Justice Conference in Burswood, Western Australia, Carter revealed that he had terminal prostate cancer.[45] At the time, doctors gave him between three and six months to live. Beginning shortly after that time, John Artis lived with and cared for Carter,[46] and on April 20, 2014, he confirmed that Carter had succumbed to his illness.[47]

In the months leading up to his death, Carter worked for the exoneration of David McCallum, a Brooklyn man who has been incarcerated since 1985 on charges of murder. [48] Two months before his death, Carter published "Hurricane Carter's Dying Wish," an opinion piece in the New York Daily News, in which he asked for an independent review of McCallum's conviction. "I request only that McCallum be granted a full hearing by the Brooklyn conviction integrity unit, now under the auspices of the new district attorney, Ken Thompson. Knowing what I do, I am certain that when the facts are brought to light, Thompson will recommend his immediate release ... Just as my own verdict 'was predicated on racism rather than reason and on concealment rather than disclosure,' as Sarokin wrote, so too was McCallum’s," Carter wrote. [49]

Popular culture

Carter's story inspired:

- The 1975 Bob Dylan song "Hurricane"; Carter also appeared as himself in Dylan's 1978 movie Renaldo and Clara.[50]

- Nelson Algren's 1983 novel The Devil's Stocking.[51]

- The Norman Jewison 1999 feature film The Hurricane, starring Denzel Washington in the lead role about Rubin Carter's accusation, trials, and time spent in prison. Carter later discussed at a lecture how he fell in love with Washington's portrayal of him during auditions for The Hurricane, noting that boxer Marvin Hagler and actors Wesley Snipes and Samuel L. Jackson all vied for the role.[52]

- The Michael Franti and Spearhead song from 2001's album Stay Human entitled "Love'll Set Me Free" is also about Carter. The song's lyrics also include a paraphrased quotation from the Carter trials: "I ain't tryin' to appeal to just your mind/Just little part of your humanity." The words "Love like a Hurricane" in its lyrics also refer to Carter.[citation needed]

Professional boxing record

| 27 Wins (19 knockouts, 8 decisions), 12 Losses (1 knockout, 11 decisions), 1 Draw [53] | |||||||

| Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round | Date | Location | Notes |

| Loss | 52–13–3 | PTS | 10 | 06/08/1966 | |||

| Draw | 18–4 | PTS | 10 | 08/03/1966 | |||

| Win | 37–14–3 | KO | 8 | 26/02/1966 | |||

| Loss | 59–16–2 | PTS | 10 | 25/01/1966 | |||

| Loss | 25–9 | SD | 10 | 18/01/1966 | 44–47, 45–47, 47–44. | ||

| Win | 18–3 | SD | 10 | 08/01/1966 | |||

| Win | 45–6–1 | TKO | 2 | 18/09/1965 | |||

| Loss | 63–4 | UD | 10 | 26/08/1965 | 3–7, 2–7, 4–5. | ||

| Win | 21–1–1 | TKO | 1 | 14/07/1965 | Referee stopped the bout at 1:26 of the first round. | ||

| Loss | 50–16–3 | UD | 10 | 20/05/1965 | 1–9, 1–8, 2–6. | ||

| Win | 18–23–6 | TKO | 9 | 30/04/1965 | |||

| Loss | 22–15–4 | PTS | 10 | 20/04/1965 | |||

| Win | 22–14–4 | TKO | 9 | 09/03/1965 | |||

| Win | 20–11–7 | KO | 10 | 22/02/1965 | |||

| Loss | 57–4 | UD | 10 | 12/02/1965 | 3–6, 3–7, 3–7. | ||

| Loss | 96–24–8 | UD | 15 | 14/12/1964 | WBC/WBA World Middleweight Titles. 66–72, 66–71, 67–70. | ||

| Win | 8–3–1 | TKO | 1 | 24/06/1964 | Referee stopped the bout at 1:54 of the first round. | ||

| Win | 14–2 | UD | 10 | 28/02/1964 | 7–2, 6–3, 7–3. | ||

| Win | 38–4 | TKO | 1 | 20/12/1963 | Referee stopped the bout at 2:13 of the first round. | ||

| Loss | 36–1 | SD | 10 | 25/10/1963 | 4–5, 5–4, 4–6. | ||

| Win | 38–4–3 | UD | 10 | 14/09/1963 | 50–40, 50–41, 49–45. | ||

| Win | 48–7–1 | SD | 10 | 25/05/1963 | 4–5, 6–4, 7–2. | ||

| Loss | 23–7–1 | TKO | 6 | 30/03/1963 | |||

| Win | 52–7–5 | UD | 10 | 02/02/1963 | 9–1, 8–1, 7–3. | ||

| Win | 59–23–6 | UD | 10 | 22/12/1962 | 6–3, 6–3, 7–3. | ||

| Win | 31–5 | KO | 1 | 27/10/1962 | Fernandez knocked out at 1:09 of the first round. | ||

| Win | 22–20–2 | TKO | 5 | 08/10/1962 | Referee stopped the bout at 0:42 of the fifth round. | ||

| Win | 25–10–1 | TKO | 2 | 04/08/1962 | Referee stopped the bout at 2:17 of the second round. | ||

| Loss | 24–10–1 | UD | 8 | 23/06/1962 | |||

| Win | 53–20–5 | TKO | 3 | 21/05/1962 | |||

| Win | 8–4–1 | TKO | 2 | 30/04/1962 | |||

| Win | 13–2 | TKO | 1 | 16/04/1962 | Referee stopped the bout at 1:05 of the first round. | ||

| Win | 2–8 | KO | 3 | 16/03/1962 | |||

| Win | 3–9–2 | KO | 1 | 28/02/1962 | |||

| Win | 5–8 | KO | 1 | 14/02/1962 | |||

| Loss | 9–3 | PTS | 6 | 19/01/1962 | |||

| Win | 7–2 | PTS | 4 | 17/11/1961 | |||

| Win | 1–0 | TKO | 1 | 24/10/1961 | |||

| Win | 1–0–1 | KO | 2 | 11/10/1961 | |||

| Win | 1–0 | SD | 4 | 22/09/1961 | |||

No comments:

Post a Comment