Benedict of Nursia (Saint Benedict)

"Listen carefully to the master's instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart." [Prologue to the Rule of Saint Benedict] (01/22/2023)

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

St. Benedict (born c. 480 ce, Nursia [Italy]—died c. 547, Monte Cassino; feast day July 11, formerly March 21) was the founder of the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino and father of Western monasticism; the Rule that he established became the norm for monastic living throughout Europe. In 1964, in view of the work of monks following the Benedictine Rule in the evangelization and civilization of so many European countries in the Middle Ages, Pope Paul VI proclaimed him the patron saint of all Europe.

Life

The only recognized authority for the facts of Benedict’s life is book 2 of the Dialogues of St. Gregory I, who said that he had obtained his information from four of Benedict’s disciples. Though Gregory’s work includes many signs and wonders, his outline of Benedict’s life may be accepted as historical. He gives no dates, however. Benedict was born of good family and was sent by his parents to Roman schools. His life spanned the decades in which the decayed imperial city became the Rome of the medieval papacy. In Benedict’s youth, Rome under Theodoric still retained vestiges of the old administrative and governmental system, with a Senate and consuls. In 546 Rome was sacked and emptied of inhabitants by the Gothic king Totila, and, when the attempt of Emperor Justinian I to reconquer and hold Italy failed, the papacy filled the administrative vacuum and shortly thereafter became the sovereign power of a small Italian dominion virtually independent of the Eastern Empire.

Benedict thus served as a link between the monasticism of the East and the new age that was dawning. Shocked by the licentiousness of Rome, he retired as a young man to Enfide (modern Affile) in the Simbruinian hills and later to a cave in the rocks beside the lake then existing near the ruins of Nero’s palace above Subiaco, 64 km (40 miles) east of Rome in the foothills of the Abruzzi. There he lived alone for three years, furnished with food and monastic garb by Romanus, a monk of one of the numerous monasteries nearby.

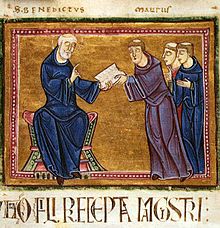

When the fame of his sanctity spread, Benedict was persuaded to become abbot of one of these monasteries. His reforming zeal was resisted, however, and an attempt was made to poison him. He returned to his cave, but again disciples flocked to him, and he founded 12 monasteries, each with 12 monks, with himself in general control of all. Patricians and senators of Rome offered their sons to become monks under his care, and from these novices came two of his best-known disciples, Maurus and Placid. Later, disturbed by the intrigues of a neighbouring priest, he left the area, while the 12 monasteries continued in existence.

A few disciples followed Benedict south, where he settled on the summit of a hill rising steeply above Cassino, halfway between Rome and Naples. The district was still largely pagan, but the people were converted by his preaching. His sister Scholastica, who came to live nearby as the head of a nunnery, died shortly before her brother. The only certain date in Benedict’s life is given by a visit from the Gothic king Totila about 542. Benedict’s feast day is kept by monks on March 21, the traditional day of his death, and by the Roman Catholic Church in Europe on July 11.

Benedict’s character, as Gregory points out, must be discovered from his Rule, and the impression given there is of a wise and mature sanctity, authoritative but fatherly, and firm but loving. It is that of a spiritual master, fitted and accustomed to rule and guide others, having himself found his peace in the acceptance of Christ.

Rule of St. Benedict

Gregory, in his only reference to the Rule, described it as clear in language and outstanding in its discretion. Benedict had begun his monastic life as a hermit, but he had come to see the difficulties and spiritual dangers of a solitary life, even though he continued to regard it as the crown of the monastic life for a mature and experienced spirit. His Rule is concerned with a life spent wholly in community, and among his contributions to the practices of the monastic life none is more important than his establishment of a full year’s probation, followed by a solemn vow of obedience to the Rule as mediated by the abbot of the monastery to which the monk vowed a lifelong residence.

On the constitutional level, Benedict’s supreme achievement was to provide a succinct and complete directory for the government and the spiritual and material well-being of a monastery. The abbot, elected for life by his monks, maintains supreme power and in all normal circumstances is accountable to no one. He should seek counsel of the seniors or of the whole body but is not bound by their advice. He is bound only by the law of God and the Rule, but he is continually advised that he must answer for his monks, as well as for himself, at the judgment seat of God. He appoints his own officials—prior, cellarer (steward), novice master, guest master, and the rest—and controls all the activities of individuals and the organizations of the common life. Ownership, even of the smallest thing, is forbidden. The ordering of the offices for the canonical hours (daily services) is laid down with precision. Novices, guests, the sick, readers, cooks, servers, and porters all receive attention, and punishments for faults are set out in detail.

Remarkable as is this careful and comprehensive arrangement, the spiritual and human counsel given generously throughout the Rule is uniquely noteworthy among all the monastic and religious rules of the Middle Ages. Benedict’s advice to the abbot and to the cellarer, and his instructions on humility, silence, and obedience have become part of the spiritual treasury of the church, from which not only monastic bodies but also legislators of various institutions have drawn inspiration.

St. Benedict also displayed a spirit of moderation. His monks are allowed clothes suited to the climate, sufficient food (with no specified fasting apart from the times observed by the Roman church), and sufficient sleep (7 1/2–8 hours). The working day is divided into three roughly equal portions: five to six hours of liturgical and other prayer; five hours of manual work, whether domestic work, craft work, garden work, or fieldwork; and four hours reading of the Scriptures and spiritual writings. This balance of prayer, work, and study is another of Benedict’s legacies.

All work was directed to making the monastery self-sufficient and self-contained; intellectual, literary, and artistic pursuits were not envisaged, but the presence of boys to be educated and the current needs of the monastery for service books, Bibles, and the writings of the Church Fathers implied much time spent in teaching and in copying manuscripts. Eventually Benedict’s plan for an ideal abbey was circulated to religious orders throughout Europe, and abbeys were generally built in accord with it in subsequent centuries.

Benedict’s discretion is manifested in his repeated allowances for differences of treatment according to age, capabilities, dispositions, needs, and spiritual stature; beyond this is the striking humanity of his frank allowance for weaknesses and failure, of his compassion for the physically weak, and of his mingling of spiritual with purely practical counsel. In the course of time this discretion has occasionally been abused in the defense of comfort and self-indulgence, but readers of the Rule can hardly fail to note the call to a full and exact observance of the counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Until 1938 the Rule had been considered as a personal achievement of St. Benedict, though it had always been recognized that he freely used the writings of the Desert Fathers, of St. Augustine of Hippo, and above all of St. John Cassian. In that year, however, an opinion suggesting that an anonymous document, the “Rule of the Master” (Regula magistri)—previously assumed to have plagiarized part of the Rule—was in fact one of the sources used by St. Benedict, provoked a lively debate. Though absolute certainty has not yet been reached, a majority of competent scholars favour the earlier composition of the “Rule of the Master.” If this is accepted, about one-third of Benedict’s Rule (if the formal liturgical chapters are excluded) is derived from the Master. This portion contains the prologue and the chapters on humility, obedience, and the abbot, which are among the most familiar and admired sections of the Rule.

Yet, even if this be so, the Rule that imposed itself all over Europe by virtue of its excellence alone was not the long, rambling, and often idiosyncratic “Rule of the Master.” It was the Rule of St. Benedict, derived from various and disparate sources, that provided for the monastic way of life a directory, at once practical and spiritual, that continued in force after 1,500 years.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Benedict of Nursia (Latin: Benedictus Nursiae; Italian: Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March 480 – 21 March 547), often known as Saint Benedict, was an Italian Catholic monk. He is famed in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Lutheran Churches, the Anglican Communion, and Old Catholic Churches.[3][4] In 1964 Pope Paul VI declared Benedict a patron saint of Europe.[5]

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at Subiaco in present-day Lazio, Italy (about 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the east of Rome), before moving further south-east to Monte Cassino in the mountains of central Italy. The present-day Order of Saint Benedict emerged later and, moreover, is not an "order" as the term is commonly understood, but a confederation of autonomous congregations.[6]

Benedict's main achievement, his Rule of Saint Benedict, contains a set of rules for his monks to follow. Heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian (c. 360 – c. 435), it shows strong affinity with the earlier Rule of the Master, but it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (ἐπιείκεια, epieíkeia), which persuaded most Christian religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, Benedict's Rule became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason, Giuseppe Carletti regarded Benedict as the founder of Western Christian monasticism.[7]

Apart from a short poem attributed to Mark of Monte Cassino,[8] the only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, thought to have been written in 593,[9] although the authenticity of this work is disputed.[10]

Gregory's account of Benedict's life, however, is not a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his Dialogues, saying they are a kind of floretum (an anthology, literally, 'flowers') of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.[11]

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically anchored story of Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with him and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as Abbot of Monte Cassino, Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his Dialogues, Valentinianus, and Simplicius.

In Gregory's day, history was not recognised as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and historia was an account that summed up the findings of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered history.[12] Gregory's Dialogues, Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter,[a] is designed to teach spiritual lessons.[9]

He was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia,[9][13] the modern Norcia, in Umbria. If 480 is accepted as the year of his birth, the year of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home would be about 500. Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 20 at the time.

Benedict was sent to Rome to study, but was disappointed by the academic studies he encountered there. Seeking to flee the great city, he left with his nurse and settled in Enfide.[14] Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about forty miles from Rome[13] and two miles from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine on which it runs becomes steeper until a cave is reached, above this point the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in Benedict's day, 500 feet (150 m) below, lay the blue waters of a lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and gave him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years lived in this cave above the lake.[13]

Gregory tells little of Benedict's later life. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, Gregory states, served Benedict in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.[14]

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent".[10]: 3 The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Thus he left the group and went back to his cave at Subiaco.

There lived in the neighborhood a priest called Florentius who, moved by envy, tried to ruin him. He tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. Having failed by sending him poisonous bread, Florentius tried to seduce his monks with some prostitutes. To avoid further temptations, in about 530 Benedict left Subiaco.[15] He founded 12 monasteries in the vicinity of Subiaco, and, eventually, in 530 he founded the great Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, which lies on a hilltop between Rome and Naples.[16]

Benedict died of a fever at Monte Cassino not long after his sister, Scholastica, and was buried in the same tomb. According to tradition, this occurred on 21 March 547.[17] He was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964.[18] In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared him co-patron of Europe, together with Cyril and Methodius.[19] Furthermore, he is the patron saint of speleologists.[20] On the island of Tenerife (Spain) he is the patron saint of fields and farmers. An important romeria (Romería Regional de San Benito Abad) is held on this island in his honor, one of the most important in the country.[21]

In the pre-1970 General Roman Calendar, his feast is kept on 21 March, the day of his death according to some manuscripts of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum and that of Bede. Because on that date his liturgical memorial would always be impeded by the observance of Lent, the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar moved his memorial to 11 July, the date that appears in some Gallic liturgical books of the end of the 8th century as the feast commemorating his birth (Natalis S. Benedicti). There is some uncertainty about the origin of this feast.[22] Accordingly, on 21 March the Roman Martyrology mentions in a line and a half that it is Benedict's day of death and that his memorial is celebrated on 11 July, while on 11 July it devotes seven lines to speaking of him, and mentions the tradition that he died on 21 March.[23]

The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates Saint Benedict on 14 March.[24]

The Lutheran Churches celebrate the Feast of Saint Benedict on July 11.[4]

The Anglican Communion has no single universal calendar, but a provincial calendar of saints is published in each province. In almost all of these, Saint Benedict is commemorated on 11 July. Benedict is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 11 July.[25]

Benedict wrote the Rule for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The Rule comprises seventy-three short chapters. Its wisdom is twofold: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently).[16] More than half of the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the work of God (the "opus Dei"). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. Benedictine asceticism is known for its moderation.[26]

This devotional medal originally came from a cross in honor of Saint Benedict. On one side, the medal has an image of Saint Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin are the words "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials CSSML on the vertical bar which signify "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") and on the horizontal bar are the initials NDSMD which stand for "Non-Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide"). The initials CSPB stand for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of the Holy Father Benedict") and are located on the interior angles of the cross. Either the inscription "PAX" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" may be found at the top of the cross in most cases. Around the medal's margin on this side are the Vade Retro Satana initials VRSNSMV which stand for "Vade Retro Satana, Nonquam Suade Mihi Vana" ("Begone Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities") then a space followed by the initials SMQLIVB which signify "Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thine own poison").[27]

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of 23 December 1741 and 12 March 1742.[27]

Benedict has been also the motif of many collector's coins around the world. The Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued on 13 March 2002 is one of them.

The early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries."[28] In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that "with his life and work St Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture" and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman empire.[29]

Benedict contributed more than anyone else to the rise of monasticism in the West. His Rule was the foundational document for thousands of religious communities in the Middle Ages.[30] To this day, The Rule of St. Benedict is the most common and influential Rule used by monasteries and monks, more than 1,400 years after its writing.

A basilica was built upon the birthplace of Benedict and Scholastica in the 1400s. Ruins of their familial home were excavated from beneath the church and preserved. The earthquake of 30 October 2016 completely devastated the structure of the basilica, leaving only the front facade and altar standing.[31][32]

- See also Category:Paintings of Benedict of Nursia.

- Anthony the Great

- Scholastica (St. Benedict's sister)

- Benedict of Aniane

- Benedictine Order

- Camaldolese

- Hermit

- San Beneto

- Saint Benedict Medal

- Vade retro satana

- ^ For the various literary accounts, see Anonymous Monk of Whitby, The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, tr. B. Colgrave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 157, n. 110.

- ^ Lanzi, Fernando; Lanzi, Gioia (2004) [2003]. Saints and Their Symbols: Recog [Come riconoscere i santi]. Translated by O'Connell, Matthew J. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 218. ISBN 9780814629703. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Benedict of Nursia [...] Principal attributes: black monastic garb, staff, book with inscription: "Pray and Work."

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Barry, Patrick (1995). St. Benedict and Christianity in England. Gracewing Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780852443385.

- ^ a b Ramshaw, Gail (1983). Festivals and Commemorations in Evangelical Lutheran Worship (PDF). Augsburg Fortress. p. 299.

- ^ Barrely, Christine; Leblon, Saskia; Péraudin, Laure; Trieulet, Stéphane (23 March 2011) [2009]. "Benedict". The Little Book of Saints [Petit livre des saints]. Translated by Bell, Elizabeth. San Francisco: Chronicle Book. p. 34. ISBN 9780811877473. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Declared the patron saint of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI, Benedict is also the patron of farmers, peasants, and Italian architects.

- ^ Holder, Arthur G. (2009). Christian Spirituality: The Classics. Taylor & Francis. p. 70. ISBN 9780415776028. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

Today, tens of thousands of men and women throughout the world profess to live their lives according to Benedict's Rule. These men and women are associated with over two thousand Roman Catholic, Anglican, and ecumenical Benedictine monasteries on six continents.

- ^ Carletti, Giuseppe, Life of St. Benedict (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971).

- ^ "The Autumn Number 1921" (PDF). The Ampleforth Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Ford, Hugh. "St. Benedict of Norcia." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 3 Mar. 2014". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Life and Miracles of St. Benedict (Book II, Dialogues), tr. Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict , O.S.B. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. iv.

- ^ See Ildephonso Schuster, Saint Benedict and His Times, Gregory A. Roettger, tr. (London: B. Herder, 1951), p. 2.

- ^ See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, ed., Historiography in the Middle Ages (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Knowles, Michael David. "St. Benedict". Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ a b ""Saint Benedict, Abbot", Lives of Saints, John J. Crawley & Co., Inc". Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Bunson, M., Bunson, M., & Bunson, S., Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints (Huntington IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2014), p. 125.

- ^ a b "St Benedict of Nursia", the British Library

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Norcia". Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "St. Benedict of Norcia". Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ "Egregiae Virtutis". Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009. Apostolic letter of Pope John Paul II, 31 December 1980 (in Latin)

- ^ Brewer's dictionary of phrase & fable. Cassell. p.953

- ^ "Romería de San Benito Abad", Oficial de turismo de España

- ^ "Calendarium Romanum" (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), pp. 97 and 119

- ^ Martyrologium Romanum 199 (edito altera 2004); pages 188 and 361 of the 2001 edition (Libreria Editrice Vaticana ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3)

- ^ ""Orthodox Church in America: The Lives of the Saints, March 14th"". Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Saint Benedict", Franciscan Media

- ^ a b The Life of St Benedict Archived 20 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, by St. Gregory the Great, Rockford, IL: TAN Books, pp 60–62.

- ^ "Western Europe in the Middle Ages". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia" Homily given to a general audience at St. Peter's Square on Wednesday, 9 April 2008 "?". Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Stracke, Prof. J.R., "St. Benedict – Iconography", Augusta State University Archived 16 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Earthquake Blog - Monks of Norcia". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Bruton, F. B., & Lavanga, C., "Beer-Brewing Monks of Norcia Say Earthquake Destroys St. Benedict Basilica" Archived 8 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, NBC News, October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Gardner, Edmund G., ed. (1911). The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great. London and Boston: Philip Lee Warner, Publisher to the Medici Society Ltd. ISBN 9781889758947.

- "The Order of Saint Benedict". osb.org. (Institutional website of the Order of Saint Benedict)

- "Life and Miracles of Saint Benedict" (in English, Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 October 2004.

- "A Benedictine Oblate Priest – The Rule in Parish Life". Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries at Project Gutenberg, translated by Leonard J. Doyle

- "The Holy Rule of St. Benedict". Translated by Boniface Verheyen.

- Gregory the Great. "Life and Miracles of St Benedict". Dialogues. Vol. Book 2. pp. 51–101.

- Guéranger, Prosper (1880). "The Medal Or Cross of St. Benedict: Its Origin, Meaning, and Privileges".

- Works by Benedict of Nursia at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benedict of Nursia at the Internet Archive

- Works by Benedict of Nursia at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Saint Benedict of Norcia, Patron of Poison Sufferers, Monks, And Many More". Archived from the original on 21 April 2014.

- Marett-Crosby, A., ed., The Benedictine Handbook (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2003).

- Publications by and about Benedict of Nursia in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- "Saint Benedict of Norcia". Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- "Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica".

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Rule of Saint Benedict (Latin: Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin c. 530 by St. Benedict of Nursia (c. AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.[1]

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Rule is summed up in the motto of the Benedictine Confederation: pax ("peace") and the traditional ora et labora ("pray and work"). Compared to other precepts, the Rule provides a moderate path between individual zeal and formulaic institutionalism; because of this middle ground, it has been widely popular. Benedict's concerns were his views of the needs of monks in a community environment: namely, to establish due order, to foster an understanding of the relational nature of human beings, and to provide a spiritual father to support and strengthen the individual's ascetic effort and the spiritual growth that is required for the fulfillment of the human vocation, theosis.

The Rule of Saint Benedict has been used by Benedictines for 15 centuries, and thus St. Benedict is sometimes regarded as the founder of Western monasticism due to the reforming influence that his rules had on the then-current Catholic hierarchy.[2] There is, however, no evidence to suggest that Benedict intended to found a religious order in the modern sense, and it was not until the Late Middle Ages that mention was made of an "Order of Saint Benedict". His Rule was written as a guide for individual, autonomous communities, and all Benedictine Houses (and the Congregations in which they have grouped themselves) still remain self-governing. Advantages seen in retaining this unique Benedictine emphasis on autonomy include cultivating models of tightly bonded communities and contemplative lifestyles. Perceived disadvantages comprise geographical isolation from important activities in adjacent communities. Other perceived losses include inefficiency and lack of mobility in the service of others, and insufficient appeal to potential members. These different emphases emerged within the framework of the Rule in the course of history and are to some extent present within the Benedictine Confederation and the Cistercian Orders of the Common and the Strict Observance.

Christian monasticism first appeared in the Egyptian desert, before Benedict of Nursia. Under the inspiration of Saint Anthony the Great (251–356), ascetic monks led by Saint Pachomius (286–346) formed the first Christian monastic communities under what became known as an Abbot, from the Aramaic abba (father).[3]

Within a generation, both solitary as well as communal monasticism became very popular and spread outside of Egypt, first to Palestine and the Judean Desert and thence to Syria and North Africa. Saint Basil of Caesarea codified the precepts for these eastern monasteries in his Ascetic Rule, or Ascetica, which is still used today in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

In the West in about the year 500, Benedict became so upset by the immorality of society in Rome that he gave up his studies there, at age fourteen, and chose the life of an ascetic monk in the pursuit of personal holiness, living as a hermit in a cave near the rugged region of Subiaco. In time, setting an example with his zeal, he began to attract disciples. After considerable initial struggles with his first community at Subiaco, he eventually founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in 529, where he wrote his Rule near the end of his life.[4]

In chapter 73, Saint Benedict commends the Rule of Saint Basil and alludes to further authorities. He was probably aware of the Rule written by Pachomius (or attributed to him), and his Rule also shows influence by the Rule of St Augustine of Hippo and the writings of Saint John Cassian. Benedict's greatest debt, however, may be to the anonymous document known as the Rule of the Master, which Benedict seems to have radically excised, expanded, revised and corrected in the light of his own considerable experience and insight.[5] Saint Benedict's work expounded upon preconceived ideas that were present in the religious community only making minor changes more in line with the time period relevant to his system.[6][7]

The Rule was translated into Armenian by Nerses of Lampron in the 10th century and is used by the Armenian Catholic Mekhitarists today. It was also translated into Old English by Æthelwold.[8]

The Rule opens with a hortatory preface, drawing on the Admonitio ad filium spiritualem,[9] in which Saint Benedict sets forth the main principles of the religious life, viz.: the renunciation of one's own will and arming oneself "with the strong and noble weapons of obedience" under the banner of "the true King, Christ the Lord" (Prol. 3). He proposes to establish a "school for the Lord's service" (Prol. 45) in which the "way to salvation" (Prol. 48) shall be taught, so that by persevering in the monastery till death his disciples may "through patience share in the passion of Christ that [they] may deserve also to share in his Kingdom" (Prol. 50, passionibus Christi per patientiam participemur, ut et regno eius mereamur esse consortes; note: Latin passionibus and patientiam have the same root, cf. Fry, RB 1980, p.167).[10]

- Chapter 1 defines four kinds of monk:

- Cenobites, those "in a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot".

- Anchorites, or hermits, who, after long successful training in a monastery, are now coping single-handedly, with only God for their help.

Regula, 1495 - Sarabaites, living by twos and threes together or even alone, with no experience, rule and superior, and thus a law unto themselves.[10]

- Gyrovagues, wandering from one monastery to another, slaves to their own wills and appetites.[10]

- Chapter 2 describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot, forbids the abbot to make distinctions between persons in the monastery except for particular merit, and warns him that he will be answerable for the salvation of the souls in his care.[10]

- Chapter 3 ordains the calling of the brothers to council upon all affairs of importance to the community.[10]

- Chapter 4 lists 73 "tools for good work", "tools of the spiritual craft" for the "workshop" that is "the enclosure of the monastery and the stability in the community". These are essentially the duties of every Christian and are mainly Scriptural either in letter or in spirit.[10]

- Chapter 5 prescribes prompt, ungrudging, and absolute obedience to the superior in all things lawful,[10] "unhesitating obedience" being called the first step (Latin gradus) of humility.

- Chapter 6 recommends taciturnity (Latin taciturnitas), i.e. the state or quality of being reserved or reticent in conversation, in the use of speech.[10]

- Chapter 7 divides humility into twelve steps forming rungs in a ladder that leads to heaven:[10](1) Fear God; (2) Subordinate one's will to the will of God; (3) Be obedient to one's superior; (4) Be patient amid hardships; (5) Confess one's sins; (6) Accept the meanest of tasks, and hold oneself as a "worthless workman"; (7) Consider oneself "inferior to all"; (8) Follow examples set by superiors; (9) Do not speak until spoken to; (10) Do not readily laugh; (11) Speak simply and modestly; and (12) Express one's inward humility through bodily posture.

- Chapter 8–19 regulate the Divine Office, the Godly work to which "nothing is to be preferred", namely the eight canonical hours. Detailed arrangements are made for the number of Psalms, etc., to be recited in winter and summer, on Sundays, weekdays, Holy Days, and at other times.[10]

- Chapter 19 emphasizes the reverence owed to the omnipresent God.[10]

- Chapter 20 directs that prayer be made with heartfelt compunction rather than many words.[10] It should be prolonged only under the inspiration of divine grace, and in community always kept short and terminated at a sign from the superior.

- Chapter 21 regulates the appointment of a Dean over every ten monks.[10]

- Chapter 22 regulates the dormitory. Each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit, so as to be ready to rise without delay for the Divine Office at night; a candle (Latin "candela") shall burn in the dormitory throughout the night.[10]

- Chapters 23–29 specify a graduated scale of punishments for contumacy (refusal to obey authority), disobedience, pride, and other grave faults: first, private admonition; next, public reproof; then separation from the brothers at meals and elsewhere;[10] and finally excommunication (or in the case of those lacking understanding of what this means, corporal punishment instead).

- Chapter 30 directs that a wayward brother who has left the monastery must be received again, if he promises to make amends; but if he leaves again, and again, after his third departure all return is finally barred.[10]

- Chapters 31 & 32 order the appointment of officials to take charge of the goods of the monastery.[10]

- Chapter 33 forbids the private possession of anything without the leave of the abbot, who is, however, bound to supply all necessities.[10]

- Chapter 34 prescribes a just distribution of such things.[10]

- Chapter 35 arranges for the service in the kitchen by all monks in turn.[10]

- Chapters 36 & 37 address care of the sick, the old, and the young. They are to have certain dispensations from the strict Rule, chiefly in the matter of food.[10]

- Chapter 38 prescribes reading aloud during meals, which duty is to be performed by those who can do so with edification to the rest. Signs are to be used for whatever may be wanted at meals, so that no voice interrupts the reading. The reader eats with the servers after the rest have finished, but he is allowed a little food beforehand in order to lessen the fatigue of reading.[10]

- Chapters 39 & 40 regulate the quantity and quality of the food. Two meals a day are allowed, with two cooked dishes at each. Each monk is allowed a pound of bread and a hemina (about a quarter litre) of wine. The flesh of four-footed animals is prohibited except for the sick and the weak.[10]

- Chapter 41 prescribes the hours of the meals, which vary with the time of year.[10]

- Chapter 42 enjoins the reading of an edifying book in the evening, and orders strict silence after Compline.[10]

- Chapters 43–46 define penalties for minor faults, such as coming late to prayer or meals.[10]

- Chapter 47 requires the abbot to call the brothers to the "work of God" (Opus Dei) in choir, and to appoint chanters and readers.[10]

- Chapter 48 emphasizes the importance of daily manual labour appropriate to the ability of the monk. The duration of labour varies with the season but is never less than five hours a day.[10]

- Chapter 49 recommends some voluntary self-denial for Lent, with the abbot's sanction.[10]

- Chapters 50 & 51 contain rules for monks working in the fields or travelling. They are directed to join in spirit, as far as possible, with their brothers in the monastery at the regular hours of prayers.[10]

- Chapter 52 commands that the oratory be used for purposes of devotion only.[10]

- Chapter 53 deals with hospitality. Guests are to be met with due courtesy by the abbot or his deputy; during their stay they are to be under the special protection of an appointed monk; they are not to associate with the rest of the community except by special permission.[10]

- Chapter 54 forbids the monks to receive letters or gifts without the abbot's leave.[10]

- Chapter 55 says clothing is to be adequate and suited to the climate and locality, at the discretion of the abbot. It must be as plain and cheap as is consistent with due economy. Each monk is to have a change of clothes to allow for washing, and when travelling is to have clothes of better quality. Old clothes are to be given to the poor.[10]

- Chapter 56 directs the abbot to eat with the guests.[10]

- Chapter 57 enjoins humility on the craftsmen of the monastery, and if their work is for sale, it shall be rather below than above the current trade price.[10]

- Chapter 58 lays down rules for the admission of new members, which is not to be made too easy. The postulant first spends a short time as a guest; then he is admitted to the novitiate where his vocation is severely tested; during this time he is always free to leave. If after twelve months' probation he perseveres, he may promise before the whole community stabilitate sua et conversatione morum suorum et oboedientia – "stability, conversion of manners, and obedience". With this vow he binds himself for life to the monastery of his profession.[10]

- Chapter 59 describes the ceremony of indenturing young boys into the monastery and arranges certain financial arrangements for this.[10]

- Chapter 60 regulates the position of priests who join the community. They are to set an example of humility, and can only exercise their priestly functions by permission of the abbot.[10]

- Chapter 61 provides for the reception of foreign monks as guests, and for their admission to the community.[10]

- Chapter 62 deals with the ordination of priests from within the monastic community.

- Chapter 63 lays down that precedence in the community shall be determined by the date of admission, merit of life, or the appointment of the abbot.[10]

- Chapter 64 orders that the abbot be elected by his monks, and that he be chosen for his charity, zeal, and discretion.[10]

- Chapter 65 allows the appointment of a prior or deputy superior, but warns that he is to be entirely subject to the abbot and may be admonished, deposed, or expelled for misconduct.

- Chapter 66 appoints a porter, and recommends that each monastery be self-contained and avoid intercourse with the outer world.[10]

- Chapter 67 instructs monks how to behave on a journey.[10]

- Chapter 68 orders that all cheerfully try to do whatever is commanded, however apparently impossible it may seem.[10]

- Chapter 69 forbids the monks from defending one another.[10]

- Chapter 70 prohibits them from beating (Latin caedere) or excommunicating one another.[10]

- Chapter 71 encourages the brothers to be obedient not only to the abbot and his officials, but also to one another.[10]

- Chapter 72 briefly exhorts the monks to zeal and fraternal charity.[10]

- Chapter 73 is an epilogue; it declares that the Rule is not offered as an ideal of perfection, but merely as a means towards godliness, intended chiefly for beginners in the spiritual life.[10]

Saint Benedict's model for the monastic life was the family, with the abbot as father and all the monks as brothers. Priesthood was not initially an important part of Benedictine monasticism – monks used the services of their local priest. Because of this, almost all the Rule is applicable to communities of women under the authority of an abbess. This appeal to multiple groups would later make the Rule of Saint Benedict an integral set of guidelines for the development of the Christian faith.

Saint Benedict's Rule organises the monastic day into regular periods of communal and private prayer, sleep, spiritual reading, and manual labour – ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus, "that in all [things] God may be glorified" (cf. Rule ch. 57.9). In later centuries, intellectual work and teaching took the place of farming, crafts, or other forms of manual labour for many – if not most – Benedictines.

Traditionally, the daily life of the Benedictine revolved around the eight canonical hours. The monastic timetable, or Horarium, would begin at midnight with the service, or "office", of Matins (today also called the Office of Readings), followed by the morning office of Lauds at 3 am. Before the advent of wax candles in the 14th century, this office was said in the dark or with minimal lighting; and monks were expected to memorise everything. These services could be very long, sometimes lasting till dawn, but usually consisted of a chant, three antiphons, three psalms, and three lessons, along with celebrations of any local saints' days. Afterwards the monks would retire for a few hours of sleep and then rise at 6am to wash and attend the office of Prime. They then gathered in Chapter to receive instructions for the day and to attend to any judicial business. Then came private Mass or spiritual reading or work until 9am when the office of Terce was said, and then High Mass. At noon came the office of Sext and the midday meal. After a brief period of communal recreation, the monk could retire to rest until the office of None at 3pm. This was followed by farming and housekeeping work until after twilight, the evening prayer of Vespers at 6pm, then the night prayer of Compline at 9pm, and retiring to bed, before beginning the cycle again. In modern times, this timetable is often changed to accommodate any apostolate outside the monastic enclosure (e.g. the running of a school[11] or parish).

Many Benedictine Houses have a number of Oblates (secular) who are affiliated with them in prayer, having made a formal private promise (usually renewed annually) to follow the Rule of St Benedict in their private life as closely as their individual circumstances and prior commitments permit.

In recent years discussions have occasionally been held[by whom?] concerning the applicability of the principles and spirit of the Rule of Saint Benedict to the secular working environment.[12]

During the more than 1500 years of their existence, Benedictines have seen cycles of flourish and decline. Several reform movements sought more intense devotion to both the letter and spirit of the Rule of St Benedict, at least as they understood it. Examples include the Camaldolese, the Cistercians, the Trappists (a reform of the Cistercians), and the Sylvestrines.

Charlemagne had Benedict's Rule copied and distributed to encourage monks throughout western Europe to follow it as a standard. Beyond its religious influences, the Rule of St Benedict was one of the most important written works to shape medieval Europe, embodying the ideas of a written constitution and the rule of law. It also incorporated a degree of democracy in a non-democratic society, and dignified manual labor.

Although not stated explicitly in the rule, the motto Ora et labora is widely considered to be a shortform capturing the spirit of the rule.[13]

- Rule of Saint Augustine

- Rule of Saint Basil

- Benedictine rite

- Columban Rule

- Rule of the Master

- Rule of Saint Albert

- Latin Rule

- Customary (liturgy)

- ^ Vogüé, Adalbert de; Neufville, Jean (1972). La Règle de Saint Benoît. Les Éditions du Cerf.

- ^ Kardong, T. (2001). Saint Benedict and the Twelfth-Century Reformation. Cistercian Studies Quarterly, 36(3), 279.

- ^ "abbot". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Chambers, Mortimer (1974). The Western Experience. Knopf. p. 188. ISBN 0-394-31733-5.

- ^ "OSB. About the Rule of Saint Benedict by Abbot Primate Jerome Theisen OSB". Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Rule of St. Benedict". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ^ Zuidema, Jason (2012). "Understanding Decline and Renewal in the History of Life under Saint Benedict's Rule: Observations from Canada". Cistercian Studies Quarterly. 47: 456–469.

- ^ See Jacob Riyeff (trans.), The Old English Rule of Saint Benedict: with Related Old English Texts (Liturgical Press, 2017).

- ^ James Francis LePree, "Pseudo-Basil's De admonitio ad filium spiritualem: A New English Translation", The Heroic Age: A Journal of Early Medieval Northwestern Europe 13 (2010).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Rule of St. Benedict". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Rule of St. Benedict". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ^ Alcuin Deutsch, Educational principles in the Rule of St. Benedict. Collegeville, Minn., St. John's Abbey [1912].

- ^ Kleymann, Birgit; Malloch, Hedley (2010). "The rule of Saint Benedict and corporate management: Employing the whole person". Journal of Global Responsibility. 1 (2): 207–224. doi:10.1108/20412561011079362.

- ^ "Work Is Prayer: Not! by Terrence Kardong from Assumption Abbey Newsletter (Richardton, ND 58652). Volume 23, Number 4 (October 1995)". Retrieved 2010-07-07.

Notes

- R. W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages. Pelican, 1970

- Henry Mayr-Harting, The Venerable Bede, the Rule of St Benedict, and Social Class. Jarrow Lecture 1976; Jarrow: Rector of Jarrow, 1976. ISBN 0-903495-03-1

- Christopher Derrick, The Rule of Peace: St. Benedict and the European Future. Still River, Mass.: St. Bede's Publications. 2002. ISBN 978-0-932506-01-6

Benedictine Rule, regulation for monastic conduct as prescribed by the 6th-century monk St. Benedict of Nursia. The Rule is followed by the Order of St. Benedict, a Roman Catholic religious community of confederated congregations of monks, lay brothers, and nuns.

Overview

St. Benedict wrote his rule with his own abbey of Monte Cassino in mind. On the constitutional level, Benedict’s supreme achievement was to provide a succinct and complete directory for the government and the spiritual and material well-being of a monastery. The abbot, elected for life by his monks, maintains supreme power and in all normal circumstances is accountable to no one. He should seek counsel of the seniors or of the whole body but is not bound by their advice. He is bound only by the law of God and the Rule, but he is continually advised that he must answer for his monks, as well as for himself, at the judgment seat of God. He appoints his own officials—prior, cellarer (steward), novice master, guest master, and the rest—and controls all the activities of individuals and the organizations of the common life. Ownership, even of the smallest thing, is forbidden. The ordering of the offices for the canonical hours (daily services) is laid down with precision. Novices, guests, the sick, readers, cooks, servers, and porters all receive attention, and punishments for faults are set out in detail.

Remarkable as is this careful and comprehensive arrangement, the spiritual and human counsel given generously throughout the Rule is uniquely noteworthy among all the monastic and religious rules of the Middle Ages. Benedict’s advice to the abbot and to the cellarer and his instructions on humility, silence, and obedience have become part of the spiritual treasury of the church, from which not only monastic bodies but also legislators of various institutions have drawn inspiration.

St. Benedict also displayed a spirit of moderation. His monks are allowed clothes suited to the climate, sufficient food (with no specified fasting apart from the times observed by the Roman church), and sufficient sleep (seven and a half to eight hours). The working day is divided into three roughly equal portions: five to six hours of liturgical and other prayer; five hours of manual work, whether domestic work, craft work, garden work, or fieldwork; and four hours of reading the Scriptures and spiritual writings. This balance of prayer, work, and study is another of Benedict’s legacies.

All work was directed to making the monastery self-sufficient and self-contained; intellectual, literary, and artistic pursuits were not envisaged, but the presence of boys to be educated and the current needs of the monastery for service books, Bibles, and the writings of the Church Fathers implied much time spent in teaching and in copying manuscripts. Eventually, Benedict’s plan for an ideal abbey was circulated to religious orders throughout Europe, and abbeys were generally built in accord with it in subsequent centuries.

History and practice in Western monasticism

The Rule, which spread slowly in Italy and Gaul, provided a complete directory for both the government and the spiritual and material well-being of a monastery by carefully integrating prayer, manual labour, and study into a well-rounded daily routine. By the 7th century the rule had been applied to women, as nuns, whose patron was deemed St. Scholastica, sister of St. Benedict.

By the time of Charlemagne at the beginning of the 9th century, the Benedictine Rule had supplanted most other observances in northern and western Europe. During the five centuries following the death of Benedict, the monasteries multiplied both in size and in wealth. They were the chief repositories of learning and literature in western Europe and were also the principal educators. One of the most celebrated of Benedictine monasteries was the Burgundian Abbey of Cluny, founded as a reform house by William of Aquitaine in 910. The Cluniac reform was often imitated by other monasteries, and a succession of able abbots gradually built up throughout western Europe a great network of monasteries that followed the strict Cluniac customs and were under the direct jurisdiction of Cluny.

The great age of Benedictine predominance ended about the middle of the 12th century, and the history of the main line of Benedictine monasticism for the next three centuries was to be one of decline and decadence.

The 15th century saw the rise of a new Benedictine institution, the congregation. In 1424 the congregation of Santa Giustina of Padua instituted reforms that breathed new life into Benedictine monasticism. Superiors were elected for three years. Monks no longer took vows to a particular house but to the congregation. Further, ruling authority was concentrated in the annual general chapter or legislative meeting. This radical reform spread within a century to all the Benedictines of Italy and became known as the Cassinese Congregation. There were similar reforms throughout Europe. These reforms were confronted by the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Within a few years (1525–60) the monasteries and nunneries disappeared almost entirely from northern Europe and suffered greatly in France and central Europe. Benedictinism revived in France and Germany during the 17th century, however, and several congregations were founded, notably that of the male Maurists in France and the female Perpetual Adoration in Paris (1653) and Our Lady of Calvary (1617). Although the 18th century witnessed a new decline, from the middle of the 19th century Benedictine monasteries and nunneries again began to flourish. Foundations, including Solesmes, with its emphasis on the celebration of the liturgy, arose throughout Europe; monks and nuns returned to England; congregations were established in North and South America; and monasteries scattered all over the world. In the face of this revival, Pope Leo XIII desired to bring about some sort of unity among the traditionally independent Benedictines. In 1893 he created the office of abbot primate as head of the federation of autonomous congregations. This office, though unwelcome because of the Benedictine desire for autonomy, gradually developed in influence.

Until 1938 the Rule had been considered as a personal achievement of St. Benedict, though it had always been recognized that he freely used the writings of the Desert Fathers, of St. Augustine of Hippo, and above all of St. John Cassian. In that year, however, an opinion suggesting that an anonymous document, the “Rule of the Master” (Regula magistri)—previously assumed to have plagiarized part of the Rule—was in fact one of the sources used by St. Benedict provoked a lively debate. Though absolute certainty has not yet been reached, a majority of competent scholars favour the earlier composition of the “Rule of the Master.” If this is accepted, about one-third of Benedict’s Rule (if the formal liturgical chapters are excluded) is derived from the Master. This portion contains the prologue and the chapters on humility, obedience, and the abbot, which are among the most familiar and admired sections of the Rule.

Yet, even if this be so, the Rule that imposed itself all over Europe by virtue of its excellence alone was not the long, rambling, and often idiosyncratic “Rule of the Master.” It was the Rule of St. Benedict, derived from various and disparate sources, that provided for the monastic way of life a directory, at once practical and spiritual, that continued in force after 1,500 years.

In 1964, in view of the work of monks following the Benedictine Rule in the evangelization and civilization of so many European countries in the Middle Ages, Pope Paul VI proclaimed Benedict the patron saint of all Europe.

Benedictine, member of any of the confederated congregations of monks, lay brothers, and nuns who follow the rule of life of St. Benedict (c. 480–c. 547) and who are spiritual descendants of the traditional monastics of the early medieval centuries in Italy and Gaul. The Benedictines, strictly speaking, do not constitute a single religious order, because each monastery is autonomous.

St. Benedict wrote his rule, the so-called Benedictine Rule, c. 535–540 with his own abbey of Montecassino in mind. The rule, which spread slowly in Italy and Gaul, provided a complete directory for both the government and the spiritual and material well-being of a monastery by carefully integrating prayer, manual labour, and study into a well-rounded daily routine. By the 7th century the rule had been applied to women, as nuns, whose patroness was deemed St. Scholastica, sister of St. Benedict.

By the time of Charlemagne at the beginning of the 9th century, the Benedictine Rule had supplanted most other observances in northern and western Europe. During the five centuries following the death of Benedict, the monasteries multiplied both in size and in wealth. They were the chief repositories of learning and literature in western Europe and were also the principal educators. One of the most celebrated of Benedictine monasteries was the Burgundian Abbey of Cluny, founded as a reform house by William of Aquitaine in 910. The Cluniac reform was often imitated by other monasteries, and a succession of able abbots gradually built up throughout western Europe a great network of monasteries that followed the strict Cluniac customs and were under the direct jurisdiction of Cluny.

The great age of Benedictine predominance ended about the middle of the 12th century, and the history of the main line of Benedictine monasticism for the next three centuries was to be one of decline and decadence.

The 15th century saw the rise of a new Benedictine institution, the congregation. In 1424 the congregation of Santa Giustina of Padua instituted reforms that breathed new life into Benedictine monasticism. Superiors were elected for three years. Monks no longer took vows to a particular house but to the congregation. Further, ruling authority was concentrated in the annual general chapter or legislative meeting. This radical reform spread within a century to all the Benedictines of Italy and became known as the Cassinese Congregation. There were similar reforms throughout Europe. These reforms were confronted by the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Within a few years (1525–60) the monasteries and nunneries disappeared almost entirely from northern Europe and suffered greatly in France and central Europe. Benedictinism revived in France and Germany during the 17th century, however, and several congregations were founded, notably that of the male Maurists in France and the female Perpetual Adoration in Paris (1653) and Our Lady of Calvary (1617). Although the 18th century witnessed a new decline, from the middle of the 19th century Benedictine monasteries and nunneries again began to flourish. Foundations, including Solesmes, with its emphasis on the celebration of the liturgy, arose throughout Europe; monks and nuns returned to England; congregations were established in North and South America; and monasteries scattered all over the world. In the face of this revival, Pope Leo XIII desired to bring about some sort of unity among the traditionally independent Benedictines. In 1893 he created the office of abbot primate as head of the federation of autonomous congregations. This office, though unwelcomed because of the Benedictine desire for autonomy, gradually developed in influence.

Benedictines, in addition to their monastic life of contemplation and celebration of the liturgy, are engaged in various activities, including education, scholarship, and parochial and missionary work.

888888

![Benedict holding a bound bundle of sticks representing the strength of monks who live in community[33]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Saint_Andrew_and_Saint_Benedict_with_the_Archangel_Gabriel_%28left_panel%29_B35301.jpg/53px-Saint_Andrew_and_Saint_Benedict_with_the_Archangel_Gabriel_%28left_panel%29_B35301.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment