JOYCELYN ALSTON IN HER BRONX HOME / PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREA FREMIOTTI

In 1983, when she was 24 and living in Washington, D.C., Joycelyn Darby Alston got a phone call from her mother, Veray, who said she’d be coming to town for a visit. There was something she needed to tell her daughter, and it was best done in person. Veray Darby lived with her husband, Richard, in the northeast Bronx, where they had raised Joyce and her three brothers in a narrow brick house that came with an inviting bay window and a $258 monthly mortgage.

As the only daughter in the Darby household, Joyce had held her own. She volunteered for pickup football games and played center on her high school basketball team. It helped that she was taller than her brothers. At home, when their parents were at work—Veray as a schoolteacher, Richard as a youth counselor—Joyce would also cook for the boys. After high school, she moved to Washington, D.C., for college, working at IHOP to help pay her tuition. Washington was both new and familiar to Joyce; she’d been born there, and two of her mother’s sisters still lived there. In fact, on the day that her mother came to visit, Joyce was living with one of her aunts and working at a department store.

When Joyce first saw her mother and the look on her face, she worried something had happened to her father. “Is Dad sick?” she asked. No, her mother said.

“Your father is not your father,” Veray told her.

Joyce didn’t understand. Was their marriage in trouble?

“No,” Veray said. Richard knew why his wife had made this trip. In fact, he had given it his blessing.

Joyce’s biological father, Veray explained, was someone else. She mentioned the man’s name, but it meant nothing to Joyce. “You could not sit there and tell me that Dad is not my dad,” she recalls today, from the kitchen table in the same Bronx home where she grew up and where she now lives, once again, with her mother, who’s 89.

To Joyce, her parents’ life together had—up until that day in 1983 when her mother visited her—seemed as conventional as any other couple’s in their working-class neighborhood. Richard doted on his only daughter, and encouraged his sons to keep a close eye on any boy who dared to date Joyce. When money was tight, Richard took on weekend work selling door-to-door. Indeed, it was while he was a Fuller Brush traveling salesman that he’d first met Veray back in the late 1950s. This was in Atlanta, where Veray had grown up, attending the Allen Temple A.M.E. Church in Summerhill. Richard Darby eventually proposed to Veray, marrying her in 1959, and the young couple settled down in Washington before ultimately moving to the Bronx.

But now the identity that had defined Joyce’s life—as the only daughter of Veray and Richard Darby—was crumbling.

“I was angry,” Joyce recalls. “I was bitter. Yeah. It was almost like, ‘You’re hurting Dad, you’re not hurting me. I’m not getting any benefit out of this. So why are you doing this to him?’” Her mother had wept. “Why now?” Joyce asked.

“It’s time,” Veray replied. “I’m tired of carrying this burden.” The burden would now be Joyce’s. “Okay,” Joyce said. “Then who the hell is Herman Russell?”

By any measure, the life of Herman J. Russell was astounding. Born into poverty, the youngest of eight children, he was an entrepreneurial prodigy. At eight, he had his own paper route. At 11, he joined his father on job sites, where Rogers Russell was a master plasterer. Young Herman mixed sand and cement to make mortar. At 12, he opened a shoeshine stand across the street from his childhood home at 776 Martin Street in Summerhill. (The stand was on city-owned land, and when the racist aldermen laughed the young man with the speech impediment out of City Hall after he asked permission to do business on the parcel, Russell opened the stand anyway.) Within a month, he was subcontracting—hiring a friend to also shine shoes, and taking a nickel off the top, half the amount Russell charged his customers. On a typical day, Russell would go home with $10 in his pocket, more than the average wage of the adults around him. And he took to heart his father’s advice: “Son, if you don’t make but 50 cents, save a portion of it.”

“An ugly fiction in the South was that black folks were lazy, that black folks didn’t want to work,” Russell wrote in his autobiography, Building Atlanta, which was published in 2014, the year he died. “I can’t imagine where that came from, because all we did was work, from can’t-see-in-the-morning until can’t-see-at-night, as the saying goes. The willingness to work, to be responsible for yourself as long as your body and mind were sound enough, was an important element of self-respect for black people.”

When Herman was 14, his father bought him his own set of tools, envisioning his son would follow in his footsteps. Rogers Russell was correct, but it’s doubtful that even he would have imagined how far his youngest child would go. At 16, with money he’d saved from the shoeshine stand and from helping his father, Herman paid $125 in cash for a vacant lot in Summerhill. With help from friends, and working on it in his spare time from school, Russell built a duplex on the parcel, using his savings to pay for the raw material. One day, a year after the house was complete, a stranger approached Russell to inform him that the young man had accidentally built the house on his property, and not on Russell’s, which was actually next door. The stranger laid out the paperwork to prove his case. Russell was mortified. At a loss, he suggested to the man that they simply switch lots. To Russell’s relief, the man agreed.

“I had not paid attention to important details,” Russell wrote. “I vowed that would never happen again.”

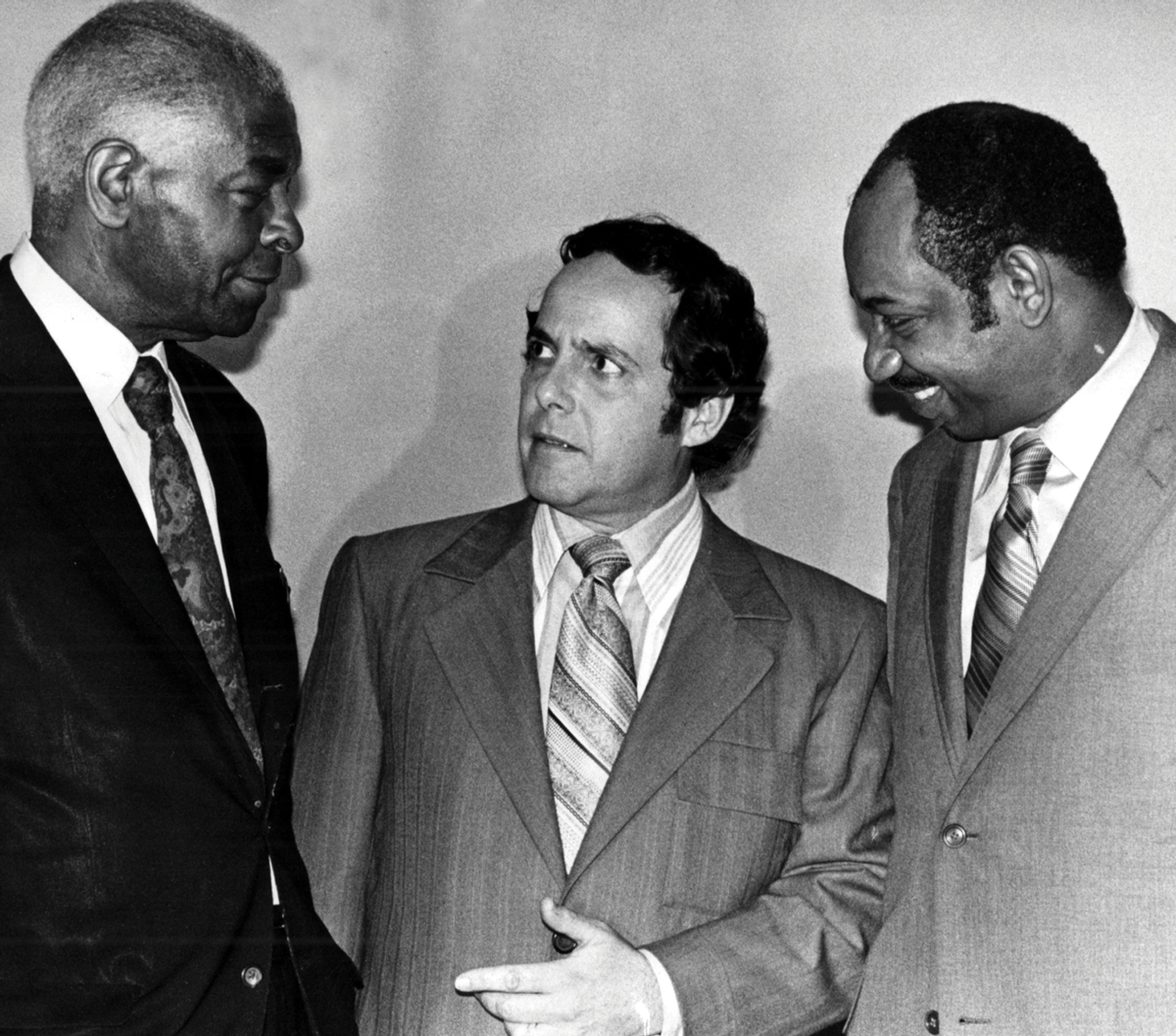

LANNA SWINDLER/AP

When he was 28, Herman Russell’s mother, Maggie, died. His father followed soon after. Rogers Russell’s thrift was borne out by his estate, which contained $12,000 in savings, an astounding amount then for a blue-collar worker with eight children. His will provided for only some of his children, since he’d written it in 1920, before his younger children, including Herman, were born. If Herman Russell felt any offense at his father’s oversight, he made no mention of it in his autobiography.

By then he likely didn’t need his father’s money anyway; six years earlier, his father had turned over his plastering business to Herman, who’d set to work immediately expanding it. H.J. Russell Plastering Company did work for general contractors across Atlanta, while also buying and building more rental units. The company grew so fast that Russell built his own headquarters in Castleberry Hill, complete with a gas pump out front for the company’s fleet of vehicles. In 1956, after a three-year courtship, Herman married Otelia Hackney, who’d grown up in Taliaferro County, midway between Atlanta and Augusta. Like Herman, Otelia was one of eight children. And like Herman, she was also strong-willed. When her friends suggested that Herman’s stammer should rule him out as a husband, Otelia was undeterred. “As long as I can understand him,” she replied, “don’t you worry about it.”

Russell used his speech impediment to his advantage, recalls Ambassador Andrew Young, who first met the builder not long after moving to Atlanta in 1961. “It made you reach out to him,” Young says. “It was almost like it was so hard for him to talk sometimes that you wanted to help him talk. What most people thought was a negative he turned into a positive.”

In 1959, the same year as his mother’s death, Herman and Otelia Russell welcomed their first child, Donata. Two boys—Jerome and Michael—followed. But it wasn’t until 2015 that the three siblings would learn they had another sister, older than all of them.

After Veray Darby told Joyce about her biological father, Joyce spoke with no one about it, except for a cousin. She didn’t tell her brothers. She didn’t discuss it further with her mother. She never mentioned it to Richard Darby, the man who raised her and whom she still saw as her father. She didn’t bring it up, nor did he. (In 1991, Richard Darby died of an aneurysm.) She never even told the man she’d marry.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREA FREMIOTTI

But at some point—Joyce estimates it was within a year of hearing the news in 1983—she wrote Herman Russell a letter. She was not sure what to say, and recalls discarding draft after draft. She settled finally on something brief—her name, her mother’s maiden name (Campbell), her aunts’ names, where the Campbell girls had grown up in Summerhill. Veray, a year older than Herman, was raised just a few blocks from the Rogers Russell house on Martin Street. The Campbell family and the Russell family also attended the same church, Allen Temple A.M.E. In the letter, Joyce remembers writing, “If you want to reach out to me, here’s my number.” She addressed the letter to the H.J. Russell Company in Atlanta and dropped it in the mail. She says she knew practically nothing about Russell or of his ever-growing stature.

What was she hoping for? “Just to get to know who [Russell] was,” she says. “‘Who are you? What do you look like? What do you do? What’s your favorite color? Who are you as a human being?’ And probably also, ‘Why?’ No matter what age you are—you could be 10, you could be 80—that information still stings.”

We live now in an age of websites that can populate your family tree going back generations. DNA tests can not only trace your lineage, but can predict with remarkable accuracy traits as banal as whether you’ll like the taste of cilantro, or whether your index finger is longer than your ring finger. All of these developments are in service to a fundamental human need—the need for connection, to know where you’re from. But 35 years ago, the best option Joyce had was the mail. She waited for a response. It never came. She sent a second letter. Again, nothing.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NOEL DAVIS/AP

At the time she sent the letters, in the mid-1980s, Herman Russell had become one of the most prominent black businessmen in the nation, overseeing a vast empire of real estate and construction interests, as well as airport concessions. On its way to becoming the largest Minority Business Enterprise real estate firm in the country, the Russell company amassed vast holdings, much of it Section 8 housing that the company would not only build but manage. In the 1960s, Russell had used his growing fortune to help fund the civil rights movement, bailing protesters out of jail. The Russell home on Shorter Terrace became a retreat for the leaders of the movement; Young and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would occasionally stop by for a swim in Russell’s pool.

Russell was a tireless networker and political kingmaker, helping persuade Young to run for Congress in 1970. “Herman integrated my life in Atlanta,” Young says. “I had been almost totally aligned with the civil rights movement, and so all that the white community saw of me were stories in the papers from Birmingham, Selma, or someplace. They had no way of knowing me personally. Herman called me up one day and said, ‘I want you to come with me,’ and he took me to meet John Portman and Charlie Loudermilk. And they became my friends and supporters.”

Russell himself became an Atlanta icon. He helped bail out Grady Hospital. He contributed toward a fund that ensured that a trove of King’s private papers would stay in Atlanta and not be auctioned off. He established his own foundation. He became an informal adviser to politicians. He grew wealthy in ways he likely had never dreamed.

After her letters to Herman Russell went unacknowledged, Joyce went on with her life. She married in 1984, taking her husband’s name—Alston. They had their son, Antonio, in 1986. Joyce’s husband was an Army doctor, so the young family’s life together was spent on the move: Seattle, South Korea, Boston. In 1999, she and her husband divorced. She had managed to push the story of her biological father from her mind, but still, she says, “it always sticks with you.” Today, she describes the unanswered questions about her lineage as an “open wound.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREA FREMIOTTI

“I could tell myself, ‘I’ll just keep living a good life,’ but that wound was always opening,” she says. “It never healed correctly. And when a wound doesn’t heal correctly, it leaves a scar.”

About five years ago, Veray Darby fell ill—so ill she was in intensive care. With her mother’s survival by no means assured, Joyce, who describes herself as very religious, began making promises to God. One of them was that if her mother survived, Joyce would try again to reach out to her biological father. By this point, Joyce’s curiosity was more than just academic; half her medical history, she realized, was unknown. Likewise, a quarter of her son’s medical history was a blank slate.

“I could tell myself, ‘I’ll just keep living a good life,’ but that wound was always opening.”

“I had a family line that I wanted to know,” she says. With Antonio now a young man, she felt it was important for him to know, too.

She called her cousin in Atlanta to discuss how to reach out, once again, to Russell. But she was too late. On November 15, 2014, Herman Russell had died.

“I beat myself up,” Joyce says. “I just missed him.” The questions she had imagined for so many years asking him—simple things such as his favorite food, or if he got into trouble as a kid—she could never ask.

Joyce had a choice: She could resume her life, or press on. Russell’s three children were very much alive. These were her siblings. Even though Russell himself was gone, perhaps she could come to know him a bit through them. “Whether they would receive me or not, I didn’t know,” she says. “But I wanted to meet them.”

In April 2015, Joyce retained the Atlanta fiduciary law firm of Gaslowitz Frankel to reach out to the Russells on her behalf. It made sense to her; after all, writing letters had yielded nothing. For her attorneys, the first priority was examining the plausibility of Joyce’s claim. Could she really be a daughter of Herman Russell? They interviewed her, her mother, and other relatives. The following narrative emerged:

In early 1958, Herman’s mother and Veray’s aunt were each ill and being treated at Grady Hospital. After her shift at the beauty parlor one day, Veray, then 28 and single, went to visit her aunt at Grady. At the hospital, she ran into Herman, a neighbor and friend she’d known since childhood. He offered her a ride home. One thing led to another.

Soon after realizing she was pregnant, Veray went to inform Russell. They agreed to meet at a bus stop. “We had a brief conversation about the pregnancy,” Veray Darby says, though she cannot recall the details of it. She does remember that before the two parted ways, Russell gave her a $50 bill. Not long after, Veray moved to Washington, D.C., where her sisters lived and where she reconnected with Richard Darby, whom she married after Joyce was born in December 1958. Although she visited Atlanta often in the ensuing years, Veray never again called the city home. She didn’t seek child support from Russell. During visits to Atlanta, she recalls, she would occasionally see Russell at church, but the two didn’t talk. At some point after Joyce’s birth, Veray says, she wrote Russell a letter. But, as with her daughter’s attempts years later, Veray never heard back.

In the summer of 2015, Joyce’s lawyers reached out to attorneys for the Russell siblings, informing them that their client claimed to be a child of Herman Russell. Not surprisingly, the Russells demanded a DNA test. For Joyce, the negotiations over the DNA test—who would pay, that the results must remain confidential, that her mother would also have to submit a sample—left her feeling marginalized, further distanced from the siblings she had yet to meet. Until then, Joyce had intentionally not researched much about the life of her biological father. Yes, she knew he was successful, but the way that the process was unfolding between lawyers on both sides led her to conclude that Herman Russell had not just been well-off, but wealthy. “I thought, ‘Am I entitled to something?’” she recalls.

In April 2016, the results came back, showing with 99.98 percent certainty that Joyce is Herman Russell’s daughter.

“In a case like this, most of the time, the critical issue is whether or not there is paternity,” says Craig Frankel, Joyce’s attorney. “Once you’ve established that there is a biological connection, the next issue is what share do you get?”

The question may seem straightforward, but as Joyce would find, nothing complicates family matters more than money.

In the fall of 2016, two years after Herman Russell’s death, Joyce traveled to Atlanta to meet the three siblings she’d never known. Half-siblings, technically, but as Joyce explains it, the family in which she had grown up made no such distinctions. You either were family, or you weren’t. And the Russells—Donata, Jerome, and Michael—were, indisputably.

“Two sisters, born just months apart almost 60 years earlier, were face to face for the first time.”

Confidentiality had been central to the discussions to this point. According to terms agreed to by both sides, Joyce and the Russells could discuss the matter with no one but each other.

“If they’re truly Herman Russell’s kids,” Veray had told her daughter before Joyce left for Atlanta, “they will receive you with open arms and love you.” At the hotel lounge where they had planned to meet, Joyce wasn’t sure whom to look for, but then a woman approached and said, “Are you Joycelyn?” It was Donata. They shook hands and sat down. Two sisters, born just months apart almost 60 years earlier, were face to face for the first time. Soon Michael arrived, and he immediately hugged Joyce. (Jerome was out of town.)

“We laughed, we talked about our kids, our careers,” Joyce says. “They told me a little about Herman Russell, what kind of father he was. We must have sat in that bar for two hours. We had a good time.” Joyce and Donata discussed their shared love of wine, and afterward, when Joyce went to walk back to her hotel, Donata insisted on giving her a ride.

Later, Joyce called her mother to tell her how it went. “She cried,” Joyce says. “She was so overjoyed. She was so thankful. She just kept saying, ‘Thank you, Lord Jesus.’”

In their only public comments on the matter, to the Atlanta Business Chronicle last September, the Russell siblings said they were curious to meet Joyce. “We were open to getting to know her,” Michael Russell said. Through a spokesman, the family declined to comment for this story.

For one of Atlanta’s wealthiest entrepreneurs, Herman Russell kept his will short—just seven pages. There were no specific dollar amounts left to friends or family members, no special bequests of sentimental items. He requested to be buried next to Otelia, who had predeceased him in 2006. (In the years after Otelia’s death, he married Sylvia Anderson, then the president of AT&T Georgia.) Beyond naming his executors, Russell did just two things in his will. First, he defined his descendants, specifying that “my only children” were Donata, Michael, and Jerome. Second, he gave “all of the residue and remainder of my estate” to a trust he’d established before his death.

Every deceased person’s assets are divided into two categories—probate and nonprobate. Items owned solely by the decedent—a car, say, or the cash in an individual bank account—go through probate, the disposition of which is overseen by probate court, according to the wishes outlined in the will. But a vast catalog of holdings bypasses probate. These items—called nonprobate assets—include life insurance proceeds, retirement accounts, jointly-held real estate. They also include trusts.

As Frankel would find out, Russell had left “precious few assets” in his probate estate. The “lion’s share,” as he put it in court documents, were nonprobate assets, some of which Russell had transferred to his three children during his lifetime. A fundamental question now was whether Joyce Alston, a biological child, was entitled to a share of these assets. Georgia law is unclear, Frankel says. The advent of DNA testing may have removed any uncertainty when it comes to blood kinship, but the emotional, financial, and legal implications are as murky as ever.

The Georgia Supreme Court has weighed in—at least partially. In 2006, a Hall County native named John Buffington died at 64. Buffington had owned a large farm and had also built up a highway construction company. In his will, he provided for his two daughters and requested that anything left over in his estate pour over to a family trust, the trustees of which were his daughters. Buffington defined his children in the will very specifically—as “only the lawful blood descendants.” A woman named Regina Todd sued in probate court, arguing she deserved a portion of Buffington’s estate. Todd claimed to be Buffington’s biological daughter, the child of an extramarital affair. But in 2010, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled against Todd, pointing in part to Buffington’s use of the word “lawful” in his will. It was “clearly and unambiguously” Buffington’s intent to provide only for his two daughters and not his out-of-wedlock child, the court ruled. In other words, you don’t need to name someone to disinherit them. But two justices dissented, with one, the late Harris Hines, calling the majority ruling a “giant step backwards in the development of the law in regard to the rights of biological children born without the benefit of marriage.”

Buffington had been aware of Todd’s existence, according to the court; he’d named her the beneficiary of two life insurance policies, and was even known to refer to her as “little bastard.” Buffington’s knowledge of Todd, and his deliberate omission of her in his will, was evidence of his intent, the court ruled. But what would have happened if he’d never known about her?

Joyce and the Russell siblings were getting to know each other. On a second trip to Atlanta, Joyce brought 32-year-old Antonio, to whom she’d recently broken the news. “Honestly,” Antonio recalls now, running his hand up his forehead, “the first thing that stuck out to me was, that explains my hairline versus Granddad’s, because his hair was so beautiful. I always wondered what happened to me.”

ELISSA EUBANKS/AP

But as the conversations—between the family members, as well as between the lawyers—turned to money, the good feelings were dissipating. As part of the confidential negotiations, Frankel got to review Herman Russell’s Form 706, an IRS filing that outlined the value of his estate. Frankel also saw details of Russell’s life insurance policies, as well as the details of trusts he established in 1993 and in 2013. Indeed, it is the trusts—and not his will—where the details of his ultimate wishes are unspooled.

As it turned out, Russell had transferred most of his fortune during his lifetime, through a series of complex transactions, to his three children, as Frankel explained at a hearing last July before Fulton County Superior Court Judge Eric Dunaway. Among the transfers of assets that occurred while Russell was alive, Frankel explained in court, were the following:

- In 1983, Russell put life insurance policies totaling approximately $5 million into a trust, the beneficiaries of which were his three children.

- In 1993, he transferred $5 million in assets—including many real estate properties—to trusts in his children’s names. Technically speaking, he sold these assets, but the income generated by them—such as rent in Section 8 housing—often exceeded the amount the children needed to pay their father back, Frankel explained.

- In 2013, Russell transferred majority ownership in his flagship company, as well as Concessions International, to trusts for each of his children, which he funded initially with $2.7 million—or $900,000 for each child, according to Frankel. In exchange, the children issued promissory notes that required no payment until 2020. If Russell died in the interim, the notes would be forgiven. The total value of the assets was roughly $28 million, although Frankel said in court he suspects the true value was closer to $50 million. “In any event,” Frankel told Judge Dunaway, “Mr. Russell did die within that seven-year period and effectively $28 million passed to his three known children at no tax.”

In court the same day, Luke Lantta, an attorney representing the Russell siblings, said Frankel made it sound like the assets were handed over freely as if they were a child’s allowance. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he said. “Each of the three Russell children had to earn what they received—working, learning the business, and earning their parents’ trust so they could ultimately be entrusted with these assets.” Nevertheless, Lantta said, more than 30 years later, someone else is coming in and trying to claim pieces of what their generation helped build.

“What would that say about his legacy? What does it say about him if he knew all these years that I existed?”

Notwithstanding the transfers Russell made to his three children during his lifetime, which totaled at least $38 million and which were all perfectly allowable under the law, he did not die a pauper. As Frankel explained in court, Russell left $10 million to his second wife. The “residue and remainder” of his estate that he cited in his will included a Midtown condominium, a vacation home on Lake Burton, as well as personal property. All of it went into yet another trust.

Frankel says Russell’s intentions, through estate planning done over decades, were clear: “To give his property, with minimal taxes, to his children.” Frankel estimates that the true value of Russell’s estate was north of $100 million, and could be as high as $200 million.

This is a good time to note that Joycelyn Alston works as an accountant. As a clearer picture of her birth father’s fortune began to emerge, it put into context the settlement offer she got from the Russells in the first days of 2017. The offer was $450,000, to be paid over two years, as well as her choice between a 10 percent interest in the Lake Burton vacation home or $500,000 paid over 10 years into a trust for her and her “lineal descendants,” with Joyce naming the trustee and the trustee paying the taxes. And the settlement was to remain confidential. To Joyce, it was insufficient.

“Just be fair, that’s all I’m saying,” Joyce says, explaining her expectations. “And when I say ‘Be fair,’ I’m not asking for a suitcase full of money. There’s other things. There’s things that can be set up for [Antonio], for my grandkids. There’s education, sitting on the board.” (Jerome Russell is president and executive director of the Herman J. Russell Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, which in 2016 reported $4.9 million in net assets.)

Joyce had imagined being introduced to the extended family, to assimilating, to having a seat at the table, figuratively and otherwise. But, as Frankel explains it, the Russells wanted to keep her existence private. Joyce began to take offense. A phone call she had with her newfound siblings, discussing a possible settlement, didn’t help. No disrespect, Joyce, she recalls one of them saying, but you didn’t earn it.

Joyce says she responded, “I paid my way through college, I raised my son, I’ve done well for myself, I have a good job, I’m well-educated, so I did earn it.”

Joyce is also motivated in part by the thought of her mother, who had never sought any money from Russell. Here was a way to make things right. “Give my mama some back child support—that’s my attitude,” Joyce says.

On the morning of January 9, 2017, Joyce sued the Estate of Herman Russell in Fulton Superior Court, seeking to be declared an heir and asking the court to effectively award her a share of Russell’s nonprobate assets equal to what he gave his three other children. That afternoon, Donata, as co-executor of her father’s estate, sued Joyce in Fulton County Probate Court. The suit acknowledged Joyce was Herman’s biological daughter but requested that the court exclude her from any share of Russell’s estate.

The matter that had been strictly hush-hush had become public record. (Well, not entirely public. Lawyers for the Russell siblings have persuaded the respective judges in both of those courtrooms—Judge Pinkie Toomer in Fulton County Probate Court and Dunaway in Fulton Superior Court—to keep swaths of the cases out of the public eye, effectively turning what are supposed to be open proceedings into closed ones.)

And, with the filing of the lawsuits, communications between Joyce and the Russell siblings ended.

Did Herman Russell know he had fathered a child out of wedlock? In the interview last September with the Atlanta Business Chronicle, the three Russell siblings said they simply didn’t know if their father knew about Joyce. However, their suit against Joyce in probate court asserted that Herman Russell “was aware that he may have biological children” other than Donata, Jerome, and Michael, and that he “chose not to provide for those potential other children in his estate planning documents.” The suit went on to state that when he executed his final will, their father was “aware that Ms. Alston claimed to be his biological child, and he chose not to provide for her in his estate planning documents.”

If the Russell siblings can demonstrate that their father knew about Joyce—after all, both Veray and Joyce said they wrote him letters over the years, though neither ever got a response—then the details would be similar to the Buffington case, and it’s likely Joyce’s case would fail in superior court.

But for the Russells, winning in court could come with unintended consequences. If he’d knowingly fathered a child and didn’t provide for her, the reputation he spent a lifetime building could be called into question. “What would that say about his legacy?” Joyce says. “What does it say about him if he knew all these years that I existed?”

Young, who’s not followed the case closely, says it is incomprehensible that Russell would knowingly turn his back on his own child. “He would never have neglected a child of his,” Young says. “If he had been aware of her, she’d at least have a trust fund and be guaranteed an education. He would never let a child of his not be part of his family.”

Assuming the parties can’t come to a settlement, Frankel believes the court’s ultimate decision will come to be known as the “Russell Doctrine”—whether an unknown heir is entitled to a portion of their deceased parent’s nonprobate estate. Joyce is less interested in making history. She wants what she believes is fair—and still hopes to get to know better the siblings with whom she was only starting to get acquainted.

“It had to be crazy for them,” Joyce says. “I have my own emotions about this, but I’m sure they have theirs, too. It’s like I told my son, I feel like we—me and the Russells—are like the clean-ups; we’re just cleaning up some mess that our parents made. We’re left to do it.”

POSTSCRIPT

On January 9, a week after this story had gone to press for our February 2019 issue, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Eric Dunaway dismissed Joycelyn Alston’s verified petition seeking heirship. He also dismissed Alston’s amended complaint that sought a share of Herman Russell’s estate. Dunaway cited many arguments in making his ruling, including that Georgia law prohibits a claim such as hers, and that the statute of limitations had run out. Dunaway ruled that because Alston is neither a “trustee nor a beneficiary,” she is not entitled to ask that the trusts that Herman Russell set up be terminated. (Read the entire 39-page ruling here.)

Luke Lantta, attorney for the Russell estate, said, “We are pleased that the court reached what we think is the right decision and one that allows everyone to move forward.”

But Craig Frankel, Alston’s attorney, said the legal battle isn’t over yet, and that his client would take her case to the Georgia Court of Appeals.

“I’m disappointed but not surprised that the judge took the safe way out,” Frankel said. “This is a new area of law and [Judge Dunaway] is going to let the appellate courts decide. It’d be a shame if the Georgia courts hold that a biological child of a man who is wealthy has no rights simply because the father had enough money to do estate planning outside of probate.”

The probate case, concerning assets that Russell had outlined in his will, is still pending in Fulton County probate court.

This article appears in our February 2019 issue.