Kenny Rogers obituary

One of the great American country singers who had hits with The Gambler, Lucille and Islands in the Stream

Kenny Rogers, who has died aged 81, was a prolific hit-maker from the late 1960s into the 80s, and with songs such as Lucille, The Gambler and Coward of the County helped to create a bestselling crossover of pop and country material. “I did songs that were not country but were more pop,” he said in 2016. “If the country audience doesn’t buy it, they’ll kick it out. And if they do, then it becomes country music.”

Rogers’s knack for finding a popular song – he was modest about his own writing skills and preferred to pick songs from other writers – was unerring, bringing him huge hits with Don Schlitz’s The Gambler (1978), Lionel Richie’s Lady (1980), and, with Dolly Parton, the Bee Gees’ Islands in the Stream (1983) among many others. Though his record sales waned in the late 80s, he bounced back in his last years with three successful albums, The Love of God (2011), You Can’t Make Old Friends (2013) and Once Again It’s Christmas (2015). Altogether he recorded 65 albums and sold more than 165m records.

Born in Houston, Texas, Kenny was the fourth of eight children of Lucille (nee Hester), a nursing assistant, and Edward Rogers, a carpenter, and grew up in the San Felipe Courts housing project. He attended Jefferson Davis high school, where he formed his first band, a doo-wop group called the Scholars, in which he sang and played guitar.

In 1956 he left school and within two years had scored a solo hit with That Crazy Feeling, which earned him an appearance on the TV show American Bandstand. He then played bass in the jazz trio the Bobby Doyle Three before moving to Los Angeles and joining the folk group the New Christy Minstrels.

In 1967 Rogers formed the First Edition (which also included New Christy Minstrels songwriter Mike Settle), and they proceeded to notch up seven Top 40 pop hits, including Mickey Newbury’s Just Dropped in to See What Condition My Condition Was In (1967, and later used for a memorable dream sequence in the 1998 film The Big Lebowski). Their most prominent hit was their version of Mel Tillis’s Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town, written from the viewpoint of a paralysed Vietnam veteran. Featuring the pained, sandpapery vocal delivery that would become Rogers’s trademark, in 1969 it reached No 2 in the UK and 6 on the Billboard pop chart.

The First Edition also made a couple of movie appearances, and in 1971 began hosting their own TV show, Rollin’ on the River. But by 1975 the group were in commercial decline, prompting Rogers to start a solo career with the United Artists label.

In 1977 he topped the US country chart for the first time with Lucille (also a No 1 hit in the UK and several other countries), another storytelling song, which sold 5m copies worldwide. It paved the way for further Rogers classics including The Gambler (1978, another Country No 1 and a US Top 20 pop hit) and Coward of the County (1979, a UK and Country No 1, and a No 3 on the US pop chart).

Rogers’s yearning vocal tone also made him a natural ballad singer, as he demonstrated with the chart-topping Lady. Another of his talents was picking the right duet partners. He teamed up with Dottie West on a string of big country hits in the late 70s and early 80s, including three No 1s, and reached the US Top 5 with Kim Carnes on Don’t Fall in Love With a Dreamer (1980). That track came from a chart-topping concept album that Carnes and her husband, Dave Ellingson, wrote for Rogers, called Gideon, the story of cowboy Gideon Tanner.

His collaboration with Sheena Easton on We’ve Got Tonight (1983) was a Country No 1 and reached No 6 on the pop chart. In the same year he achieved one of his best-loved career highlights by duetting with Parton on Islands in The Stream, an international smash. “Everybody always thought we were having an affair,” Rogers said of his great friend Parton. “We didn’t. We just teased each other and flirted with each other for 30 years.”

In 1985 he was one of the featured superstars on USA for Africa’s We Are the World. His album The Heart of the Matter of the same year, produced by George Martin, was his last to top the US Country chart, and the following year he was voted favourite singer of all time by USA Today and People magazine. He won a Grammy award for Make No Mistake, She’s Mine (1987), a duet with Ronnie Milsap that was his penultimate Country No 1 single.

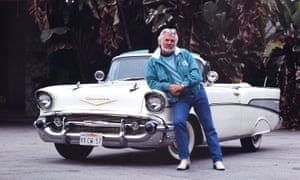

But Rogers had several strings to his bow. His hit The Gambler had spawned a string of TV films in which he played the title role of Brady Hawkes. In 1991, with former Kentucky Fried Chicken chief executive John Y Brown Jr, he launched a string of chicken restaurants called Kenny Rogers Roasters. Having starred as a racing car driver in the movie Six Pack (1982), Rogers collaborated with Sprint car driver CK Spurlock to create the car manufacturer Gambler Chassis.

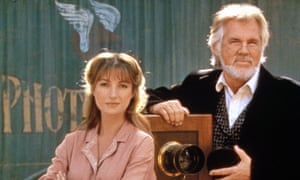

A keen amateur photographer, Rogers was spurred to develop his skills further when he married his fourth wife, Marianne Gordon, a model. As well as taking portraits of her, Rogers studied with the photographers John Sexton and Yousuf Karsh. In 1986 he published Kenny Rogers’ America, featuring images taken while on tour, while Your Friends and Mine (1987) comprised portraits of superstars including Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Jackson. Country music stars including Willie Nelson, Tammy Wynette and Parton were the subjects of This Is My Country (2005).

He was also an author. The book of his touring musical play The Toy Shoppe was published in 2000, his memoir, Luck Or Something Like It, appeared in 2012, and the following year brought his novel (co-written with Mike Blakely), What Are the Chances.

Among his countless honours were three Grammys, six Country Music Association awards and eight Academy of Country Music awards, and in 2013 he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Having delivered a rousing performance in the Sunday afternoon “Legends” slot at the Glastonbury festival in 2013, Rogers embarked on his farewell tour, The Gambler’s Last Deal, in 2016. On 25 October 2017, he was given an all-star send-off at Nashville’s Bridgestone arena by guests including Richie, Parton, Don Henley, Kris Kristofferson and Reba McEntire.

Kenny was wed five times. The first four marriages, to Janice (nee Gordon), Jean Rogers, Margo (nee Anderson), and Marianne, ended in divorce. He is survived by his fifth wife, Wanda (nee Miller), their twin sons, Justin and Jordan, a daughter, Carole, from his marriage to Janice, a son, Kenny Jr, from his marriage to Margo, and another son, Christopher, from his marriage to Marianne.

•Kenny (Kenneth Ray) Rogers, singer and musician, born 21 August 1938; died 20 March 2020