Martin Luther King Jr.: Leader of Millions in Nonviolent Drive for Racial JusticeBy MURRAY SCHUMACHTo many million of American Negroes, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was the prophet of their crusade for racial equality. He was their voice of anguish, their eloquence in humiliation, their battle cry for human dignity. He forged for them the weapons of nonviolence that withstood and blunted the ferocity of segregation.And to many millions of American whites, he was one of a group of Negroes who preserved the bridge of communication between races when racial warfare threatened the United States in the nineteen-sixties, as Negroes sought the full emancipation pledged to them a century before by Abraham Lincoln. To the world Dr. King had the stature that accrued to a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, a man with access to the White House and the Vatican; a veritable hero in the African states that were just emerging from colonialism. Between Extremes In his dedication to non-violence, Dr. King was caught between white and Negro extremists as racial tensions erupted into arson, gunfire and looting in many of the nation's cities during the summer of 1967. Militant Negroes, with the cry of, "burn, baby burn," argued that only by violence and segregation could the Negro attain self-respect, dignity and real equality in the United States. Floyd B. McKissick, when director of the Congress of Racial Equality, declared in August of that year that it was a "foolish assumption to try to sell nonviolence to the ghettos." And white extremists, not bothering to make distinctions between degrees of Negro militancy, looked upon Dr. King as one of their chief enemies. At times in recent months, efforts by Dr. King to utilize nonviolent methods exploded into violence. Violence in Memphis Last week, when he led a protest march through downtown Memphis, Tenn., in support of the city's striking sanitation workers, a group of Negro youths suddenly began breaking store windows and looting, and one Negro was shot to death. Two days later, however, Dr. King said he would stage another demonstration and attributed the violence to his own "miscalculation." At the time he was assassinated in Memphis, Dr. King was involved in one of his greatest plans to dramatize the plight of the poor and stir Congress to help Negroes. He called this venture the "Poor People's Campaign." It was to be a huge "camp-in" either in Washington or in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. In one of his last public announcements before the shooting, Dr. King told an audience in a Harlem church on March 26: "We need an alternative to riots and to timid supplication. Nonviolence is our most potent weapon." His strong beliefs in civil rights and nonviolence made him one of the leading opponents of American participation in the war in Vietnam. To him the war was unjust, diverting vast sums away from programs to alleviate the condition of the Negro poor in this country. He called the conflict "one of history's most cruel and senseless wars." Last January he said: "We need to make clear in this political year, to Congressmen on both sides of the aisle and to the President of the United States that we will no longer vote for men who continue to see the killing of Vietnamese and Americans as the best way of advancing the goals of freedom and self- determination in Southeast Asia." Object of Many AttacksInevitably, as a symbol of integration, he became the object of unrelenting attacks and vilification. His home was bombed. He was spat upon and mocked. He was struck and kicked. He was stabbed, almost fatally, by a deranged Negro woman. He was frequently thrown into jail. Threats became so commonplace that his wife could ignore burning crosses on the lawn and ominous phone calls. Through it all he adhered to the creed of passive disobedience that infuriated segregationists. The adulation that was heaped upon him eventually irritated some Negroes in the civil rights movement who worked hard, but in relative obscurity. They pointed out--and Dr. King admitted--that he was a poor administrator. Sometimes, with sarcasm, they referred to him, privately, as "De Lawd." They noted that Dr. King's successes were built on the labors of may who had gone before him, the noncoms and privates of the civil rights army who fought without benefit of headlines and television cameras. The Negro extremists he criticized were contemptuous of Dr. King. They dismissed his passion for nonviolence as another form of servility to white people. They called him an "Uncle Tom," and charged that he was hindering the Negro struggle for equality. Dr. King's belief in nonviolence was subjected to intense pressure in 1966, when some Negro groups adopted the slogan "black power" in the aftermath of civil rights marches into Mississippi and race riots in Northern cities. He rejected the idea, saying: "The Negro needs the white man to free him from his fears. The white man needs the Negro to free him from his guilt. A doctrine of black supremacy is as evil as a doctrine of white supremacy." The doctrine of "black power" threatened to split the Negro civil rights movement and antagonize white liberals who had been supporting Negro causes, and Dr. King suggested "militant nonviolence" as a formula for progress with peace. At the root of his civil rights convictions was an even more profound faith in the basic goodness of man and the great potential of American democracy. These beliefs gave to his speeches a fervor that could not be stilled by criticism. Scores of millions of Americans--white was well as Negro--who sat before television sets in the summer of 1963 to watch the awesome march of some 200,000 Negroes on Washington were deeply stirred when Dr. King, in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, said: "Even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.'" And all over the world, men were moved as they read his words of Dec. 10, 1964, when he became the third member of his race to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Insistent on Man's Destiny "I refuse to accept the idea that man is mere flotsam and jetsam in the river of life which surrounds him," he said. "I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality. "I refuse to accept the cynical notion that nation after nation must spiral down a militaristic stairway into the hell of thermonuclear destruction. I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant." For the poor and unlettered of his own race, Dr. King spoke differently. There he embraced the rhythm and passion of the revivalist and evangelist. Some observers of Dr. King's technique said that others in the movement were more effective in this respect. But Dr. King had the touch, as he illustrated in a church in Albany, Ga., in 1962: "So listen to me, children: Put on your marching shoes; don'cha get weary; though the path ahead may be dark and dreary; we're walking for freedom, children." Or there was the meeting in Gadsen, Ala., late in 1963, when he displayed another side of his ability before an audience of poor Negroes. It went as follows: King: I hear they are beating you. Audience: Yes, yes. King: I hear they are cursing you. Audience: Yes, yes. King: I hear they are going into your homes and doing nasty thing and beating you. Audience: Yes, yes. King: Some of you have knives, and I ask you to put them up. Some of you have arms, and I ask you to put them up. Get the weapon of non-violence, the breastplate of righteousness, the armor of truth, and just keep marching." It was said that so devoted was his vast following that even among illiterates he could, by calm discussion of Platonic dogma, evoke deep cries of "Amen." Dr. King also had a way of reducing complex issues to terms that anyone could understand. Thus, in the summer of 1965, when there was widespread discontent among Negroes about their struggle for equality of employment, he declared: "What good does it do to be able to eat at a lunch counter if you can't buy a hamburger." The enormous impact of Dr. King's words was one of the reasons he was in the President's Room in the Capitol on Aug. 6, 1965, when President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act that struck down literacy tests, provided Federal registrars to assure the ballot to unregistered Negroes and marked the growth of the Negro as a political force in the South. Backed by Organization Dr. King's effectiveness was enhanced and given continuity by the fact that he had an organization behind him. Formed in 1960, with headquarters in Atlanta, it was called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, familiarly known as SLICK. Allied with it was another organization formed under Dr. King's sponsorship the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, often referred to as SNICK. These two organizations reached the country, though their basic strength was in the South. They brought together Negro clergymen, businessmen, professional men and students. They raised the money and planned the sit-ins, the campaigns for Negro vote registration, the demonstrations by which Negroes hacked away at segregationist resistance, lowering the barriers against Negroes in the political, economic and social life of the nation. This minister, who became the most famous spokesman for Negro rights since Booker T. Washington, was not particularly impressive in appearance. About 5 feet 8 inches tall, he had an oval face with almond-shaped eyes that looked almost dreamy when he was off the platform. His neck and shoulders where heavily muscled, but his hands were almost delicate. Speaker of Few Gestures There was little of the rabblerouser in his oratory. He was not prone to extravagant gestures or loud peroration. His baritone voice, though vibrant, was not that of a spellbinder. Occasionally, after a particular telling sentence, he would tilt his head a bit and fall silent as though waiting for the echoes of his thought to spread through the hall, church or street. In private gatherings, Dr. King lacked that laughing gregariousness that often makes for popularity. Some thought he was without a sense of humor. He was not a gifted raconteur. He did not have the flamboyance of a Representative Adam Clayton Powell Jr. or the cool strategic brilliance of Roy Wilkins, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. What Dr. King did have was an instinct for the right moment to make his moves. Some critics looked upon this as pure opportunism. Nevertheless, it was this sense of timing that raised him in 1955, from a newly arrived minister in Montgomery, Ala., with his first church, to a figure of national prominence. Bus Boycott in Progress Negroes in that city had begun a boycott of buses to win the right to sit where they pleased instead of being forced to move to the rear of buses, in Southern tradition or to surrender seats to white people when a bus was crowded. The 381-day boycott by Negroes was already under way when the young pastor was placed in charge of the campaign. It has been said that one of the reasons he got the job was because he was so new in the area he had not antagonized any of the Negro factions. Even while the boycott was under way, a board of directors handled the bulk of administrative work. However, it was Dr. King who dramatized the boycott with his decision to make it the testing ground, before the eyes of the nation, of his belief in the civil disobedience teachings of Thoreau and Gandhi. When he was arrested during the Montgomery boycott, he said: "If we are arrested every day, if we are exploited every day, if we are trampled over every day, don't ever let anyone pull you so low as to hate them. We must use the weapon of love. We must have compassion and understanding for those who hate us. We must realize so many people are taught to hate us that they are not totally responsible for their hate. But we stand in life at midnight; we are always on the threshold of a new dawn." Home Bombed in Absence Even more dramatic, in some ways, was his reaction to the bombing of his home during the boycott. He was away at the time and rushed back fearful for his wife and children. They were not injured. But when he reached the modest house, more than a thousand Negroes had already gathered and were in an ugly mood, seeking revenge against the white people. The police were jittery. Quickly, Dr. King pacified the crowd and there was no trouble. Dr. King was even more impressive during the "big push" in Birmingham, which began in April, 1963. With the minister at the limelight, Negroes there began a campaign of sit-ins at lunch counters, picketing and protest marches. Hundreds of children, used in the campaign, were jailed. The entire world was stirred when the police turned dogs on the demonstrators. Dr. King was jailed for five days. While he was in prison he issued a 9,000-word letter that created considerable controversy among white people, alienating some sympathizers who thought Dr. King was being too aggressive. Moderates Called Obstacles In the letter he wrote: "I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace, which is the absence of tension, to a positive peace, which is the presence of justice." Some critics of Dr. King said that one reason for this letter was to answer Negro intellectuals, such as the wrier James Baldwin, who were impatient with Dr. King's belief in brotherhood. Whatever the reasons, the role of Dr. King in Birmingham added to his stature and showed that his enormous following was deeply devoted to him. He demonstrated this in a threatening situation in Albany, Ga., after four Negro girls were killed in the bombing of a church. Dr. King said at the funeral: "In spite of the darkness of this hour, we must not despair. We must not lose faith in our white brothers." As Dr. King's words grew more potent and he was invited to the White House by President Kennedy and Johnson, some critics--Negroes as well as white--noted that sometimes, despite all the publicity he attracted, he left campaigns unfinished or else failed to attain his goals. Dr. King was aware of this. But he pointed out, in 1964, in St Augustine, Fla., one of the toughest civil rights battlegrounds, that there were important intangibles. "Even if we do not get all we should," he said, "movements such as this tend more and more to give a Negro the sense of self-respect that he needs. It tends to generate courage in Negroes outside the movement. It brings intangible results outside the community where it is carried out. There is a hardening of attitudes in situations like this. But other cities see and say: "We don't want to be another Albany or Birmingham,' and they make changes. Some communities, like this one, had to bear the cross." It was in this city that Negroes marched into the fists of the mob singing: "We love everybody." Conscious of Leading Role There was no false modesty in Dr. King's self appraisal of his role in the civil rights movement. "History," he said, "has thrust me into this position. It would be both immoral and a sign of ingratitude if I did not face my moral responsibility to do what I can in this struggle." Another time he compared himself to Socrates as one of "the creative gadflies of society." At times he addressed himself deliberately to the white people of the nations. Once, he said: "We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you, but we cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws. . .We will soon were you down by our capacity to suffer. And in winning our freedom we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process." The enormous influence of Dr. King's voice in the turbulent racial conflict reached into New York in 1964. In the summer of that year racial rioting exploded in New York and in other Northern cities with large Negro populations. There was widespread fear that the disorders, particularly in Harlem, might set of unprecedented racial violence. At this point Dr. King became one of the major intermediaries in restoring order. He conferred with Mayor Robert F. Wagner and with Negro leaders. A statement was issued, of which he was one of the signers, calling for "a broad curtailment if not total moratorium on mass demonstrations until after Presidential elections." The following year, Dr. King was once more in the headlines and on television--this time leading a drive for Negro voter registration in Selma, Ala. Negroes were arrested by the hundreds. Dr. King was punched and kicked by a white man when, during this period of protest, he became the first Negro to register at a century-old hotel in Selma. Martin Luther King Jr. was born Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta on Auburn Avenue. As a child his name was Michael Luther King and so was his father's. His father changed both their names legally to Martin Luther King in honor of the Protestant reformer. Auburn Avenue is one of the nation's most widely known Negro sections. Many successful Negro business or professional men have lived there. The Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. was pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church at Jackson Street and Auburn Avenue. Young Martin went to Atlanta's Morehouse College, a Negro institution whose students acquired what was sometimes called the "Morehouse swank." The president of Morehouse, Dr. B. E. Mays, took a special interest in Martin, who had decided, in his junior year, to be a clergyman. He was ordained a minister in his father's church in 1947. It was in this church he was to say, some years later: "America, you're strayed away. You've trampled over 19 million of your brethren. All men are created equal. Not some men. Not white men. All men. America, rise up and come home." Before Dr. King had his own church he pursued his studies in the integrated Crozier Theological Seminary, in Chester, Pa. He was one of six Negroes in a student body of about a hundred. He became the first Negro class president. He was named the outstanding student and won a fellowship to study for a doctorate at the school of his choice. The young man enrolled at Boston College in 1951. For his doctoral thesis he sought to resolve the differences between the Harvard theologian Paul Tillich and the neo-naturalist philosopher Henry Nelson Wieman. During this period he took courses at Harvard, as well. While he was working on his doctorate he met Coretta Scott, a graduate of Antioch College, who was doing graduate work in music. He married the singer in 1953. They had four children, Yolanda, Martin Luther King 3d, Dexter Scott and Bernice. In 1954, Dr. King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala. At that time few of Montgomery's white residents saw any reason for a major dispute with the city's 50,000 Negroes. They did not seem to realize how deeply the Negroes resented segregated seating on buses, for instance. Revolt Begun by Woman On Dec. 1, 1955, they learned, almost by accident. Mrs. Rosa Parks, a Negro seamstress, refused to comply with a bus driver's order to give up her seat to a white passenger. She was tired, she said. Her feet hurt from a day of shopping. Mrs. Parks had been a local secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She was arrested, convicted of refusing to obey the bust conductor and fined $10 and cost, a total of $14. Almost as spontaneous as Mrs. Parks's act was the rallying of many Negro leaders in the city to help her. From a protest begun over a Negro woman's tired feet Dr. King began his public career. In 1959, Dr. King and his family moved back to Atlanta, where he became a co-pastor, with his father, of the Ebenezer Baptist Church. As his fame increased, public interest in his beliefs led him to write books. It was while he was autographing one of these books, "Stride Toward Freedom," in a Harlem department store that he was stabbed by a Negro woman. It was in these books that he summarized, in detail, his beliefs as well as his career. Thus, in "Why We Can't Wait," he wrote: "The Negro knows he is right. He has not organized for conquest or to gain spoils or to enslave those who have injured him. His goal is not to capture that which belongs to someone else. He merely wants, and will have, what is honorably his." The possibility that he might someday be assassinated was considered by Dr. King on June 5, 1964, when he reported, in St. Augustine, Fla., that his life had been threatened. He said: "Well, if physical death is the price that I must pay to free my white brothers and sisters from a permanent death of the spirit, then nothing can be more redemptive." | ||||||||||

____________________________________________________________________________________

Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968), was an American Baptist minister, activist, humanitarian, and leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights using nonviolent civil disobedience based on his Christian beliefs.

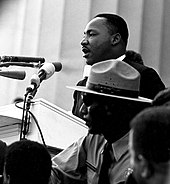

King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. With the SCLC, King led an unsuccessful 1962 struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia (the Albany Movement), and helped organize the 1963 nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, that attracted national attention following television news coverage of the brutal police response. King also helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. There, he established his reputation as one of the greatest orators in American history.

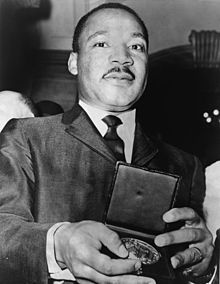

On October 14, 1964, King received the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolence. In 1965, he helped to organize the Selma to Montgomery marches, and the following year he and SCLC took the movement north to Chicago to work on segregated housing. In the final years of his life, King expanded his focus to include poverty and speak against the Vietnam War, alienating many of his liberal allies with a 1967 speech titled "Beyond Vietnam".

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971, and as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and a county in Washington State was also renamed for him. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

Contents[hide]

Early life and education

King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr., and Alberta Williams King.[1] King's legal name at birth was Michael King,[2] and his father was also born Michael King, but the elder King changed his and his son's names following a 1934 trip to Germany to attend the Fifth Baptist World Alliance Congressin Berlin. It was during this time he chose to be called Martin Luther King in honor of the German reformer Martin Luther.[3][4] King had Irish ancestry through his paternal great-grandfather.[5][6]

Martin, Jr., was a middle child, between an older sister, Willie Christine King, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel Williams King.[7] King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind.[8] King liked singing and music. King's mother, an accomplished organist and choir leader, took him to various churches to sing. He received attention for singing "I Want to Be More and More Like Jesus." King later became a member of the junior choir in his church.[9]

King said his father regularly whipped him until he was fifteen and a neighbor reported hearing the elder King telling his son "he would make something of him even if he had to beat him to death." King saw his father's proud and unafraid protests in relation to segregation, such as Martin, Sr., refusing to listen to a traffic policeman after being referred to as "boy" or stalking out of a store with his son when being told by a shoe clerk that they would have to move to the rear to be served.[10]

When King was a child, he befriended a white boy whose father owned a business near his family's home. When the boys were 6, they attended different schools, with King attending a segregated school for African-Americans. King then lost his friend because the child's father no longer wanted them to play together.[11]

King suffered from depression throughout much of his life. In his adolescent years, he initially felt some resentment against whites due to the "racial humiliation" that he, his family, and his neighbors often had to endure in the segregated South.[12] At age 12, shortly after his maternal grandmother died, King blamed himself and jumped out of a second story window, but survived.[13]

King was originally skeptical of many of Christianity's claims.[14] At the age of thirteen, he denied the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school. From this point, he stated, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly".[15] However, he later concluded that the Bible has "many profound truths which one cannot escape" and decided to enter the seminary.[14]

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He became known for his public speaking ability and was part of the school's debate team.[16] King became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal in 1942 at age 13.[17] During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Georgia. Returning home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so white passengers could sit down. King refused initially, but complied after his teacher informed him that he would be breaking the law if he did not go along with the order. He later characterized this incident as "the angriest I have ever been in my life".[16] A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school.[18] It was during King's junior year that Morehouse College announced it would accept any high school juniors who could pass its entrance exam. At that time, most of the students had abandoned their studies to participate inWorld War II. Due to this, the school became desperate to fill in classrooms. At age 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse.[16] The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, an eighteen-year-old King made the choice to enter the ministry after he concluded the church offered the most assuring way to answer "an inner urge to serve humanity". King's "inner urge" had begun developing and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a "rational" minister with sermons that were "a respectful force for ideas, even social protest."[19]

In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951.[20][21] King's father fully supported his decision to continue his education. King was joined in attending Crozer by Walter McCall, a former classmate at Morehouse.[22] At Crozer, King was elected president of the student body.[23]The African-American students of Crozer for the most part conducted their social activity on Edwards Street. King was endeared to the street due to a classmate having an aunt that prepared the two collard greens, which they both relished.[24] King once called out a student for keeping beer in his room because of their shared responsibility as African-Americans to bear "the burdens of the Negro race." For a time, he was interested in Walter Rauschenbusch's "social gospel".[23] In his third year there, he became romantically involved with the daughter of an immigrant German woman working as a cook in the cafeteria. The daughter had been involved with a professor prior to her relationship with King. King had plans of marrying her, but was advised not to by friends due to the reaction an interracial relationship would spark from both blacks and whites, as well as the chances of it destroying his chances of ever pastoring a church in the South. King tearfully told a friend that he could not endure his mother's pain over the marriage and broke the relationship off around six months later. He would continue to have lingering feelings, with one friend being quoted as saying, "He never recovered."[23]

King married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama.[25] They became the parents of four children: Yolanda King (b. 1955), Martin Luther King III(b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961), and Bernice King (b. 1963).[26] During their marriage, King limited Coretta's role in the Civil Rights Movement, expecting her to be a housewife and mother.[27]

Doctoral studies

King then began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Ph.D. degree on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation on "A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman". An academic inquiry concluded in October 1991 that portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly. However, "[d]espite its finding, the committee said that 'no thought should be given to the revocation of Dr. King's doctoral degree,' an action that the panel said would serve no purpose."[28][29][30] The committee also found that the dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." However, a letter is now attached to King's dissertation in the university library, noting that numerous passages were included without the appropriate quotations and citations of sources.[31]

Ideas, influences, and political stancesReligion

King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was twenty-five years old, in 1954.[32] As a Christian minister, his main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. King's faith was strongly based in Jesus' commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His nonviolent thought was also based in the injunction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus' teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52).[33] In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus' "extremist" love, and also quoted numerous otherChristian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

In his speech "I've Been to the Mountaintop", he stated that he just wanted to do God's will.

Nonviolence

Veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin was King's first regular advisor on nonviolence.[36] King was also advised by the white activists Harris Wofford andGlenn Smiley.[37] Rustin and Smiley came from the Christian pacifist tradition, and Wofford and Rustin both studied Gandhi's teachings. Rustin had applied nonviolence with theJourney of Reconciliation campaign in the 1940s,[38] and Wofford had been promoting Gandhism to Southern blacks since the early 1950s.[37] King had initially known little about Gandhi and rarely used the term "nonviolence" during his early years of activism in the early 1950s. King initially believed in and practiced self-defense, even obtaining guns in his household as a means of defense against possible attackers. The pacifists guided King by showing him the alternative of nonviolent resistance, arguing that this would be a better means to accomplish his goals of civil rights than self-defense. King then vowed to no longer personally use arms.[39][40]

In the aftermath of the boycott, King wrote Stride Toward Freedom, which included the chapter Pilgrimage to Nonviolence. King outlined his understanding of nonviolence, which seeks to win an opponent to friendship, rather than to humiliate or defeat him. The chapter draws from an address by Wofford, with Rustin and Stanley Levison also providing guidance and ghostwriting.[41]

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's success with nonviolent activism, King had "for a long time...wanted to take a trip to India".[42] With assistance from Harris Wofford, theAmerican Friends Service Committee, and other supporters, he was able to fund the journey in April 1959.[43] [44] The trip to India affected King, deepening his understanding of nonviolent resistance and his commitment to America's struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, "Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity".

Bayard Rustin's open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin,[45] which King agreed to do.[46] However, King agreed that Rustin should be one of the main organizers of the 1963 March on Washington.[47]

King's admiration of Gandhi's nonviolence did not diminish in later years. He went so far as to hold up his example when receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, hailing the "successful precedent" of using nonviolence "in a magnificent way by Mohandas K. Gandhi to challenge the might of the British Empire... He struggled only with the weapons of truth, soul force, non-injury and courage."[48]

Gandhi seemed to have influenced him with certain moral principles,[49] though Gandhi himself had been influenced by The Kingdom of God Is Within You, a nonviolent classic written by Christian anarchist Leo Tolstoy. In turn, both Gandhi and Martin Luther King had read Tolstoy, and King, Gandhi and Tolstoy had been strongly influenced by Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. King quoted Tolstoy's War and Peace in 1959.[50]

Another influence for King's nonviolent method was Henry David Thoreau's essay On Civil Disobedience, which King read in his student days. He was influenced by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system.[51] He also was greatly influenced by the works of Protestant theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich,[52] as well as Walter Rauschenbusch's Christianity and the Social Crisis. King also sometimes used the concept of "agape" (brotherly Christian love).[53] However, after 1960, he ceased employing it in his writings.[54]

Even after renouncing his personal use of guns, King had a complex relationship with the phenomenon of self-defense in the movement. He publicly discouraged it as a widespread practice, but acknowledged that it was sometimes necessary.[55] Throughout his career King was frequently protected by other civil rights activists who carried arms, such as Colonel Stone Johnson,[56] Robert Hayling, and the Deacons for Defense and Justice.[57][58]

Politics

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate: "I feel someone must remain in the position of non-alignment, so that he can look objectively at both parties and be the conscience of both—not the servant or master of either."[59] In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, "I don't think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses ... And I'm not inextricably bound to either party."[60] King did praise Democratic Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois as being the "greatest of all senators" because of his fierce advocacy for civil rights causes over the years.[61]

King critiqued both parties' performance on promoting racial equality:

Although King never publicly supported a political party or candidate for president, in a letter to a civil rights supporter in October 1956 he said that he was undecided as to whether he would vote for Adlai Stevensonor Dwight Eisenhower, but that "In the past I always voted the Democratic ticket."[63] In his autobiography, King says that in 1960 he privately voted for Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy: "I felt that Kennedy would make the best president. I never came out with an endorsement. My father did, but I never made one." King adds that he likely would have made an exception to his non-endorsement policy for a second Kennedy term, saying "Had President Kennedy lived, I would probably have endorsed him in 1964."[64] In 1964, King urged his supporters "and all people of goodwill" to vote against Republican Senator Barry Goldwater for president, saying that his election "would be a tragedy, and certainly suicidal almost, for the nation and the world."[65] King supported the ideals of democratic socialism, although he was reluctant to speak directly of this support due to the anti-communist sentiment being projected throughout America at the time, and the association of socialism with communism. King believed that capitalism could not adequately provide the basic necessities of many American people, particularly the African American community.[66]

Compensation

King stated that black Americans, as well as other disadvantaged Americans, should be compensated for historical wrongs. In an interview conducted for Playboy in 1965, he said that granting black Americans only equality could not realistically close the economic gap between them and whites. King said that he did not seek a full restitution of wages lost to slavery, which he believed impossible, but proposed a government compensatory program of $50 billion over ten years to all disadvantaged groups.[67]

He posited that "the money spent would be more than amply justified by the benefits that would accrue to the nation through a spectacular decline in school dropouts, family breakups, crime rates, illegitimacy, swollen relief rolls, rioting and other social evils".[68] He presented this idea as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor, but clarified that he felt that the money should not be spent exclusively on blacks. He stated, "It should benefit the disadvantaged of all races".[69]

The lack of attention given to family planning

On being awarded the Planned Parenthood Federation of America's Margaret Sanger Award on 5th May, 1966, King said:

Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955

Main articles: Montgomery Bus Boycott and Jim Crow laws § Public arena

In March 1955, a fifteen-year-old school girl in Montgomery, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in compliance with Jim Crow laws, laws in the US South that enforced racial segregation. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case; because Colvin was pregnant and unmarried, E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue.[72]

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat.[73] The Montgomery Bus Boycott, urged and planned by Nixon and led by King, soon followed.[74] The boycott lasted for 385 days,[75] and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed.[76] King was arrested during this campaign, which concluded with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses.[77][78] King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.[79]

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. One of the group's inspirations was the crusades of evangelist Billy Graham, who befriended King after he attended a Graham crusade in New York City in 1957.[80] King led the SCLC until his death.[81] The SCLC's 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was the first time King addressed a national audience.[82]

On September 20, 1958, while signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in Blumstein's department store in Harlem,[83] King narrowly escaped death when Izola Curry, a mentally ill black woman who believed he was conspiring against her with communists, stabbed him in the chest with a letter opener. After emergency surgery, King was hospitalized for several weeks, while Curry was found mentally incompetent to stand trial.[84][85] In 1959, he published a short book called The Measure of A Man, which contained his sermons "What is Man?" and "The Dimensions of a Complete Life". The sermons argued for man's need for God's love and criticized the racial injustices of Western civilization.[86]

Harry Wachtel—who joined King's legal advisor Clarence B. Jones in defending four ministers of the SCLC in a libel suit over a newspaper advertisement (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan)—founded a tax-exempt fund to cover the expenses of the suit and to assist the nonviolent civil rights movement through a more effective means of fundraising. This organization was named the "Gandhi Society for Human Rights". King served as honorary president for the group. Displeased with the pace of President Kennedy's addressing the issue of segregation, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document in 1962 calling on the President to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and use an Executive Order to deliver a blow for Civil Rights as a kind of Second Emancipation Proclamation - Kennedy did not execute the order.[87]

The FBI, under written directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began tapping King's telephone in the fall of 1963.[88] Concerned that allegations of communists in the SCLC, if made public, would derail the administration's civil rights initiatives, Kennedy warned King to discontinue the suspect associations, and later felt compelled to issue the written directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and other SCLC leaders.[89] J. Edgar Hoover feared Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.[90]

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the Civil RightsMovement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.[91][92]

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights.[78] Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[93][94]

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.[95]

Throughout his participation in the civil rights movement, King was criticized by many groups. This included opposition by more militant blacks such as Nation of Islam member Malcolm X.[96] Stokely Carmichael was a separatist and disagreed with King's plea for racial integration because he considered it an insult to a uniquely African-American culture.[97] Omali Yeshitela urged Africans to remember the history of violent European colonization and how power was not secured by Europeans through integration, but by violence and force.[98]

Albany Movement

Main article: Albany Movement

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. In December, King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel."[99] The following day he was swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. According to King, "that agreement was dishonored and violated by the city" after he left town.[99]

King returned in July 1962, and was sentenced to forty-five days in jail or a $178 fine. He chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Police Chief Laurie Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools ... ejected from churches ... and thrown into jail ... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail."[100] It was later acknowledged by the King Center that Billy Graham was the one who bailed King out of jail during this time.[101]

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote nonviolence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts.[102] Though the Albany effort proved a key lesson in tactics for Dr. King and the national civil rights movement,[103] the national media was highly critical of King's role in the defeat, and the SCLC's lack of results contributed to a growing gulf between the organization and the more radical SNCC. After Albany, King sought to choose engagements for the SCLC in which he could control the circumstances, rather than entering into pre-existing situations.[104]

Birmingham campaign

Main article: Birmingham campaign

In April 1963, the SCLC began a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. The campaign used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker. Black people in Birmingham, organizing with the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating laws that they considered unjust.

King's intent was to provoke mass arrests and "create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation".[105] However, the campaign's early volunteers did not succeed in shutting down the city, or in drawing media attention to the police's actions. Over the concerns of an uncertain King, SCLC strategist James Bevelchanged the course of the campaign by recruiting children and young adults to join in the demonstrations.[106] Newsweek called this strategy a Children's Crusade.[107][108]

During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs against protesters, including children. Footage of the police response was broadcast on national television news and dominated the nation's attention, shocking many white Americans and consolidating black Americans behind the movement.[109] Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. But the campaign was a success: Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs came down, and public places became more open to blacks. King's reputation improved immensely.[107]

King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign—his 13th arrest[110] out of 29.[111] From his cell, he composed the now-famous Letter from Birmingham Jail which responds to calls on the movement to pursue legal channels for social change. King argues that the crisis of racism is too urgent, and the current system too entrenched: "We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."[112] He points out that the Boston Tea Party, a celebrated act of rebellion in the American colonies, was illegal civil disobedience, and that, conversely, "everythingAdolf Hitler did in Germany was 'legal'".[112] King also expresses his frustration with white moderates and clergymen too timid to oppose an unjust system:

St. Augustine, Florida

Main article: St. Augustine movement

In March 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with Robert Hayling's then-controversial movement in St. Augustine, Florida. Hayling's group had been affiliated with the NAACP but was forced out of the organization for advocating armed self-defense alongside nonviolent tactics. Ironically, the pacifist SCLC accepted them.[113] King and the SCLC worked to bring white Northern activists to St. Augustine, including a delegation of rabbis and the 72-year-old mother of the governor of Massachusetts, all of whom were arrested.[114][115] During June, the movement marched nightly through the city, "often facing counter demonstrations by the Klan, and provoking violence that garnered national media attention." Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and jailed. During the course of this movement, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.[116]

Selma, Alabama

Main article: Selma to Montgomery marches

In December 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, where the SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months.[117]A local judge issued an injunction that barred any gathering of 3 or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL, or any of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965.[118]

New York City

On February 6, 1964, King delivered the inaugural speech of a lecture series initiated at the New School called "The American Race Crisis". No audio record of his speech has been found, but in August 2013, almost 50 years later, the school discovered an audiotape with 15 minutes of a question-and-answer session that followed King's address. In these remarks, King referred to a conversation he had recently had withJawaharlal Nehru in which he compared the sad condition of many African Americans to that of India's untouchables.[119]

March on Washington, 1963

Main article: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

King, representing the SCLC, was among the leaders of the so-called "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on August 28, 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were Roy Wilkins from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James L. Farmer, Jr., of the Congress of Racial Equality.[120]

The primary logistical and strategic organizer was King's colleague Bayard Rustin.[121] For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march.[122][123] Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation. However, the organizers were firm that the march would proceed.[124] With the march going forward, the Kennedys decided it was important to work to ensure its success. President Kennedy was concerned the turnout would be less than 100,000. Therefore, he enlisted the aid of additional church leaders and the UAW union to help mobilize demonstrators for the cause.[125]

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern U.S. and an opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks. However, the group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.[126] As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington", and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.[126][127]

The march did, however, make specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public schools; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers; and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee.[128][129][130] Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success.[131] More than a quarter of a million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington, D.C.'s history.[131]

King delivered a 17-minute speech, later known as "I Have a Dream". In the speech's most famous passage—in which he departed from his prepared text, possibly at the prompting ofMahalia Jackson, who shouted behind him, "Tell them about the dream!"[132][133]—King said:[134]

"I Have a Dream" came to be regarded as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory.[135] The March, and especially King's speech, helped put civil rights at the top of the agenda of reformers in the United States and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[136][137]

The original, typewritten copy of the speech, including Dr. King's handwritten notes on it, was discovered in 1984 to be in the hands of George Raveling, the first African-American basketball coach of the University of Iowa. In 1963, Raveling, then 26, was standing near the podium, and immediately after the oration, impulsively asked King if he could have his copy of the speech. He got it.[138]

Selma Voting Rights Movement and "Bloody Sunday", 1965

Main article: Selma to Montgomery marches

Acting on James Bevel's call for a march from Selma to Montgomery, King, Bevel, and the SCLC, in partial collaboration with SNCC, attempted to organize the march to the state's capital. The first attempt to march on March 7, 1965, was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has become known as Bloody Sunday, and was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the Civil Rights Movement. It was the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King's nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present.[139]

King met with officials in the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration on March 5 in order to request an injunction against any prosecution of the demonstrators. He did not attend the march due to church duties, but he later wrote, "If I had any idea that the state troopers would use the kind of brutality they did, I would have felt compelled to give up my church duties altogether to lead the line."[140] Footage of police brutality against the protesters was broadcast extensively and aroused national public outrage.[141]

King next attempted to organize a march for March 9. The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in federal court against the State of Alabama; this was denied and the judge issued an order blocking the march until after a hearing. Nonetheless, King led marchers on March 9 to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, then held a short prayer session before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement.[142] The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, 1965.[143][144] At the conclusion of the march on the steps of the state capitol, King delivered a speech that became known as "How Long, Not Long". In it, King stated that equal rights for African Americans could not be far away, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice".[a][145][146]

Chicago Open Housing Movement, 1966

Main article: Chicago Freedom Movement

In 1966, after several successes in the South, King, Bevel, and others in the civil rights organizations tried to spread the movement to the North, with Chicago as their first destination. King and Ralph Abernathy, both from the middle class, moved into a building at 1550 S. Hamlin Ave., in the slums of North Lawndale[147] on Chicago's West Side, as an educational experience and to demonstrate their support and empathy for the poor.[148]

The SCLC formed a coalition with CCCO, Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, an organization founded by Albert Raby, and the combined organizations' efforts were fostered under the aegis of the Chicago Freedom Movement.[149] During that spring, several white couple / black couple tests of real estate offices uncovered racial steering: discriminatory processing of housing requests by couples who were exact matches in income, background, number of children, and other attributes.[150] Several larger marches were planned and executed: in Bogan, Belmont Cragin, Jefferson Park, Evergreen Park (a suburb southwest of Chicago), Gage Park, Marquette Park, and others.[149][151][152]

Abernathy later wrote that the movement received a worse reception in Chicago than in the South. Marches, especially the one through Marquette Park on August 5, 1966, were met by thrown bottles and screaming throngs. Rioting seemed very possible.[153][154] King's beliefs militated against his staging a violent event, and he negotiated an agreement with Mayor Richard J. Daley to cancel a march in order to avoid the violence that he feared would result.[155] King was hit by a brick during one march but continued to lead marches in the face of personal danger.[156]

When King and his allies returned to the South, they left Jesse Jackson, a seminary student who had previously joined the movement in the South, in charge of their organization.[157] Jackson continued their struggle for civil rights by organizing the Operation Breadbasket movement that targeted chain stores that did not deal fairly with blacks.[158]

Opposition to the Vietnam War

King long opposed American involvement in the Vietnam War,[159] but at first avoided the topic in public speeches in order to avoid the interference with civil rights goals that criticism of President Johnson's policies might have created.[159] However, at the urging of SCLC's former Director of Direct Action and now the head of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, James Bevel,[160] King eventually agreed to publicly oppose the war as opposition was growing among the American public.[159] In an April 4, 1967, appearance at the New York City Riverside Church—exactly one year before his death—King delivered a speech titled "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence".[161] He spoke strongly against the U.S.'s role in the war, arguing that the U.S. was in Vietnam "to occupy it as an American colony"[162] and calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today".[163] He also connected the war with economic injustice, arguing that the country needed serious moral change:

King also opposed the Vietnam War because it took money and resources that could have been spent on social welfare at home. The United States Congress was spending more and more on the military and less and less on anti-poverty programs at the same time. He summed up this aspect by saying, "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death".[164] He stated that North Vietnam "did not begin to send in any large number of supplies or men until American forces had arrived in the tens of thousands",[165] and accused the U.S. of having killed a million Vietnamese, "mostly children".[166] King also criticized American opposition to North Vietnam's land reforms.[167]

King's opposition cost him significant support among white allies, including President Johnson, Billy Graham,[168] union leaders and powerful publishers.[169] "The press is being stacked against me", King said,[170]complaining of what he described as a double standard that applauded his nonviolence at home, but deplored it when applied "toward little brown Vietnamese children".[171] Life magazine called the speech "demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi",[164] and The Washington Post declared that King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people".[171][172]

The "Beyond Vietnam" speech reflected King's evolving political advocacy in his later years, which paralleled the teachings of the progressive Highlander Research and Education Center, with which he was affiliated.[173][174] King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation, and more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice.[175] He guarded his language in public to avoid being linked to communism by his enemies, but in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism.[176][177] In a 1952 letter to Coretta Scott, he said "I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic..."[178] In one speech, he stated that "something is wrong with capitalism" and claimed, "There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism."[179] King had read Marx while at Morehouse, but while he rejected "traditional capitalism", he also rejected communism because of its "materialistic interpretation of history" that denied religion, its "ethical relativism", and its "political totalitarianism".[180]

King also stated in "Beyond Vietnam" that "true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar ... it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring".[181] King quoted a United States official who said that, from Vietnam to Latin America, the country was "on the wrong side of a world revolution".[181] King condemned America's "alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America", and said that the U.S. should support "the shirtless and barefoot people" in the Third World rather than suppressing their attempts at revolution.[181]

On April 15, 1967, King participated in and spoke at an anti-war march from New York's Central Park to the United Nations organized by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and initiated by its chairman, James Bevel. At the U.N. King also brought up issues of civil rights and the draft.

Seeing an opportunity to unite civil rights activists and anti-war activists,[160] Bevel convinced King to become even more active in the anti-war effort.[160] Despite his growing public opposition towards the Vietnam War, King was also not fond of the hippie culture which developed from the anti-war movement.[183] In his 1967 Massey Lecture, King stated:

On January 13, 1968, the day after President Johnson's State of the Union Address, King called for a large march on Washington against "one of history's most cruel and senseless wars".[184][185]

Poor People's Campaign, 1968

Main article: Poor People's Campaign

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. King traveled the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an "economic bill of rights" for poor Americans.[186][187]

The campaign was preceded by King's final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, which laid out his view of how to address social issues and poverty. King quoted from Henry George and George's book, Progress and Poverty, particularly in support of a guaranteed basic income.[188][189][190] The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C., demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States.

King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America's cities. He felt that Congress had shown "hostility to the poor" by spending "military funds with alacrity and generosity". He contrasted this with the situation faced by poor Americans, claiming that Congress had merely provided "poverty funds with miserliness".[187] His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of "racism, poverty, militarism and materialism", and argued that "reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced".[191]

The Poor People's Campaign was controversial even within the civil rights movement. Rustin resigned from the march, stating that the goals of the campaign were too broad, that its demands were unrealizable, and that he thought that these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.[192]

After King's death

The plan to set up a shantytown in Washington, D.C., was carried out soon after the April 4 assassination. Criticism of King's plan was subdued in the wake of his death, and the SCLC received an unprecedented wave of donations for the purpose of carrying it out. The campaign officially began in Memphis, on May 2, at the hotel where King was murdered.[193]

Thousands of demonstrators arrived on the National Mall and established a camp they called "Resurrection City". They stayed for six weeks.[194]

Assassination and aftermath

Main article: Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of the black sanitary public works employees, represented by AFSCME Local 1733, who had been on strikesince March 12 for higher wages and better treatment. In one incident, black street repairmen received pay for two hours when they were sent home because of bad weather, but white employees were paid for the full day.[195][196][197]

On April 3, King addressed a rally and delivered his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" address at Mason Temple, the world headquarters of the Church of God in Christ. King's flight to Memphis had been delayed by a bomb threat against his plane.[198] In the close of the last speech of his career, in reference to the bomb threat, King said the following:

King was booked in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel, owned by Walter Bailey, in Memphis. Abernathy, who was present at the assassination, testified to the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed at room 306 at the Lorraine Motel so often it was known as the "King-Abernathy suite".[200]According to Jesse Jackson, who was present, King's last words on the balcony before his assassination were spoken to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was attending: "Ben, make sure you play 'Take My Hand, Precious Lord' in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."[201]

Then, at 6:01 p.m., April 4, 1968, a shot rang out as King stood on the motel's second-floor balcony. The bullet entered through his right cheek, smashing his jaw, then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder.[202][203] Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor.[204] Jackson stated after the shooting that he cradled King's head as King lay on the balcony, but this account was disputed by other colleagues of King's; Jackson later changed his statement to say that he had "reached out" for King.[205]

After emergency chest surgery, King died at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m.[206] According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though only 39 years old, he "had the heart of a 60 year old", which Branch attributed to the stress of 13 years in the Civil Rights Movement.[207]

Aftermath

Further information: King assassination riots

The assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots in Washington, D.C.; Chicago; Baltimore; Louisville; Kansas City; and dozens of other cities.[208][209] Presidential candidate Robert F. "Bobby" Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis for a campaign rally when he was informed of King's death. He gave a short speech to the gathering of supporters informing them of the tragedy and urging them to continue King's ideal of nonviolence.[210] James Farmer, Jr., and other civil rights leaders also called for nonviolent action, while the more militant Stokely Carmichael called for a more forceful response.[211] The city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on terms favorable to the sanitation workers.[212]

President Lyndon B. Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the civil rights leader.[213] Vice President Hubert Humphrey attended King's funeral on behalf of the President, as there were fears that Johnson's presence might incite protests and perhaps violence.[214] At his widow's request, King's last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church was played at the funeral,[215] a recording of his "Drum Major" sermon, given on February 4, 1968. In that sermon, King made a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry", "clothe the naked", "be right on the [Vietnam] war question", and "love and serve humanity".[216] His good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord", at the funeral.[217]

Two months after King's death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd on his way to white-ruled Rhodesia.[218] Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, though he recanted this confession three days later.[219] On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray pled guilty to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. He was sentenced to a 99-year prison term.[219][220]Ray later claimed a man he met in Montreal, Quebec, with the alias "Raoul" was involved and that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy.[221][222] He spent the remainder of his life attempting, unsuccessfully, to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had.[220]

Allegations of conspiracy

Ray's lawyers maintained he was a scapegoat similar to the way that John F. Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald is seen by conspiracy theorists.[223] Supporters of this assertion say that Ray's confession was given under pressure and that he had been threatened with the death penalty.[220][224] They admit Ray was a thief and burglar, but claim he had no record of committing violent crimes with a weapon.[222] However, prison records in different U.S. cities have shown that he was incarcerated on numerous occasions for charges of armed robbery.[225] In a 2008 interview with CNN, Jerry Ray, the younger brother of James Earl Ray, claimed that James was smart and was sometimes able to get away with armed robbery. Jerry Ray said that he had assisted his brother on one such robbery. "I never been with nobody as bold as he is," Jerry said. "He just walked in and put that gun on somebody, it was just like it's an everyday thing."[225]

Those suspecting a conspiracy in the assassination point to the two successive ballistics tests which proved that a rifle similar to Ray's Remington Gamemaster had been the murder weapon. Those tests did not implicate Ray's specific rifle.[220][226] Witnesses near King at the moment of his death said that the shot came from another location. They said that it came from behind thick shrubbery near the boarding house—which had been cut away in the days following the assassination—and not from the boarding house window.[227] However, Ray's fingerprints were found on various objects (a rifle, a pair of binoculars, articles of clothing, a newspaper) that were left in the bathroom where it was determined the gunfire came from.[225] An examination of the rifle containing Ray's fingerprints also determined that at least one shot was fired from the firearm at the time of the assassination.[225]

In 1997, King's son Dexter Scott King met with Ray, and publicly supported Ray's efforts to obtain a new trial.[228]

Two years later, Coretta Scott King, King's widow, along with the rest of King's family, won a wrongful death claim against Loyd Jowers and "other unknown co-conspirators". Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King's assassination. The jury of six whites and six blacks found in favor of the King family, finding Jowers to be complicit in a conspiracy against King and that government agencies were party to the assassination.[229][230] William F. Pepper represented the King family in the trial.[231]

In 2000, the U.S. Department of Justice completed the investigation into Jowers' claims but did not find evidence to support allegations about conspiracy. The investigation report recommended no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.[232] A sister of Jowers admitted that he had fabricated the story so he could make $300,000 from selling the story, and she in turn corroborated his story in order to get some money to pay her income tax.[233][234]

In 2002, The New York Times reported that a church minister, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson, claimed his father, Henry Clay Wilson—not James Earl Ray—assassinated King. He stated, "It wasn't a racist thing; he thought Martin Luther King was connected with communism, and he wanted to get him out of the way." Wilson provided no evidence to back up his claims.[235]

King researchers David Garrow and Gerald Posner disagreed with William F. Pepper's claims that the government killed King.[236] In 2003, William Pepper published a book about the long investigation and trial, as well as his representation of James Earl Ray in his bid for a trial, laying out the evidence and criticizing other accounts.[237] King's friend and colleague, James Bevel, also disputed the argument that Ray acted alone, stating, "There is no way a ten-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar black man."[238] In 2004, Jesse Jackson stated:

FBI and King's personal lifeFBI surveillance and wiretapping

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover personally ordered surveillance of King, with the intent to undermine his power as a civil rights leader.[169][240] According to the Church Committee, a 1975 investigation by the U.S. Congress, "From December 1963 until his death in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was the target of an intensive campaign by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to 'neutralize' him as an effective civil rights leader."[241]

The Bureau received authorization to proceed with wiretapping from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in the fall of 1963[242] and informed President John F. Kennedy, both of whom unsuccessfully tried to persuade King to dissociate himself from Stanley Levison, a New York lawyer who had been involved with Communist Party USA.[243][244] Although Robert Kennedy only gave written approval for limited wiretapping of King's phones "on a trial basis, for a month or so",[245] Hoover extended the clearance so his men were "unshackled" to look for evidence in any areas of King's life they deemed worthy.[246] The Bureau placed wiretaps on Levison's and King's home and office phones, and bugged King's rooms in hotels as he traveled across the country.[243][247] In 1967, Hoover listed the SCLC as a black nationalist hate group, with the instructions: "No opportunity should be missed to exploit through counterintelligence techniques the organizational and personal conflicts of the leaderships of the groups ... to insure the targeted group is disrupted, ridiculed, or discredited."[240][248]

NSA monitoring of King's communications

In a secret operation code-named "Minaret", the National Security Agency (NSA) monitored the communications of leading Americans, including King, who criticized the U.S. war in Vietnam.[249] A review by the NSA itself concluded that Minaret was "disreputable if not outright illegal."[249]

Allegations of communism

For years, Hoover had been suspicious about potential influence of communists in social movements such as labor unions and civil rights.[250] Hoover directed the FBI to track King in 1957, and the SCLC as it was established (it did not have a full-time executive director until 1960).[90] The investigations were largely superficial until 1962, when the FBI learned that one of King's most trusted advisers was New York City lawyer Stanley Levison.[251]