Dr. W.V. Cordice Jr., 94, a Surgeon Who Helped Save Dr. King, Dies

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Published: January 3, 2014

On Sept. 20, 1958, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then emerging as the leader of the civil rights movement, was autographing copies of his new book in a Harlem department store when a woman approached to greet him. He nodded without looking up. Then she stabbed him in the chest with a razor-sharp seven-inch letter opener.

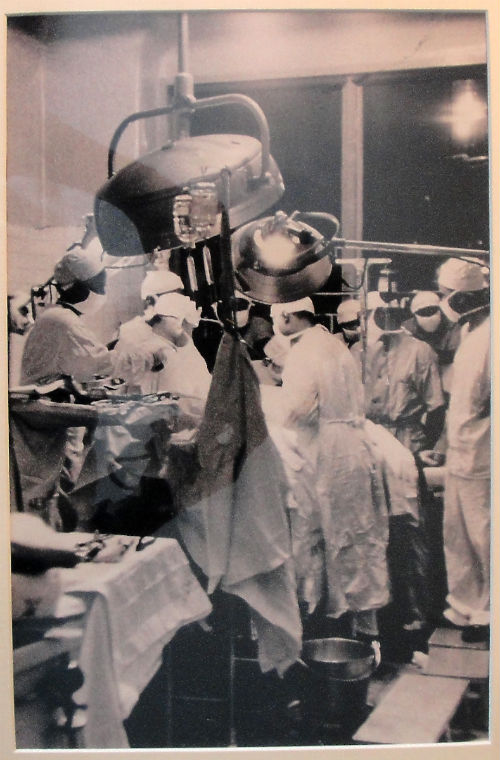

John Lent/Associated Press

Dr. Cordice operated on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Harlem Hospital.

Dr. King, then 29, was taken to Harlem Hospital, where three surgeons went to work. The blade had missed his aorta by millimeters, and doctors said a sneeze could have caused him to bleed to death. After mapping out a strategy, they used a hammer and chisel to crack Dr. King’s sternum, and repaired the wound in two and a half hours.

On Dec. 29, the last surviving surgeon from that hospital team, Dr. W. V. Cordice Jr., died at 94 in Sioux City, Iowa, his granddaughter Jennifer Fournier said. He had moved to Iowa in November to be near family.

“I think if we had lost King that day, the whole civil rights era could have been different,” Dr. Cordice said in a Harlem Hospital promotional video in 2012.

New York’s governor at the time, W. Averell Harriman, who raced to the hospital to observe the surgery, had requested that black doctors be involved if at all possible, Hugh Pearson reported in his 2002 book, “When Harlem Nearly Killed King.” Dr. Cordice and Dr. Aubré de Lambert Maynard, the hospital’s chief of surgery, were African-American. The third surgeon, Dr. Emil Naclerio, was Italian-American.

Over the years, Dr. Maynard was widely credited with saving Dr. King — and he accepted that credit — but in a 2012 interview with the public radio station WNYC, Dr. Cordice said that he and Dr. Naclerio had performed the surgery.

“We were not going to challenge him, because he was the boss,” Dr. Cordice said of Dr. Maynard.

Alan D. Aviles, the president of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, suggested that Dr. Cordice’s modesty may also have kept him from getting the credit he deserved. “It is entirely consistent with his character that many who knew him may well not have known that he was also part of history,” Mr. Aviles said in a statement.

At the time of the stabbing, Dr. King was promoting his book “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,” which recounted the successful boycott he helped lead to desegregate buses in Montgomery, Ala. His assailant was a mentally disturbed black woman who blamed Dr. King for her woes. Dr. King forgave her and asked that she not be prosecuted. He later learned that she had been committed to a hospital for the criminally insane.

John Walter Vincent Cordice Jr. was born in Aurora, N.C., on June 16, 1919. His father, a physician, worked for the United States Public Health Service there, fighting the flu epidemic of 1918. The family moved to Durham, N.C., when John was 6. He graduated from high school a year early, and then from New York University and its medical school.

With the outbreak of World War II, he interrupted his internship at Harlem Hospital to serve as a doctor for the Tuskegee Airmen, the famed group of African-American pilots. After the war, and after completing the internship, he held a succession of residencies. In 1955-56 he studied in Paris, where he was part of the team that performed the first open-heart surgery in France.

Dr. Cordice later became chief of thoracic and vascular surgery at Harlem Hospital, the position he held when he treated Dr. King. He went on to hold the same post at Queens Hospital Center. He was president of the Queens Medical Society in 1983-84.

Dr. Cordice, who lived in Hollis, Queens, for many years before moving to Iowa, is survived by his wife of 65 years, the former Marguerite Smith; his daughters, Michele Boykin, Jocelyn Basnett and Marguerite D. Cordice; his sister, Marion Parhan; six grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Dr. Naclerio died in 1985, Dr. Maynard in 1999.

Dr. King wrote thank-you letters to all three surgeons. In his last public speech before his assassination in 1968, he reflected on the implications of his surviving the stabbing.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around in 1960, when students all over the South started sitting in at lunch counters,” he said. “If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1961, when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation in interstate travel.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been here in 1963, when the black people of Birmingham, Ala., aroused the conscience of this nation, and brought into being the Civil Rights Bill. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream I had.”

*****

Play

00:00 / 00:00

Dr. John Cordice and his wife Marguerite. Dr. Cordice performed life-saving surgery in 1958 on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after the civil rights leader was stabbed in the chest in Harlem. (Tracie Hunte)

Dr. John Cordice and his wife Marguerite. Dr. Cordice performed life-saving surgery in 1958 on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after the civil rights leader was stabbed in the chest in Harlem. (Tracie Hunte)

Fifty-four years ago this month, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was in Harlem signing copies of his book, when a mentally disturbed woman plunged a steel letter opener into his chest.

The wound punctured his sternum, mere inches away from his aorta. King was taken to Harlem Hospital where his life and the course of history hung in the balance.

He recovered, of course, but was later assassinated in 1968. And now the last surviving member of the surgical team that saved his life is being honored by Harlem Hospital Thursday night as it unveils its historic WPA murals.

At 93, Dr. John Cordice has a slight build, close-cropped white hair and a friendly smile. He and his wife, Marguerite, celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary on Monday and their home in Hollis, Queens, is filled with the flowers and greetings cards they exchanged.

He grew up in Durham, N.C., and moved to New York City in 1936. He earned his medical degree at New York University in 1943 and went on to serve as an Attending Surgeon and Chief of Thoracic Surgery at both Harlem Hospital and the Queens Hospital Center, according to the hospital.

He says on September 20, 1958, he was with his daughter in Brooklyn picking up mail at his office when he got a call from Harlem Hospital telling him an important person was suffering from a life-threatening injury.

“We raced on in to Harlem Hospital and when I went into the emergency room, of course, the crowd was beginning to gather and then I was informed that Dr. King had been injured,” Cordice said.

He reviewed King’s X-rays with fellow surgeon Dr. Emil Naclerio and consulted with their chief of surgery Dr. Aubrey Maynard.

He reviewed King’s X-rays with fellow surgeon Dr. Emil Naclerio and consulted with their chief of surgery Dr. Aubrey Maynard.

For many years, it would be Maynard who received most of the credit for saving King’s life, even though Cordice and Naclerio performed the surgery.

(Photo: This photo of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the operating room following his stabbing on September 20, 1958 hangs in Cordice's home.Courtesy Dr. John Cordice)

“He decided it would be better if he assumed a principal role here, in spite of the fact that he did not do the surgery,” Cordice said. “We were not going to challenge him because actually he was the boss.”

Harlem Hospital had its own impact on the civil rights movement. Dr. Louis T. Wright was the first African-American on the hospital’s surgical staff and also served as chairman of the national board of directors for the NAACP. And as Hugh Pearson wrote in his book, When Harlem Nearly Killed King, the hospital was the most integrated of any in the country.

“Wright had died before this event occurred, but his record and his history and his relationship to the NAACP were still very much alive, and so we felt a certain personal identity and a personal responsibility to carry through a level of performance professionally which would make him proud,” Cordice said.

In his last speech on April 3, 1968, Dr. King reflected on just how close he’d come to dying that fateful night. Doctors had told him that if he had sneezed, he would’ve died.

“I want to say tonight, I’m too am happy I didn’t sneeze, because if I had sneezed I wouldn’t have been around in 1960 when students all over the south started sitting in at lunch counters,” he said.

King continued: “If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around in 1961 when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation in interstate travel...If I had sneezed … I wouldn’t have been able to tell America about a dream that I had had.”

(Photo: Cordice sits in his home with a photo of the operating room the night Dr. King was stabbed. Tracie Hunte/WNYC)

MORE IN:

******

John Walter Vincent Cordice, Jr. (b. June 16, 1919, Aurora, North Carolina - d. December 29, 2013, Sioux City, Iowa) was one of the surgeon's who operated on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1958 after King had been stabbed in the chest.

On September 20, 1958, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., then emerging as the leader of the civil rights movement, was autographing copies of his new book in a Harlem department store when a woman approached to greet him. He nodded without looking up. Then she stabbed him in the chest with a razor-sharp seven-inch letter opener.

Dr. King, then 29, was taken to Harlem Hospital, where three surgeons went to work. The blade had missed his aorta by millimeters, and doctors said a sneeze could have caused him to bleed to death. After mapping out a strategy, they used a hammer and chisel to crack Dr. King’s sternum, and repaired the wound in two and a half hours.

New York’s governor at the time, W. Averell Harriman, who raced to the hospital to observe the surgery, had requested that black doctors be involved if at all possible, Hugh Pearson reported in his 2002 book, “When Harlem Nearly Killed King.” Dr. Cordice and Dr. Aubré de Lambert Maynard, the hospital’s chief of surgery, were African-American. The third surgeon, Dr. Emil Naclerio, was Italian-American.

Over the years, Dr. Maynard was widely credited with saving Dr. King — and he accepted that credit — but in a 2012 interview with the public radio station WNYC, Dr. Cordice said that he and Dr. Naclerio had performed the surgery.

“We were not going to challenge him, because he was the boss,” Dr. Cordice said of Dr. Maynard.

Alan D. Aviles, the president of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, suggested that Dr. Cordice’s modesty may also have kept him from getting the credit he deserved. “It is entirely consistent with his character that many who knew him may well not have known that he was also part of history,” Mr. Aviles said in a statement.

At the time of the stabbing, Dr. King was promoting his book “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,” which recounted the successful boycott he helped lead to desegregate buses in Montgomery, Alabama. His assailant was a mentally disturbed black woman who blamed Dr. King for her woes. Dr. King forgave her and asked that she not be prosecuted. He later learned that she had been committed to a hospital for the criminally insane.

John Walter Vincent Cordice Jr. was born in Aurora, North Carolina, on June 16, 1919. His father, a physician, worked for the United States Public Health Service there, fighting the flu epidemic of 1918. The family moved to Durham, North Carolina, when John was 6. He graduated from high school a year early, and then from New York University and its medical school.

With the outbreak of World War II, he interrupted his internship at Harlem Hospital to serve as a doctor for the Tuskegee Airmen, the famed group of African-American pilots. After the war, and after completing the internship, he held a succession of residencies. In 1955-56 he studied in Paris, where he was part of the team that performed the first open-heart surgery in France.

Dr. Cordice later became chief of thoracic and vascular surgery at Harlem Hospital, the position he held when he treated Dr. King. He went on to hold the same post at Queens Hospital Center. He was president of the Queens Medical Society in 1983-84.

On December 29, the last surviving surgeon from that hospital team, Dr. W. V. Cordice Jr., died at 94 in Sioux City, Iowa.

On December 29, the last surviving surgeon from that hospital team, Dr. W. V. Cordice Jr., died at 94 in Sioux City, Iowa.

Dr. Cordice, who lived in Hollis, Queens, for many years before moving to Iowa, was survived by his wife of 65 years, the former Marguerite Smith; his daughters, Michele Boykin, Jocelyn Basnett and Marguerite D. Cordice; his sister, Marion Parhan; six grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

No comments:

Post a Comment