88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

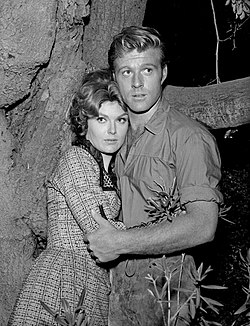

Robert Redford | |

|---|---|

Redford in 1971 | |

| Born | Charles Robert Redford Jr. August 18, 1936 Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Died | September 16, 2025 (aged 89) Sundance, Utah, U.S.[1] |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1959–2025 |

| Works | Full list |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 4, including James and Amy |

| Awards | Full list |

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Robert Redford (born August 18, 1936, Santa Monica, California, U.S.—died September 16, 2025, Sundance, Utah county, Utah) was an American motion-picture actor and director known for his boyish good looks and diversity of screen characterizations. He gained wide fame with his performance opposite Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and thereafter became a highly sought-after leading man, starring in such notable hits as The Way We Were (1973), The Sting (1973), All the President’s Men (1976), and Out of Africa (1985). Redford was also known for his lifelong commitment to environmental and liberal political causes and for founding the Sundance Institute and promoting the Sundance Film Festival in Utah, which he used to advocate for independent filmmaking and mentor young directors.

Early life and career

Redford’s father was a milkman who later became an accountant, and his mother was a homemaker who died when he was in his teens. Growing up in and around Los Angeles, he had early contact with show business, attending schools with the children of actors and producers such as Dore Schary. Redford briefly attended the University of Colorado on a baseball scholarship but dropped out and spent several years drifting and studying art in Europe and the United States. Redford enrolled at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City and soon after made his Broadway debut in the play Tall Story (1959). Landing roles in several television dramas of the early 1960s, such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, and Route 66, he scored the biggest triumph of his early career with the lead role in Neil Simon’s Broadway hit Barefoot in the Park (1963).

Stardom: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Way We Were

Redford appeared in mostly forgettable films throughout the mid-1960s, the cult favorite The Chase (1966) and the screen adaptation of Barefoot in the Park (1967) being notable exceptions. The turning point in his career came when he starred with Paul Newman in the enormously popular comic western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), in which he portrayed the outlaw Sundance Kid. The film was the top-grossing picture of the year, and Redford was soon one of Hollywood’s most popular and bankable stars.

He next appeared in such successful films as Downhill Racer (1969; written by James Salter) and The Candidate (1972). He starred with Barbra Streisand in The Way We Were and reteamed with Newman in The Sting—the two most successful films of 1973—and was ranked as the top American box-office attraction. The Sting won that year’s Academy Award for best picture and earned Redford his only Oscar nomination for acting.

Other Redford films of the 1970s include Jeremiah Johnson (1972), The Great Gatsby (1974), The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), and Three Days of the Condor (1975), but they were overshadowed by All the President’s Men (1976). An account of the downfall of the administration of U.S. Pres. Richard Nixon, the film starred Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, respectively. It garnered Oscar nominations in eight categories and firmly established Redford’s star status.

Redford thereafter became much more selective about his roles and typically went several years between screen appearances. He starred in The Natural (1984), an adaptation of the Bernard Malamud novel about mythical baseball hero Roy Hobbs, which earned four Oscar nominations. Out of Africa (1985), in which he appeared opposite Meryl Streep, won 7 of the 11 Oscars for which it was nominated.

Later films

Although Redford had become established as a Hollywood icon, he was generally unable to repeat his early level of success in his later films. Sneakers (1992), The Horse Whisperer (1998), Spy Game (2001), and The Clearing (2004) earned mixed reviews. Better received was All Is Lost (2013), in which he played a sailor whose yacht is struck by a shipping container; the tense survival drama featured little dialogue, and Redford was the only actor.

He then made an uncharacteristic appearance in a big-budget studio release, as the undercover agent Alexander Pierce in the Marvel comic book action film Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014). He and Nick Nolte headlined the buddy comedy A Walk in the Woods (2015), which was based on the memoir (1998) by writer Bill Bryson. Redford portrayed CBS reporter Dan Rather in the newsroom drama Truth (2015), which concerns the backlash from a story about U.S. Pres. George W. Bush’s military service. Redford then starred in a remake of Pete’s Dragon, a family film from Disney.

In 2017 he played a widower befriended by his longtime neighbor (played by Jane Fonda) in the Netflix movie Our Souls at Night. The next year Redford portrayed a bank robber with charming manners in The Old Man & the Gun. He reprised the role of Pierce in Marvel’s Avengers: Endgame (2019). His final screen role was a 2025 cameo in Dark Winds (2022– ), a detective series set in the Navajo Nation and based on the work of novelist Tony Hillerman; Redford coproduced the show.

Directing: Ordinary People and A River Runs Through It

Redford launched his directing career with Ordinary People (1980), a family drama adapted from a novel by Judith Guest. The film won best picture at the Academy Awards, and Redford won an Oscar for best director. Of Redford’s first seven directorial efforts, The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), The Horse Whisperer, The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000), and Lions for Lambs (2007) garnered lukewarm reviews, but Ordinary People, A River Runs Through It (1992), and Quiz Show (1994) are regarded as minor masterpieces. The latter film, which dramatized a 1950s quiz-show scandal, earned four Oscar nominations, including best picture and best director.

Redford subsequently directed The Conspirator (2010), about the trial of Mary Surratt, who was accused of having collaborated in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, and The Company You Keep (2012), in which he starred as a family man running from his radical activist past. He also directed a segment about the Salk Institute for Biological Studies building in La Jolla, California, designed by Louis Kahn, for the architectural documentary anthology film Cathedrals of Culture (2014). Redford’s directing style is characterized by long, meditative takes and by an emotional detachment from subject matter that serves to heighten the irony of the narrative.

Sundance Institute and Sundance Film Festival

In the late 1960s Redford purchased several thousand acres of mountain wilderness in Provo Canyon, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Provo, Utah. He named it Sundance, after his breakout role, and opened a ski resort. In 1980 Redford established the Sundance Institute at the site as a vehicle to support independent filmmakers whose work did not fit into the constraints of Hollywood studios. The institute became known for hosting “labs” each year, in which established filmmakers provided workshops and guidance to young directors and screenwriters starting their careers; notable past participants include Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Chloé Zhao.

Since 1985 the institute has also sponsored the annual Sundance Film Festival in nearby Park City, Utah. By the 1990s the festival had become one of the leading international film festivals, and it continues to be regarded as a vital showcase for new talent. Numerous directors premiered their debut films at the festival, including the Coen brothers (Blood Simple [1985]), Steven Soderbergh (sex, lies, and videotape [1989]), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs [1992]), and Zhao (Songs My Brothers Taught Me [2015]).

Activism and honors

In addition to his film career, Redford was known as an outspoken activist, especially for environmental protection and Indigenous and LGBTQ rights. Some of his political activities included fighting against the building of a coal power plant in what later became Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, in southern Utah; serving as a trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council; and supporting same-sex marriage campaigns in the 2010s.

For his work with Sundance and other contributions to film, Redford was presented with an honorary Academy Award in 2002. His numerous other awards include the National Medal of the Arts (1996), Kennedy Center Honors (2005), the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2008), and the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom (2016).

Personal life

Redford married Lola Van Wagenen in 1958. They had four children and divorced in 1985. He married Sibylle Szaggars in 2009.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Charles Robert Redford Jr. (August 18, 1936 – September 16, 2025) was an American actor, director, and producer. He was known as a leading man who gained stardom during the American New Wave. Over a career spanning more than six decades, he received numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Film Award, five Golden Globe Awards (including the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1994). Redford also received various honors including the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award in 1996, the Academy Honorary Award in 2002, the Kennedy Center Honors in 2005, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016, and the Honorary César in 2019.

Redford began his career on television in the late 1950s, appearing in anthology series such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone. He made his Broadway debut in Neil Simon’s comedy Barefoot in the Park (1963), playing a newlywed opposite Elizabeth Ashley. He soon transitioned to film, taking roles in War Hunt (1962) and Inside Daisy Clover (1965), before achieving stardom with Barefoot in the Park (1967) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). His subsequent performances in Downhill Racer (1969), Jeremiah Johnson (1972), The Candidate (1972), and The Sting (1973) established him as one of Hollywood’s leading actors, with the latter earning him an Academy Award nomination.

His stardom continued with films such as The Way We Were (1973), The Great Gatsby (1974), Three Days of the Condor (1975), All the President’s Men (1976), The Electric Horseman (1979), The Natural (1984), and Out of Africa (1985). Later credits include Sneakers (1992), Indecent Proposal (1993), All Is Lost (2013), Truth (2015), Our Souls at Night (2017), and The Old Man & the Gun (2018). He also played Alexander Pierce in the MCU films Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) and Avengers: Endgame (2019), the latter serving as his final on-screen role.

Redford made his directorial debut with the family drama Ordinary People (1980), which won four Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director. His later directing credits include The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), A River Runs Through It (1992), Quiz Show (1994), The Horse Whisperer (1998), and The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000). A major advocate for independent cinema, Redford co-founded the Sundance Institute and the Sundance Film Festival in 1978, helping to foster a new generation of filmmakers. Beyond his artistic career, he was noted for his environmental activism, his support of Native American and Indigenous rights, and his advocacy for LGBTQ equality.

Early life and education

Charles Robert Redford Jr. was born on August 18, 1936,[1] in Santa Monica, California, to Martha Woodruff Redford (née Hart; 1914–1955), who was from Austin, Texas, and Charles Robert Redford Sr. (1914–1991), an accountant.[2] He had a paternal half-brother, William.[3] Redford was of Irish, Scottish, and English ancestry.[4][page needed][5][6] His patrilineal great-great-grandfather, a Protestant Englishman named Elisha Redford, married Mary Ann McCreery, of Irish Catholic descent, in Manchester, Lancashire. They immigrated to New York City in America in 1849, immediately settling next in Stonington, Connecticut. They had a son named Charles, the first in line to have been given the name. Regarding Redford's maternal lineage, the Harts were Irish from Galway and the Greens were Scotch-Irish who settled in the United States in the 18th century.[4][page needed] Redford's family lived in Van Nuys while his father worked in El Segundo. As a child, he and his family often traveled to Austin to visit his maternal grandfather. Redford credited his environmentalism and love of nature to his childhood in Texas.[7]

Redford attended Van Nuys High School, where he was classmates with baseball pitcher Don Drysdale.[3][8] He described himself as having been a "bad" student, finding inspiration outside the classroom in art and sports.[3] He hit tennis balls with Pancho Gonzalez at the Los Angeles Tennis Club to help Gonzalez warm up for matches. Redford had a mild case of polio when he was 11.[9]

After graduating from high school in 1954,[10] he attended the University of Colorado in Boulder for a year and a half,[3][11][12] where he was a member of Kappa Sigma fraternity.[13] While there, he worked at a restaurant/bar called The Sink, where a painting of his likeness now figures prominently among the bar's murals.[14][better source needed] While at Colorado, Redford began drinking heavily and, as a result, lost his half-scholarship and was expelled from school.[11][12] He went on to travel in Europe, living in France, Spain, and Italy.[3] He later studied painting at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, and took classes at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts (Class of 1959) in Manhattan, New York.[3][15]

Career

1959–1966: Early roles

Redford's acting career began in New York City, where he worked both on stage and in television. His Broadway debut was in a small role in Tall Story (1959), followed by parts in The Highest Tree (1959) and Sunday in New York (1961). His biggest success on Broadway was as the stuffy newlywed husband of Elizabeth Ashley in the original 1963 cast of Neil Simon's Barefoot in the Park.[16] Starting in 1960, Redford appeared as a guest star on numerous television drama programs, including Naked City, Maverick, The Untouchables, The Americans, Whispering Smith, Perry Mason, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Route 66, Dr. Kildare, Playhouse 90, Tate, The Twilight Zone, The Virginian, and Captain Brassbound's Conversion, among others.[17][18]

Redford made his screen debut in the film adaptation of Tall Story (1960), reprising his Broadway role, although he was not credited.[19] The film's stars were Anthony Perkins, Jane Fonda (her debut), and Ray Walston. After his Broadway success, he was cast in larger feature roles in movies. In 1960, Redford was cast as Danny Tilford, a mentally disturbed young man trapped in the wreckage of his family garage, in "Breakdown", one of the last episodes of the syndicated adventure series Rescue 8, starring Jim Davis and Lang Jeffries.[20] Redford earned an Emmy nomination as Best Supporting Actor for his performance in The Voice of Charlie Pont (ABC, 1962). One of his last television appearances until 2019 was on October 7, 1963, on Breaking Point, an ABC medical drama about psychiatry.[4]

In 1962, Redford received his second film role in War Hunt,[21] and was cast soon after alongside screen legend Alec Guinness in the war comedy Situation Hopeless... But Not Serious, in which he played a U.S. soldier falsely imprisoned by a German civilian even after the war had ended. In Inside Daisy Clover (1965), which won him a Golden Globe for best new star, he played a bisexual movie star who marries starlet Natalie Wood, and rejoined her along with Charles Bronson for Sydney Pollack's This Property Is Condemned (1966)—again, as her lover, though this time in a film which achieved even greater success. The same year saw his first teaming (on equal footing) with Jane Fonda, in Arthur Penn's The Chase. The film marked the only time Redford starred with Marlon Brando.[22]

1967–1979: Career stardom

Fonda and Redford were paired again in the popular big-screen version of Barefoot in the Park (1967)[3] and were again co-stars a dozen years later in Pollack's The Electric Horseman (1979), followed 38 years later with a Netflix feature, Our Souls at Night. After this initial success, Redford became concerned about his blond male stereotype image[23] and refused roles in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Graduate.[24] Redford found the niche he was seeking in George Roy Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), scripted by William Goldman, in which he was paired for the first time with Paul Newman. The film was a huge success and made him a major bankable star,[3] cementing his screen image as an intelligent, reliable, sometimes sardonic good guy.[25]

While Redford did not receive an Academy Award or Golden Globe nomination for playing the Sundance Kid, he won a British Academy of Film and Television Award (BAFTA) for that role and his parts in Downhill Racer[26] (1969) and Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969). The latter two films and the subsequent Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1970), and The Hot Rock (1972) were not commercially successful. Redford had long harbored ambitions to work on both sides of the camera. As early as 1969, Redford had served as the executive producer for Downhill Racer.[3] The political satire The Candidate (1972) was a moderate box-office and critical success.[27]

Starting in 1973, Redford experienced an almost unparalleled four-year run of box-office successes. The western Jeremiah Johnson's (1972) box-office earnings from early 1973 until its second re-release in 1975 would have placed it as the 2nd-highest-grossing film of 1973.[28] His romantic period drama with Barbra Streisand, The Way We Were (1973), was the 5th-highest-grossing film of 1973.[28] The crime caper reunion with Paul Newman, The Sting (1973), became the top-grossing film of 1974[29] and one of the top-twenty highest-grossing movies of all time when adjusted for inflation, and it also landed Redford the lone nomination of his career for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[3] The following year he starred in the romantic drama The Great Gatsby (1974), also starring Mia Farrow, Sam Waterston, and Bruce Dern. The film was the 8th-highest-grossing film of 1974.[29] Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) placed as the 10th-highest-grossing film for 1974, as it was re-released due to the popularity of The Sting.[29] In 1974, Redford became the first performer since Bing Crosby in 1946 to have three films in a year's top-ten-grossing titles. Each year between 1974 and 1976, movie exhibitors voted Redford Hollywood's top box-office star.[3]

In 1975, Redford's hit movies included a 1920s aviation drama, The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), and the spy thriller Three Days of the Condor (1975), alongside Faye Dunaway, which finished 16th and 17th in box-office grosses for 1975, respectively.[30] In 1976, he co-starred with Dustin Hoffman in the 2nd-highest-grossing film for the year, the critically acclaimed All the President's Men.[31] In 1976, Redford published The Outlaw Trail: A Journey Through Time. Redford stated, "The Outlaw Trail. It was a name that fascinated me—a geographical anchor in Western folklore. Whether real or imagined, it was a name that, for me, held a kind of magic, a freedom, a mystery. I wanted to see it in much the same way as the outlaws did, by horse and by foot, and document the adventure with text and photographs."[32]

All the President's Men, in which Redford and Hoffman play Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, was a landmark film for Redford. Not only was he the executive producer and co-star, but the film's serious subject matter—the Watergate scandal—and its attempt to create a realistic portrayal of journalism also reflected the actor's offscreen concerns for political causes.[3] The film landed eight Academy Award nominations, including for Best Picture and Best Director (Alan J. Pakula), while winning for the Best Screenplay (Goldman). It won the New York Film Critics Award for Best Picture and Best Director. In 1977, Redford appeared in a segment of the war film A Bridge Too Far (1977). He took a two-year hiatus from movies before starring as a past-his-prime rodeo star in the adventure-romance The Electric Horseman (1979). This film reunited him with Fonda, finishing at No. 9 at the box office in 1980.[33]

1980–1998: Directorial debut

Redford's first film as director was the drama film Ordinary People (1980), a drama about the slow disintegration of an upper-middle class family after the death of a son. Redford was credited with obtaining a powerful, dramatic performance from Mary Tyler Moore, as well as superb work from Donald Sutherland and Timothy Hutton, who also won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. The film is one of the most critically and publicly acclaimed films of the decade, winning four Academy Awards, including Best Director for Redford himself, and Best Picture.[34][3] Critic Roger Ebert declared it "an intelligent, perceptive, and deeply moving film."[35] Later that year he appeared in the prison drama Brubaker (1980), playing a prison warden attempting to reform the system.[36]

Soon afterwards, he starred in the baseball drama The Natural (1984).[3] Sydney Pollack's Out of Africa (1985), with Redford in the male lead role opposite Meryl Streep, became a large box office success (combined 1985 and 1986 grosses placed it at No. 5 for 1986),[37] won a Golden Globe for Best Picture,[38] and won seven Oscars, including Best Picture. Streep was nominated for Best Actress, but Redford did not receive a nomination. The movie proved to be Redford's biggest success of the decade and Redford and Pollack's most successful of their seven movies together.[3] Redford's next film, Legal Eagles (1986) alongside Debra Winger, was only a minor success at the box office.[39]

Redford did not direct again until The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), a well-crafted, though not commercially successful, screen version of John Nichols's acclaimed novel of the Southwest. The Milagro Beanfield War is the story of the people of Milagro, New Mexico (based on the real town of Truchas in northern New Mexico), overcoming big developers who set about to ruin their community and force them out with tax increases.

Redford continued as a major star throughout the 1990s and 2000s. In 1992, he released his third film as a director, the period drama A River Runs Through It, based on Norman Maclean's novella, starring Craig Sheffer, Brad Pitt, and Tom Skerritt. Redford received a nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Director. This was a return to mainstream success for Redford as a director and brought a young Pitt to greater prominence. In 1994, he directed the exposé Quiz Show about the quiz show scandal of the late 1950s.[3] In the latter film, Redford worked from a screenplay by Paul Attanasio with cinematographer Michael Ballhaus and a cast that featured Paul Scofield, John Turturro, Rob Morrow, and Ralph Fiennes. David Ansen of Newsweek wrote, "Robert Redford may have become a more complacent movie star in the last decade, but he has become a more daring and accomplished filmmaker. 'Quiz Show' is his best movie since 'Ordinary People'".[40]

In 1993, he starred in Indecent Proposal as a billionaire businessman who tests a couple's morals; the film became one of the year's biggest hits. He co-starred with Michelle Pfeiffer in the newsroom romance Up Close & Personal (1996),[41] and with Kristin Scott Thomas and a young Scarlett Johansson in The Horse Whisperer (1998), which he also directed.[3] Redford also continued work in films with political contexts, such as Havana (1990), playing Jack Weil, a professional gambler in 1959 Cuba during the Revolution, as well as Sneakers (1992), in which he co-starred with River Phoenix and Sidney Poitier.[42]

1999–2012: Expansive filmmaking and later works

Redford also directed Matt Damon and Will Smith in The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000).[43] He appeared as a disgraced Army general sent to prison in the prison drama The Last Castle (2001), directed by Rod Lurie.[44] In the same year, Redford reteamed with Pitt for Spy Game, another success for the pair but with Redford switching this time from director to actor. During that time, he planned to direct and star in a sequel of The Candidate[45] but the project never happened.[46] Redford, a leading environmental activist, narrated the IMAX documentary Sacred Planet (2004), a sweeping journey across the globe to some of its most exotic and endangered places.[47] In The Clearing (2004), Redford portrayed Wayne Hayes, a shrewd businessman whose kidnapping forces him and his wife to confront the personal compromises behind their seemingly ideal life.[48]

Redford stepped back into producing with The Motorcycle Diaries (2004), a coming-of-age road film about a young medical student, Ernesto "Che" Guevara, and his friend Alberto Granado. It also explored the political and social issues of South America that influenced Guevara and shaped his future. With five years spent on the film's making, Redford was credited by director Walter Salles for being instrumental in getting it made and released.[49] Back in front of the camera, Redford received good notices for his role in director Lasse Hallström's An Unfinished Life (2005) as a cantankerous rancher who takes in his estranged daughter-in-law (Jennifer Lopez) and the granddaughter he never knew, after they flee an abusive relationship.[50]

Meanwhile, Redford returned to familiar territory when he reteamed with Streep, 22 years after they starred in Out of Africa, for his personal project Lions for Lambs (2007), which also starred Tom Cruise. After a great deal of hype, the film opened to mixed reviews and disappointing box office. Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote, "Lions for Lambs is so square it's like something out of the gray twilight glow of the golden age of television. Even the military plot, which clunks, seems to be taking place on stage."[51] In 2010, Redford released The Conspirator, a period drama revolving around the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.[52] Redford appeared in the 2011 documentary Buck by Cindy Meehl, where he discussed his experiences with title subject Buck Brannaman during the production of The Horse Whisperer.[53] In 2012, Redford directed The Company You Keep, in which he starred as a former Weather Underground activist who goes on the run after a journalist discovers his identity. The film starred himself, Shia LaBeouf, and Julie Christie.[54]

2013–2025: Final roles and retirement

In 2013, Redford starred in All Is Lost, directed by J.C. Chandor, about a man lost at sea. He received acclaim for his performance in the film, in which he was its only cast member, and there is almost no dialogue. Redford was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama and won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor, his first time winning an acting honor from that group (he had been nominated in 1969 for Downhill Racer). Ali Arikan wrote in RogerEbert.com, "Chandor plays to Redford's strengths: his battered visage, calm determination, and detachment from the vagaries of a "normal" existence. In return, Redford gives the performance of the latter half of his career in a role that is not just physically, but also psychologically demanding".[55]

In April 2014, Redford played the main antagonist of the Marvel Studios superhero film Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Alexander Pierce, the head of S.H.I.E.L.D. and leader of the Hydra cell operating the Triskelion.[56] Redford was a co-producer and, with Emma Thompson and Nick Nolte, acted in the film A Walk in the Woods (2015), based on Bill Bryson's book of the same name. Redford had optioned the film rights for the book from Bryson after reading it more than a decade earlier, with the intent of co-starring in it with Paul Newman, but had shelved the project after Newman's death.[57]

Also in 2015, he played news anchor Dan Rather in James Vanderbilt's Truth alongside Cate Blanchett. The film received mixed reviews with Justin Chang of Variety noting, "Redford, who bears a solid resemblance to Rather but not quite enough to make you forget whom you're watching, plays the veteran newsman with easy gravitas, inner strength and a gentle paternal twinkle, with little display of the anger and volatility for which he was often known over the course of his storied career."[58] In 2016, he took the supporting role of Mr. Meacham in the Disney remake Pete's Dragon. The next year, Redford starred in The Discovery and Our Souls at Night, both released on Netflix streaming in 2017. The latter film, which he also produced, reunited him with Fonda for the fifth time and garnered positive reviews.[59]

Redford played bank robber Forrest Tucker in the David Lowery–directed drama film The Old Man & the Gun, which was released in September 2018, and for which he received a Golden Globe nomination. Alissa Wikinson wrote in Vox, "In The Old Man & the Gun, both Redford and Lowery are returning to their roots. For Redford, a role as a lifelong bank robber feels like a fitting cap to a career effectively launched half a century ago with his role alongside Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid."[60] In August 2018, Redford announced his retirement from acting after completion of the film,[61][62] though the following month, Redford stated that he "regretted" announcing his retirement because "you never know".[63]

Redford briefly reprised his role as Alexander Pierce with a cameo in Avengers: Endgame, filmed in 2017 before the completion of the former film.[64] Redford, an executive producer of the series Dark Winds, made a cameo alongside fellow executive producer George R. R. Martin portraying a detainee playing chess.[65]

Filmography and accolades

In his directing debut, Redford won the 1980 Academy Award for Best Director for the film Ordinary People. He was a 2002 Academy Honorary Award recipient at the 74th Academy Awards.[66] In 2017, he was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 74th Venice Film Festival.[67] On February 22, 2019, Redford received the Honorary César at the 44th César Awards in Paris.[68]

Redford attended the University of Colorado in the 1950s and received an honorary degree in 1988. In 1989, the National Audubon Society awarded Redford its highest honor, the Audubon Medal.[69] In 1995, he received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Bard College. Redford received an honorary doctorate from Brown University in 2008.[70] He was a 2010 recipient of the New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts.[71] In 2014, Redford was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world.[72] In May 2015, Redford delivered the commencement address and received an honorary degree from Colby College in Maine.[73]

In 1996, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton.[74] On October 14, 2010, Redford was appointed chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by President Nicolas Sarkozy.[75] On November 22, 2016, President Barack Obama honored Redford with a Presidential Medal of Freedom.[76] In December 2005, he received the Kennedy Center Honors for his contributions to American culture. The honors recipients are recognized for their lifetime contributions to American culture through the performing arts: whether in dance, music, theater, opera, motion pictures, or television.[77]

In 2008, Redford received The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, one of the richest prizes in the arts, given annually to "a man or woman who has made an outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankind's enjoyment and understanding of life."[78] The University of Southern California (USC) School of Dramatic Arts announced the first annual Robert Redford Award for Engaged Artists in 2009. According to the school's website, the award was created "to honor those who have distinguished themselves not only in the exemplary quality, skill and innovation of their work, but also in their public commitment to social responsibility, to increasing awareness of global issues and events, and to inspiring and empowering young people."[79]

Other ventures

Sundance Film Festival

With the financial proceeds of his acting success, starting with his salaries from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Downhill Racer, Redford bought a ski area on the east side of Mount Timpanogos, located in the Wasatch Mountains[80] northeast of Provo, Utah, called "Timp Haven".[81][82] He renamed it "Sundance" after his Sundance Kid character.[3] Redford's ex-wife Lola was from Utah and they had built a home in the area in 1963. Portions of the movie Jeremiah Johnson (1972), a film which was both one of Redford's favorites and one that heavily influenced him, were shot near the ski area.[83] Redford went on to create the Sundance Film Festival, which became the country's largest festival for independent films. The festival, which was initially known as the Utah/US festival, eventually would be named for Redford's "Sundance" land.[80] In 2008, Sundance exhibited 125 feature-length films from 34 countries, with more than 50,000 attendees in Salt Lake City[84][85] and Park City, Utah.[86] Robert Redford also founded the Sundance Institute, Sundance Cinemas, Sundance Catalog, and the Sundance Channel, all in and around Park City, 30 miles (48 km) north of the Sundance ski area.[3] Redford also owned a Park City restaurant, Zoom, that closed in May 2017.[87]

Production companies

Redford was the co-owner of Wildwood Enterprises, Inc., with Bill Holderman, producer, with the following film credits: Lions for Lambs; Quiz Show; A River Runs Through It; Ordinary People; The Horse Whisperer; The Legend of Bagger Vance; Slums of Beverly Hills; The Motorcycle Diaries; and The Conspirator.[88]

Redford was the president and co-founder of Sundance Productions, with Laura Michalchyshyn.[89] Sundance Productions produced Chicagoland (CNN), Cathedrals of Culture (Berlin Film Festival), The March (PBS) and Emmy nominee All The President's Men Revisited (Discovery), Isabella Rossellini's Green Porno Live!, and To Russia With Love on Epix.[90]

Following his founding of the nonprofit Sundance Institute in Park City, Utah, in 1981, Redford was deeply involved with independent film.[3] Through its various workshop programs and popular film festival, Sundance has provided support for independent filmmakers. In 1995, Redford signed a deal with Showtime to start a 24-hour cable television channel devoted to airing independent films. The Sundance Channel premiered on February 29, 1996.[91]

Personal life

Marriage and family

On August 9, 1958, Redford married Lola Van Wagenen in Las Vegas.[4][page needed] The couple had four children: Scott Anthony, Shauna Jean, David James, and Amy Hart. Scott died of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) at the age of 2½ months. Shauna is a painter and married to journalist Eric Schlosser.[92] James was a writer and producer, and died in 2020.[93] Amy is an actress, director, and producer.[94] Redford had seven grandchildren.[95][96]

Redford and Van Wagenen never publicly announced a separation or divorce, but in 1982, entertainment columnist Shirley Eder reported that the pair "have been very much apart for several years."[97] In 1991, Parade magazine said, "it is unclear whether the divorce has been finalized."[98]

That divorce became official at some point because, on July 11, 2009, Redford and his longtime girlfriend, Sibylle Szaggars,[99] married at the Louis C. Jacob Hotel in Hamburg, Germany. She had moved in with Redford in 1996 and shared his home in Sundance, Utah.[100] In May 2011, Robert Redford: The Biography was published by Alfred A. Knopf, written by Michael Feeney Callan with Redford's cooperation, drawing extensively from his personal papers, diaries, and taped interviews.[4][page needed]

Although Redford primarily resided at the Sundance Resort in Utah, he owned a house in Tiburon, California, which was sold in 2024. He also had a property in Santa Fe, New Mexico.[101]

Political activism

Redford supported environmentalism, Native American rights, LGBT rights,[102] and the arts. He was a supporter of advocacy groups like the Political Action Committee of the Directors Guild of America.[103] He was the executive producer and narrator of the documentary film Incident at Oglala, about American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier.[104]

Redford supported Brent Cornell Morris in his unsuccessful campaign for the Republican nomination for Utah's 3rd congressional district in 1990.[103] Redford also supported Gary Herbert, another Republican and a friend, in Herbert's successful 2004 campaign to be elected lieutenant governor of Utah. Herbert later became governor of Utah.[105]

As an avid environmentalist, Redford was a trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council. He endorsed Democratic president Barack Obama for re-election in 2012.[106] Redford was the first quote on the back cover of Donald Trump's book Crippled America (2015), saying of Trump's candidacy, "I'm glad he's in there, being the way he is, and saying what he says and the ways he says it, I think shakes things up and I think that is very needed."[107][108][page needed] A representative later clarified that Redford's statement, taken from a longer conversation with Larry King, was not intended to endorse Trump for president.[109]

In 2019, Redford penned an op-ed in which he referred to Trump's administration as a "monarchy in disguise" and stated "[i]t's time for Trump to go".[110] Redford later co-authored another op-ed in which he criticized Trump's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic while also citing the collective public response to the pandemic as a model for how to respond to climate change.[111] He criticized the decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.[112] In July 2020, Redford penned an op-ed in which he stated that President Trump lacks a "moral compass". In the same piece, he announced that he would be supporting Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election.[113]

Redford was opposed to the TransCanada Corporation's Keystone Pipeline.[114] In 2013, he was identified by its CEO, Russ Girling, for leading the anti-pipeline protest movement.[114] In April 2014, Redford, a Pitzer College Trustee, and Pitzer College President Laura Skandera Trombley announced that the college would divest fossil fuel stocks from its endowment; at the time, it was the higher-education institution with the largest endowment in the U.S. to make this commitment. The press conference was held at the LA Press Club. In November 2012, Pitzer launched the Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability at Pitzer College.[115]

Death and tributes

On September 16, 2025, Redford died in his sleep at his home in Sundance, Utah, at the age of 89.[19][116] Several of Redford's co-stars paid tribute to him, including frequent collaborator Jane Fonda, who wrote, "He meant a lot to me and was a beautiful person in every way. He stood for an America that we have to keep fighting for."[117] His Out of Africa co-star Meryl Streep wrote, "One of the lions has passed. Rest in peace, my lovely friend." His The Way We Were co-star Barbra Streisand released a lengthy statement, which read in part, "Bob was charismatic, intelligent, intense, always interesting—and one of the finest actors ever."[118] His All the President's Men co-star Dustin Hoffman paid tribute to Redford, writing, "Working with Redford...was one of the greatest experiences I've ever had...I'll miss him".[119] Journalist Bob Woodward, whom Redford portrayed in All the President's Men, also paid tribute.[120]

Others who commented on Redford's death include politicians such as U.S. President Donald Trump, former president Barack Obama, the former first lady Hillary Clinton and former Vice President Al Gore.[121] Numerous prominent figures from the entertainment industry paid tribute to Redford, including filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese and Ron Howard and actors such as Morgan Freeman, Leonardo DiCaprio, Alec Baldwin, Scarlett Johansson, Mark Ruffalo, Julianne Moore, Edward Norton, Josh Brolin, Ethan Hawke, and Antonio Banderas.[122][123][93][124][125][126]

Redford is set to be interred on his Sundance property following a low-key funeral.[127]

Legacy and reception

During his career, Redford was often described as a sex symbol, particularly during the 1970s.[128] The BBC News called his appeal "all-American good looks [that] couldn't be ignored".[129] The Associated Press noted that Redford's "wavy blond hair and boyish grin made him the most desired of leading men" during the height of his career.[128] However, Redford himself rejected the label of being a sex symbol. In a 1974 interview with The New York Times, Redford responded to his image as a symbol by saying "I never thought of myself as a glamorous guy, a handsome guy, any of that stuff. Suddenly, there's this image...Glamour image can be a real handicap. It is crap."[130]

Following Redford's death, an obituary published in Variety remarked that he "became a godfather for independent film as founder of the Sundance Film Institute", that "as a movie star in his prime, few could touch him" and that "in his '70s heyday, few actors possessed Redford's star wattage".[21] Writing for The Guardian, Andrew Pulver characterized Redford as a "giant of American cinema" and "one of the defining movie stars of the 1970s, crossing with ease between the Hollywood New Wave and the mainstream film industry".[131] The Los Angeles Times remembered Redford as a "generational icon".[49] In France, Culture Minister Rachida Dati praised him as "a giant of American cinema".[132] As the founder of Sundance Film Festival, he has been described as a “godfather of independent cinema”.[133]

The New York Times noted that Redford's films were known for depicting serious topics such as corruption and grief that "[resonated] with the masses", as he wanted his films to carry "cultural weight", and that Redford took "risks by exploring dark and challenging material".[19] He was hailed as one of "few truly iconic screen figures of the past half-century" and as "Hollywood's Golden Boy" by The Hollywood Reporter.[134] Filmmaker Ron Howard praised Redford and his work, calling him "a tremendously influential cultural figure" and an "artistic gamechanger".[135] His creation of the Sundance Film Festival was credited as a "boost [to] independent film-making".[135] After he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016, The Salt Lake Tribune called Redford's Sundance Film Festival a "catalyst for an explosion of independent films".[136]

Time noted Redford's environmental activism, calling him "fiercely dedicated to pushing for a world that was habitable for all" and mentioning that the Redford Foundation helped support environmentally friendly filmmaking.[137] His environmental awareness led to Fox News remembering Redford as a "Hollywood icon" [who] "committed himself to being a good steward of the environmental movement and a champion of the American Southwest".[138] In 2016, then-president Barack Obama called Redford "one of the foremost conservationists of our generation".[139]

References

Citations

- "Monitor". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1220/1221. August 17–24, 2012. p. 28.

- Schlosser, Conor (November 8, 2024). "Keeping Nature in the Picture: An Interview with Robert Redford". Orion. Archived from the original on February 23, 2025. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- Lipton, James; et al. (January 30, 2005). Inside the Actors Studio: Robert Redford (Television episode). Inside the Actors Studio.

- Callan 2011.

- Farber, Stephen (October 20, 1991). "Sponsored Archives: A Robert Redford Retrospective, Redford Turns West Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- "New England Historic Genealogical Society". Archived from the original on December 12, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2008.. Web.archive.org (December 12, 2005). Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- "Redford discusses how Texas saved itself from serious environmental harm". Chron. March 23, 2008. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- Cronin, Brian (July 14, 2011). "Did Robert Redford play high school baseball with Don Drysdale?". Los Angeles Times. (blog). Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- "Polio battle sparked Redford's Jonas doco". Special Broadcasting Service. Australian Associated Press. February 13, 2014. Archived from the original on December 15, 2024. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- "Robert Redford". Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- De Forest, Ben (August 10, 1983). "Redford plays a natural". The Dispatch. (Lexington, North Carolina). Associated Press. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Redford visits 'party school'". Wilmington Morning Star. (North Carolina). Associated Press. May 14, 1987. p. 7D. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Entertainment/Media". Kappa Sigma Fraternity. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014.

- "Entra". Flickr.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- Robertson, Nan (October 4, 1984). "Academy of Dramatic Arts at 100". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- Casper 2011, p. xlv.

- "Watch: For Robert Redford's first role ever, he took a punch on Maverick". Me-TV Network. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- "Chris Hicks: Robert Redford cut his teeth on '60s TV". Deseret News. August 23, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Barnes, Brooks (September 16, 2025). "Robert Redford, Screen Idol Turned Director and Activist, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Breakdown, Rescue 8, March 31, 1960, retrieved August 9, 2022

- "Robert Redford, 'Butch Cassidy' and 'All the President's Men' Icon, Dies at 89". Variety. September 16, 2025. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Robert Redford, Hollywood legend indelibly linked to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting". Yahoo. September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Gritten, David (August 27, 2004). "Robert Redford acts his age". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Kubincanek, Emily (September 24, 2018). "A Beginner's Guide to Robert Redford". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- "Robert Redford's Career Highlights". femalefirst.co.uk. December 22, 2013. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Ebert, Roger (June 15, 1969). "Interview With Robert Redford". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- "'The Candidate': THR's 1972 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. June 29, 2018. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 305.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 315.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 321.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 328.

- Redford, Robert (1976). The Outlaw Trail: A Journey Through Time. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 8–13. ISBN 0448145901.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 355.

- Harmetz, Aljean (April 1981). "'Ordinary People' Wins The Academy Award For Best". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "Ordinary People movie review". Roger Ebert.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "Brubaker movie review". Roger Ebert.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Michael Gebert, The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, St. Martin's Paperbacks, New York, 1996, p. 401.

- Earls, John (January 10, 2019). "'Bohemian Rhapsody' is the worst-reviewed Golden Globes winner in 33 years". NME. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Film: Ivan Reitman's 'Legal Eagles'". The New York Times. June 18, 1986. Archived from the original on January 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Ansen, David (September 18, 1994). "When America Lost Its Innocence – Maybe". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "Up Close and Personal". The New York Times. March 1, 1996. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Cryer, Vanessa (December 19, 2021). "Sneakers: Robert Redford and River Phoenix nerd out in 1992's prescient, high-tech caper". Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- Scott, A.O. (November 3, 2000). "Film Review; Golf Angel to the Rescue". The New York Times. p. E1. Archived from the original on December 22, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Mitchell, Elvis (October 19, 2001). "Film Review; Manning the Ramparts for Old Glory". The New York Times. p. E16. Archived from the original on December 1, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Susman, Gary (October 24, 2002). "Robert Redford plans Candidate sequel". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- Garber, Megan (September 29, 2016). "The Candidate and the Sequel That Never Was". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- Holden, Stephen (April 22, 2004). "Film Review; Now, It Isn't Nice to Foul Mother Nature". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- McCarthy, Todd (June 25, 2004). "The Clearing". Variety. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Saad, Nardine (September 16, 2025). "Robert Redford, Oscar-winning generational icon who founded the Sundance Institute, dies at 89". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- McCarthy, Todd (September 13, 2004). "An Unfinished Life". Variety. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Gleiberman, Owen (November 7, 2007). "Lions for Lambs". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "History's Loose Ends, and a Tightening Noose". The New York Times. April 15, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Carr, David (June 12, 2011). "You Can Also Lead a Horse to Nirvana". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Holden, Stephen (April 5, 2013). "Remembering the Side of the '60s That Wasn't All Peace and Love". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "All is Lost movie review & film summary". Rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "Robert Redford Confirms Captain America: The Winter Soldier Role". Yahoo! News. April 3, 2013. Archived from the original on May 4, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- Gajewski, Ryan (September 2, 2015). "'A Walk in the Woods' Director on Why Robert Redford Put Film on Shelf After Paul Newman's Death". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- "Toronto Film Review: 'Truth'". Variety. September 13, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- Our Souls at Night (2017), vol. Rotten Tomatoes, archived from the original on November 27, 2017, retrieved December 30, 2018,

- "Robert Redford bids farewell to the silver screen in the pitch-perfect The Old Man & the Gun". Vox. September 25, 2018. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- "Exclusive: Robert Redford announces he's retiring from acting". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Pulver, Andrew (August 6, 2018). "Robert Redford confirms retirement from acting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "Robert Redford Reveals He Never Should Have Said He Is Retiring: 'That Was a Mistake'". People. September 21, 2018. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- Means, Sean P. (April 30, 2019). "Robert Redford comes out of retirement for a strategic cameo in (spoiler alert!) 'Avengers: Endgame'". Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on April 24, 2025. Retrieved May 5, 2025.

- Chaney, Jen (March 9, 2025). "How Dark Winds Scored Two Legends for a Premiere Cameo". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 3, 2025. Retrieved May 5, 2025.

- "Nominees & Winners for the 74th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014.

- "Biennale Cinema 2017 | Jane Fonda and Robert Redford Golden Lions in Venice". La Biennale di Venezia. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- "Robert Redford Gets Honorary French 'Oscar'". Radio France Internationale. February 23, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Previous Audubon Medal Awardees". January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- "Brown University to Confer Seven Honorary Degrees May 25" (Press release). Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- "Award Winners". New Mexico Museum of Art. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Gibbs, Nancy. "Editor's Letter: The Ties That Bind the TIME 100". Time. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- "Robert Redford". Commencement. May 24, 2015. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- "Lifetime Honors: National Medal of Arts". nea.gov. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- "SUNfiltered | Robert Redford Receives "Legion d'Honneur" from France's President Sarkozy". sundancechannel.com. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- "President Obama Names Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". whitehouse.gov. November 16, 2016. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2016 – via National Archives.

- Files, John (December 5, 2005). "At Kennedy Center Honors, 5 More Join an Elite Circle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- "The Prize". The Dorothy & Lillian Gish Prize. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- "Robert Redford Award for Engaged Artists". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Smart, Jack (September 16, 2025). "How Robert Redford Changed Movies with the Sundance Film Festival: 'I've Devoted So Much of My Life to It'". People. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Exclusive: Robert Redford sells Sundance Mountain Resort to pair of high-end resort firms". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved July 22, 2025.

- "Robert Redford selling Sundance Mountain Resort; 300 acres to be preserved". Deseret News. December 12, 2020. Archived from the original on June 1, 2025. Retrieved July 22, 2025.

- "Where Was Jeremiah Johnson Filmed?". The Cinemaholic. February 17, 2021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Benedict, Patrick (March 28, 2025). "Robert Redford comments on Sundance Film Festival's move to Boulder | Gephardt Daily". Gephardt Daily. Archived from the original on June 22, 2025. Retrieved July 22, 2025.

- Moss, Linda (July 21, 2025). "Robert Redford-founded Sundance Living to shutter its stores".

- Papp, Adrienne. "2008 Sundance Insider" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Gardner, Chris (November 10, 2016). "Robert Redford's Park City Restaurant Zoom to Close Its Doors". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- "Wildwood Enterprises, Inc.—Production Company—Backstage". backstage.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- "Watergate Reporting, the Second Draft". The New York Times. April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Who We Are—Sundance Productions". sundance-productions.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- Kim, Gobi (January 1, 1998). "Programming Profile: The Sundance Channel—And the Festival Goes on... TV". Realscreen.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- Fox, Courtney (February 12, 2021). "Robert Redford: Meet The Hollywood Legend's Four Children". Wide Open Country. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Robert Redford, movie star and Sundance founder, dies at 89". The Washington Post. September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Villas, Myra (March 6, 2016). "In Development: A Chat with Director Amy Redford". Villanova ICE Institute. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- "Robert Redford praises younger wife Sibylle Szaggars, talks retirement". ABC7 Los Angeles. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Braun, Kelly (August 18, 2022). "Robert Redford's Family: Get to Know Kids James, Shauna, Amy and Scott". Closer Weekly. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- Eder, Shirley (October 7, 1982). "Redfords have been living apart for a long time". Detroit Free Press. p. 13B.

- "Walter Scott's Personality Parade." The Salt Lake Tribune. July 21, 1991.

- "Sibylle Redford". Art.State.gov. United States Department of State. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- "Robert Redford marries long-term girlfriend". The Daily Telegraph. London. July 15, 2009. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- "Robert Redford, 88, selling another California home to spend more time out of state". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Robert Redford stands up for equal rights at Equality Utah Allies dinner". Dot429. September 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- "Robert Redford's Federal campaign contributions". Newsmeat.com. Archived from the original on October 2, 2007.

- Peter Travers (June 26, 1992). "Incident at Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 15, 2024. Retrieved September 18, 2025.

- "Robert Redford honored by Utah's leaders". Politico. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- Redford, Robert (October 19, 2012). "Why I'm Supporting President Obama". HuffPost. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- Garland, Eric (September 2, 2015). "Robert Redford 'glad' Trump is running". Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- Trump 2015.

- "Robert Redford Denies Endorsing Donald Trump for President". The Hollywood Reporter. September 8, 2015. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Redford, Robert (November 26, 2019). "Robert Redford: President Trump's dictator-like administration is attacking the values America holds dear". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Redford, Robert; Redford, James (April 30, 2020). "Trump's coronavirus failures offer warnings and lessons about future climate change challenges". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Redford, Robert (November 8, 2019). "Robert Redford: A race against time to undo damage caused by Trump". CNN. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Redford, Robert (July 7, 2020). "Robert Redford: This is who gets my vote in 2020". CNN. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- "Robert Redford helping anti-pipeline cause, says TransCanada head". CBC News. November 30, 2013. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- "Pitzer College". Office of Communications. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- "Redford died in the mountains of Utah, surrounded by those he loved—publicist". BBC News. September 16, 2025. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

Robert Redford's publicist Cindi Berger says the actor died earlier today at his home 'at Sundance in the mountains of Utah—the place he loved, surrounded by those he loved.'

- Badshah, Nadeem; Bakare, Lanre. "Robert Redford dies: Meryl Streep leads tributes to giant of American cinema, saying 'one of the lions has passed' – latest updates". The Guardian. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Barbra Streisand Pays Tribute to Robert Redford and the 'Pure Joy' of Making 'The Way We Were' Together: 'One of the Finest Actors Ever'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Dustin Hoffman, Demi Moore, Barbra Streisand and more remember Robert Redford after his death". ABC News. Retrieved September 19, 2025.

- "Bob Woodward Honors Robert Redford: 'A Noble and Principled Force for Good'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 19, 2025.

- Johnson, Ted (September 17, 2025). "Robert Redford's Activism Influenced The Environmental Movement, But He Pursued Politics His Own Way". Deadline. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- "Meryl Streep Honors Robert Redford: 'One Of The Lions Has Passed'; Hollywood Tributes Pour In". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "'A Genius Has Passed': Tributes Pour in for Robert Redford After His Death". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Robert Redford Death: Marvel, DCU Remember Oscar-Winning Actor – Russo Bros, James Gunn's Emotional Posts For 'THE Movie Star'". Times Now. September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Jane Fonda, Barbra Streisand, Martin Scorsese, Morgan Freeman Pay Tribute to Robert Redford: 'He Stood for an America We Have to Keep Fighting for'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- "Scarlett Johansson reacts to death of Horse Whisperer costar Robert Redford: 'Bob taught me what acting could be'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 17, 2025. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- Javed, Maliha (September 18, 2025). "Robert Redford's final wish laid bare". www.geo.tv.

- "Robert Redford, Oscar-winning director, actor and indie patriarch, dies at 89". AP. September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- "Robert Redford: The enthralling star whose 'aura' lit up Hollywood". BBC News. September 17, 2025. Retrieved September 17, 2025 – via MSN.

- "When Robert Redford opened up about being a reluctant sex symbol: 'Glamour image can be a real handicap. It is crap'". The Hindustan Times. September 17, 2025. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- Pulver, Andrew (September 16, 2025). "Robert Redford, giant of American cinema, dies aged 89". The Guardian.

- "Un lion s'en est allé : Meryl Streep, Donald Trump, Stephen King... réagissent après le décès de Robert Redford" (in French). Le Figaro. September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- https://uk.news.yahoo.com/robert-redford-oscar-winner-godfather-130552432.html

- "Robert Redford, Golden Boy of Hollywood, Dies at 89". The Hollywood Reporter. September 16, 2025. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Acting legend Robert Redford dies aged 89". BBC. September 16, 2025. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "President Obama honors Robert Redford with America's top civilian award". The Salt Lake City Tribune. November 25, 2016. Archived from the original on December 11, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "What Working On An Oil Field Taught Robert Redford About Climate Change". Time. September 16, 2025. Archived from the original on September 18, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- Speck, Emilee (September 16, 2025). "Robert Redford remembered as climate activist, steward of American Southwest". Fox News. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- "Remarks by the President at Presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". Obama White House. November 22, 2016. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

Works cited

- Callan, Michael Feeney (2011). Robert Redford: The Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-45055-9.

- Casper, Drew (March 1, 2011). Hollywood Film 1963-1976: Years of Revolution and Reaction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9523-5.

- Trump, Donald J. (November 3, 2015). Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again. Threshold Editions. ISBN 978-1-5011-3796-9.

Further reading

- Meyerson, Debra E.; Fryer, Bronwyn (May 1, 2002). "Turning an Industry Inside Out: A Conversation with Robert Redford". Harvard Business Review.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Robert Redford, the big-screen charmer turned Oscar-winning director whose hit movies often helped America make sense of itself and who, offscreen, evangelized for environmental causes and fostered the Sundance-centered independent film movement, died early Tuesday morning at his home in Utah. He was 89.

His death, in the mountains outside Provo, was announced in a statement by Cindi Berger, the chief executive of the publicity firm Rogers & Cowan PMK. She said he had died in his sleep but did not provide a specific cause. He was in “the place he loved surrounded by those he loved,” the statement said.

With a distaste for Hollywood’s dumb-it-down approach to moviemaking, Mr. Redford typically demanded that his films carry cultural weight, in many cases making serious topics like grief (familial, societal) and political corruption resonate with audiences, in no small part because of his immense star power. Unlike other stars of his caliber, he took risks by exploring dark and challenging material; while some people might only have seen him as a sun-kissed matinee god, his filmography — like his personal life — contained currents of tragedy and sadness.

As an actor, his biggest films included “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), with its loving look at rogues in a dying Old West, and “All the President’s Men” (1976), about the journalistic pursuit of President Richard M. Nixon in the Watergate era. (Mr. Redford played Bob Woodward and used his clout in Hollywood to bring the book of the same name, by Mr. Woodward and Carl Bernstein, to the screen.) In “Three Days of the Condor” (1975) Mr. Redford was an introverted C.I.A. analyst caught in a murderous cat-and-mouse game. “The Sting” (1973), about Depression-era grifters, gave Mr. Redford his first and only Oscar nomination as an actor.

Advertisement

Mr. Redford was one of Hollywood’s preferred leads for decades, whether in comedies, dramas or thrillers; he had range. Studios often sold him as a sex symbol. Although he was a subtle performer with a definite magnetism, his body of work as a romantic leading man owed a great deal to the commanding actresses who were paired with him — Jane Fonda in “Barefoot in the Park” (1967), Barbra Streisand in “The Way We Were” (1973), Meryl Streep in “Out of Africa” (1985).

“Redford has never been so radiantly glamorous,” the critic Pauline Kael wrote in The New Yorker, “as when we saw him through Barbra Streisand’s infatuated eyes.”

He branched into directing in his 40s and won an Academy Award for his first effort, “Ordinary People” (1980), about an upper-middle-class family’s disintegration after a son’s death — a story that reflected the repressed grief and emotional silence in his own family after the death of his mother when he was a teenager. “Ordinary People” won three other Oscars, including for best picture.

Advertisement

His next film as a director, “The Milagro Beanfield War” (1988), a comedic drama about a New Mexican farmer denied water rights by uncaring developers, was a flop. But Mr. Redford stubbornly refused to pursue less esoteric material. Instead, he directed and produced “A River Runs Through It” (1992), a spare period drama about Montana fly fishermen pondering existential questions, and “Quiz Show” (1994), about a notorious 1950s television scandal. “Quiz Show” was nominated for four Oscars, including best picture and best director.

Perhaps Mr. Redford’s greatest cultural impact was as a make-it-up-as-he-went independent film impresario. In 1981, he founded the Sundance Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to cultivating fresh cinematic voices. He took over a struggling film festival in Utah in 1984 and renamed it after the institute a few years later. (He had been a local since 1961, having spent some of his early earnings as an actor on two acres of land in Provo Canyon. He often said he liked Utah because it gave him a sense of peace and was the antithesis of Hollywood superficiality.)

The Sundance Film Festival, in Park City, became a global showcase and freewheeling marketplace for American films made outside the Hollywood system. With heat generated by the discovery of talents like Steven Soderbergh, who unveiled his “Sex, Lies and Videotape” at the festival in 1989, Sundance became synonymous with the creative cutting edge.

The directors Quentin Tarantino, James Wan, Darren Aronofsky, Nicole Holofcener, David O. Russell, Ryan Coogler, Robert Rodriguez, Chloé Zhao and Ava DuVernay were nurtured by Sundance early in their careers. Sundance also grew into one of the world’s top showcases for documentaries, in particular those focused on progressive topics like reproductive rights, L.G.B.T.Q. issues and climate change.

Mr. Redford complained bitterly about the commercial whirlwind the festival created as it grew to more than 85,000 attendees in 2025 from a few hundred in the early 1980s.

Advertisement

“I want the ambush marketers — the vodka brands and the gift-bag people and the Paris Hiltons — to go away forever,” Mr. Redford told a reporter during the 2012 festival, as he trudged in snow boots to a screening, a young assistant behind him struggling to keep up. “They have nothing to do with what’s going on here!”

Preferring life on his secluded Utah ranch, Mr. Redford created the image of a reluctant star. His Hollywood career, he insisted with characteristic orneriness, was incidental to his real concerns, one of which was the environment. In many ways, he created the actor-as-environmentalist archetype that stars like Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo would adopt.

Mr. Redford did not like to be called an activist, a label he found too severe. But an activist he was.

In 1970, he successfully campaigned against a six-lane highway that was proposed in a Utah canyon (where one year he received eight tickets for speeding, rounding the curves in a Porsche Carrera).

For five decades, Mr. Redford was a trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council. In 1976, he used his clout to help block the construction of a coal-fired power plant in Utah that had been championed by business leaders as a crucial source of jobs. His campaign against the plant included a 36-page photo spread in National Geographic magazine featuring himself on horseback on the scenic Kaiparowits plateau, where construction was to begin. His efforts sparked a backlash — he was called a liberal carpetbagger — and residents of one Utah town burned him in effigy.

Advertisement

From time to time, people with similar political priorities encouraged him to run for office. He brushed such chatter aside, having become disillusioned with government in the late 1970s, when he was elected commissioner of the Provo Canyon sewer district. (He had sought the office in an effort to protect the Provo Canyon area near his home from development and pollution. But he quickly encountered bureaucracy, which reinforced his belief that independent activism and storytelling through film were more effective tools for change.)

“I was born with a hard eye,” he told The Hollywood Reporter in 2014. “The way I saw things, I would see what was wrong. I could see what could be better. I developed kind of a dark view of life, looking at my own country.”

A California Youth

Charles Robert Redford Jr. was born on Aug. 18, 1936, in Santa Monica, Calif. His parents, Charles Redford and Martha Hart, married three months later. (Early in his career, 20th Century Fox publicists officially placed Mr. Redford’s birth in 1937, a falsehood that was often repeated over the years.)

After working as a milkman, Mr. Redford’s mercurial father became an accountant and was eventually employed by Standard Oil of California. His mother died in 1955, when Mr. Redford was in his late teens; the cause was a blood disorder associated with the birth of twin girls, who had lived only a short while, leaving Mr. Redford an only child. Her death left him angry and disillusioned.

“I’d had religion pushed on me since I was a kid,” he later told a biographer, Michael Feeney Callan. “But after Mom died, I felt betrayed by God.”

Later in life, Mr. Redford, in dozens of interviews, told and retold the story of his California youth. It was an oral history in which the details sometimes shifted. He liked to cast himself in memory as a juvenile delinquent, sometimes mentioning gang fights, other times hubcap stealing and nights spent in jail. “There was great fear I was going to end up a bum,” he told TV Guide in 2002. He found Van Nuys, the Los Angeles neighborhood where the family lived, to be unbearably conformist and dull — revealing a rebellious nature that never left him.

Advertisement

Little was ever mentioned of early show business connections that suggested the possibility of a screen future, although he spoke about getting laughed off the Warner Bros. lot at age 15 when asking for stunt work.

In fact, at schools in west Los Angeles, he kept company with children of the screenwriter Robert Rossen (“The Hustler”), the actor Zachary Scott (“Mildred Pierce”) and the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer president Dore Schary. In 1959, Mr. Schary produced a Broadway play, “The Highest Tree,” in which Mr. Redford had one of his first stage roles.

He had made his Broadway debut earlier that year in “Tall Story,” in which he had a one-line part. His most successful Broadway appearance was as an uptight lawyer in the Neil Simon comedy about newlyweds, “Barefoot in the Park,” in 1963, directed by Mike Nichols and co-starring Elizabeth Ashley as a free-spirited wife.

After high school, Mr. Redford attended the University of Colorado on a baseball scholarship, but he soon dropped out, having chafed at too much “bureaucracy,” as he put it. He had also developed a fondness for all-night beer parties.

For more than a year he bounced around Europe, where he studied art at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, aspired to paint, and — working through what he later described as profound depression — sold sidewalk sketches for pocket cash. (He had been a talented illustrator since high school.)

Advertisement

Back in Los Angeles, he did oil-field work and met several Mormon students who were sent to proselytize after their first year at Brigham Young University in Utah. He dated one of them, Lola Van Wagenen, and married her in 1958.

The couple would become rooted in Utah. “It’s not trying to pretend to be something it’s not,” he told Rocky Mountain magazine in 1978, comparing Utah with Los Angeles, which he called phony and superficial. “It doesn’t invite you in and then kick you in the shins.”

Film critics loved to kick Mr. Redford.

In 1974, his performance as Jay Gatsby in “The Great Gatsby” received near-universal disdain, with Ms. Kael writing that Mr. Redford “couldn’t transcend his immaculate self-absorption.” Robert Mazzocco, a critic for The New York Review of Books, wrote that Mr. Redford “has the emotions of a telephone recording from Con Ed.”

While the movie was a box-office hit, the response was so harsh that The New York Times weighed in with an article bearing the headline “Why Are They Being So Mean to ‘The Great Gatsby’?” The writer, Foster Hirsch, then enumerated the reasons. “Gatsby is one of the great losers in American literature,” the article said. “Does Redford, with his male model looks, answer such a description?”

Box-Office Gold